2.4 Utilitarianism: The Greatest Good for the Greatest Number

2.4 Utilitarianism: The Greatest Good for the Greatest Number

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Identify the principle elements of Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarianism

Distinguish John Stuart Mill’s modification of utilitarianism from Bentham’s original formulation of it

Evaluate the role of utilitarianism in contemporary business

Although the ultimate aim of Aristotelian virtue ethics was eudaimonia, later philosophers began to question this notion of happiness. If happiness consists of leading the good life, what is good? More importantly, who decides what is good? Jeremy Bentham (1748–1842), a progressive British philosopher and jurist of the Enlightenment period, advocated for the rights of women, freedom of expression, the abolition of slavery and of the death penalty, and the decriminalization of homosexuality. He believed that the concept of good could be reduced to one simple instinct: the search for pleasure and the avoidance of pain. All human behavior could be explained by reference to this basic instinct, which Bentham saw as the key to unlocking the workings of the human mind. He created an ethical system based on it, called utilitarianism. Bentham’s protégé, John Stuart Mill (1806–1873), refined Bentham’s system by expanding it to include human rights. In so doing, Mill reworked Bentham’s utilitarianism in some significant ways. In this section we look at both systems.

Maximizing Utility

During Bentham’s lifetime, revolutions occurred in the American colonies and in France, producing the Bill of Rights and the Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme (Declaration of the Rights of Man), both of which were based on liberty, equality, and self-determination. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published The Communist Manifesto in 1848. Revolutionary movements broke out that year in France, Italy, Austria, Poland, and elsewhere.37 In addition, the Industrial Revolution transformed Great Britain and eventually the rest of Europe from an agrarian (farm-based) society into an industrial one, in which steam and coal increased manufacturing production dramatically, changing the nature of work, property ownership, and family. This period also included advances in chemistry, astronomy, navigation, human anatomy, and immunology, among other sciences.

Given this historical context, it is understandable that Bentham used reason and science to explain human behavior. His ethical system was an attempt to quantify happiness and the good so they would meet the conditions of the scientific method. Ethics had to be empirical, quantifiable, verifiable, and reproducible across time and space. Just as science was beginning to understand the workings of cause and effect in the body, so ethics would explain the causal relationships of the mind. Bentham rejected religious authority and wrote a rebuttal to the Declaration of Independence in which he railed against natural rights as “rhetorical nonsense, nonsense upon stilts.”38 Instead, the fundamental unit of human action for him was utility—solid, certain, and factual.

What is utility? Bentham’s fundamental axiom, which underlies utilitarianism, was that all social morals and government legislation should aim for producing the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. Utilitarianism, therefore, emphasizes the consequences or ultimate purpose of an act rather than the character of the actor, the actor’s motivation, or the particular circumstances surrounding the act. It has these characteristics: (1) universality, because it applies to all acts of human behavior, even those that appear to be done from altruistic motives; (2) objectivity, meaning it operates beyond individual thought, desire, and perspective; (3) rationality, because it is not based in metaphysics or theology; and (4) quantifiability in its reliance on utility.39

Ethics Across Time and Cultures

The “Auto-Icon”

In the spirit of utilitarianism, Jeremy Bentham made a seemingly bizarre request concerning the disposition of his body after his death. He generously donated half his estate to London University, a public university open to all and offering a secular curriculum, unusual for the times. (It later became University College London.) Bentham also stipulated that his body be preserved for medical instruction (Figure 2.7) and later placed on display in what he called an “auto-icon,” or self-image. The university agreed, and Bentham’s body has been on display ever since. Bentham wanted to show the importance of donating one’s remains to medical science in what was also perhaps his last act of defiance against convention. Critics insist he was merely eccentric.

Figure 2.7 At his request, Jeremy Bentham’s corpse was laid out for public dissection, as depicted here by H.H. Pickersgill in 1832. Today, his body is on display as an “auto-icon” at University College, London, a university he endowed with about half his estate. His preserved head is also kept at the college, separate from the rest of the body.) (credit: “Mortal Remains of Jeremy Bentham, 1832” by Weld Taylor and H. H. Pickersgill/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

Critical Thinking

What do you think of Bentham’s final request? Is it the act of an eccentric or of someone deeply committed to the truth and courageous enough to act on his beliefs?

Do you believe it makes sense to continue to honor Bentham’s request today? Why is it honored? Do requests have to make sense? Why or why not?

Bentham was interested in reducing utility to a single index so that units of it could be assigned a numerical and even monetary value, which could then be regulated by law. This utility function measures in “utils” the value of a good, service, or proposed action relative to the utilitarian principle of the greater good, that is, increasing happiness or decreasing pain. Bentham thus created a “hedonic calculus” to measure the utility of proposed actions according to the conditions of intensity, duration, certainty, and the probability that a certain consequence would result.40 He intended utilitarianism to provide a reasoned basis for making judgments of value rather than relying on subjectivity, intuition, or opinion. The implications of such a system on law and public policy were profound and had a direct effect on his work with the British House of Commons, where he was commissioned by the Speaker to decide which bills would come up for debate and vote. Utilitarianism provided a way of determining the total amount of utility or value a proposal would produce relative to the harm or pain that might result for society.

