3 Chapter 3 POWER AND RESISTANCE: Integrity and Religion

Chapter 3

POWER AND RESISTANCE

Integrity and Religion

Learning Objectives

Guiding question: What drives humans to seek power, and how do they establish avenues for securing power, both individually and collectively, in their lives?

-