Utilitarianism is a consequentialist theory. In consequentialism, actions are judged solely by their consequences, without regard to character, motivation, or any understanding of good and evil and separate from their capacity to create happiness and pleasure. Thus, in utilitarianism, it is the consequences of our actions that determine whether those actions are right or wrong. In this way, consequentialism differs from Aristotelian and Confucian virtue ethics, which can accommodate a range of outcomes as long as the character of the actor is ennobled by virtue. For Bentham, character had nothing to do with the utility of an action. Everyone sought pleasure and avoided pain regardless of personality or morality. In fact, too much reliance on character might obscure decision-making. Rather than making moral judgments, utilitarianism weighed acts based on their potential to produce the most good (pleasure) for the most people. It judged neither the good nor the people who benefitted. In Bentham’s mind, no longer would humanity depend on inaccurate and outdated moral codes. For him, utilitarianism reflected the reality of human relationships and was enacted in the world through legislative action.

To illustrate the concept of consequentialism, consider the hypothetical story told by Harvard psychologist Fiery Cushman. When a man offends two volatile brothers with an insult, Jon wants to kill him; he shoots but misses. Matt, who intends only to scare the man but kills him by accident, will suffer a more severe penalty than his brother in most countries (including the United States). Applying utilitarian reasoning, can you say which brother bears greater guilt for his behavior? Are you satisfied with this assessment of responsibility? Why or why not?41

Link to Learning

A classic utilitarian dilemma considers an out-of-control streetcar and a switch operator’s array of bad choices. Watch the video on the streetcar thought experiment and consider these questions. How would you go about making the decision about what to do? Is there a right or wrong answer? What values and criteria would you use to make your decision about whom to save?

Synthesizing Rights and Utility

As you might expect, utilitarianism was not without its critics. Thomas Hodgskin (1787–1869) pointed out what he said was the “absurdity” of insisting that “the rights of man are derived from the legislator” and not nature.42 In a similar vein, the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834) accused Bentham of mixing up morality with law.43 Others objected that utilitarianism placed human beings on the same level as animals and turned people into utility functions. There were also complaints that it was mechanistic, antireligious, and too impractical for most people to follow. John Stuart Mill sought to answer these objections on behalf of his mentor but then offered a synthesis of his own that brought natural rights together with utility, creating a new kind of utilitarianism, one that would eventually serve to underpin neoclassical economic principles.44

Mill’s father, James, was a contemporary and associate of Bentham’s who made sure his son was tutored in a rigorous curriculum. According to Mill, at an early age he learned enough Greek and Latin to read the historians Herodotus and Tacitus in their original languages.45 His studies also included algebra, Euclidean geometry, economics, logic, and calculus.46 His father wanted him to assume a leadership position in Bentham’s political movement, known as the Philosophical Radicals.47 Unfortunately, the intensity and duration of Mill’s schooling—utilitarian conditions of education—were so extreme that he suffered a nervous breakdown at the age of twenty years. The experience left him dissatisfied with Bentham’s philosophy of utility and social reform. As an alternative, Mill turned to Romanticism and poets like Coleridge and Johann Wolfgang Goethe (1749–1832).48 What he ended up with, however, was not a rejection of utilitarianism but a synthesis of utility and human rights.

Why rights? No doubt, Mill’s early life and formation had a great deal to do with his championing of individual freedom. He believed the effort to achieve utility was unjustified if it coerced people into doing things they did not want to do. Likewise, the appeal to science as the arbiter of truth would prove just as futile, he believed, if it did not temper facts with compassion. “Human nature is not a machine to be built after a model, and set to do exactly the work prescribed for it, but a tree, which requires to grow and develop itself on all sides, according to the tendency of the inward forces which make it a living thing,” he wrote.49 Mill was interested in humanizing Bentham’s system by ensuring that everyone’s rights were protected, particularly the minority’s, not because rights were God given but because that was the most direct path to truth. Therefore, he introduced the harm principle, which states that the “only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant.” 50

To be sure, there are limitations to Mill’s version of utilitarianism, just as there were with the original. For one, there has never been a satisfactory definition of “harm,” and what one person finds harmful another may find beneficial. For Mill, harm was defined as the set back of one’s interests. Thus, harm was defined relative to an individual’s interests. But what role, if any, should society play in defining what is harmful or in determining who is harmed by someone’s actions? For instance, is society culpable for not intervening in cases of suicide, euthanasia, and other self-destructive activities such as drug addiction? These issues have become part of the public debate in recent years and most likely will continue to be as such actions are considered in a larger social context. We may also define intervention and coercion differently depending on where we fall on the political spectrum.

Considering the social implications of an individual action highlights another limitation of utilitarianism, and one that perhaps makes more sense to us than it would to Bentham and Mill, namely, that it makes no provision for emotional or cognitive harm. If the harm is not measurable in physical terms, then it lacks significance. For example, if a reckless driver today irresponsibly exceeds the speed limit, crashes into a concrete abutment, and kills himself while totaling his vehicle (which he owns), utilitarianism would hold that in the absence of physical harm to others, no one suffers except the driver. We may not arrive at the same conclusion. Instead, we might hold that the driver’s survivors and friends, along with society as a whole, have suffered a loss. Arguably, all of us are diminished by the recklessness of his act.

Link to Learning

Watch this video for a summary of utilitarian principles along with a literary example of a central problem of utility and an explanation of John Stuart Mill’s utilitarianism.

The Role of Utilitarianism in Contemporary Business

Utilitarianism is used frequently when business leaders make critical decisions about things like expansion, store closings, hiring, and layoffs. They do not necessarily refer to a “utilitarian calculus,” but whenever they take stock of what is to be gained and what might be lost in any significant decision (e.g., in a cost-benefit analysis), they make a utilitarian determination. At the same time, one might argue that a simple cost-benefits analysis is not a utilitarian calculus unless it includes consideration of all stakeholders and a full accounting of externalities, worker preferences, potentially coercive actions related to customers, or community and environmental effects.

As a practical way of measuring value, Bentham’s system also plays a role in risk management. The utility function, or the potential for benefit or loss, can be translated into decision-making, risk assessment, and strategic planning. Together with data analytics, market evaluations, and financial projections, the utility function can provide managers with a tool for measuring the viability of prospective projects. It may even give them an opportunity to explore objections about the mechanistic and impractical nature of utilitarianism, especially from a customer perspective.

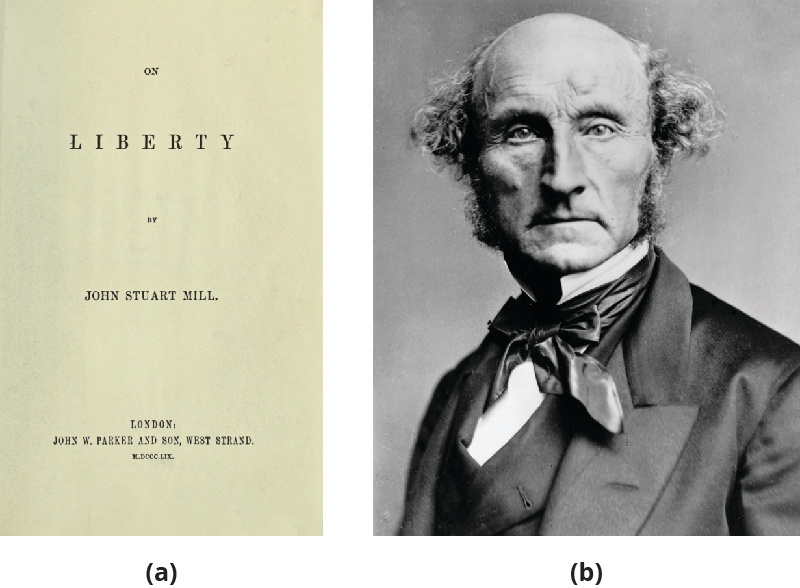

Utilitarianism could motivate individuals within the organization to take initiative, become more responsible, and act in ways that enhance the organization’s reputation rather than tarnish it. Mill’s On Liberty (Figure 2.8), a short treatment of political freedoms in tension with the power of the state, underscored the importance of expression and free speech, which Mill saw not as one right among many but as the foundational right, reflective of human nature, from which all others rights derive their meaning. And therein lay the greatest utility for society and business. For Mill, the path to utility led through truth, and the main way of arriving at truth was through a deliberative process that encouraged individual expression and the clash of ideas.

Figure 2.8 In On Liberty (1859) (a), John Stuart Mill (b) combined utility with human rights. He emphasized the importance of free speech for correcting error and creating value for the individual and society. (credit a: modification of “On Liberty (first edition title page via facsimile)” by “Yodin”/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain; credit b: modification of “John Stuart Mill by London Stereoscopic Company, c1870” by “Scewing”/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

As for Mill’s harm principle, the first question in trying to arrive at a business decision might be, does this action harm others? If the answer is yes, we must make a utilitarian calculation to decide whether there is still a greater good for the greatest number. Then we must ask, who are the others we must consider? All stakeholders? Only shareholders? What does harm entail, and who decides whether a proposed action might be harmful? This was the reason science and debate were so important to Mill, because the determination could not be left to public opinion or intuition. That was how tyranny started. By introducing deliberation, Mill was able to balance utility with freedom, which was a necessary condition for utility.

Where Bentham looked to numerical formulas for determining value, relying on the objectivity of numbers, Mill sought value in reason and in the power of language to clarify where truth lies. The lesson for contemporary business, especially with the rise of big data, is that we need both numbers and reasoned principles. If we apply the Aristotelian and Confucian rule of the mean, we see that balance of responsibility and profitability makes the difference between sound business practices and poor ones.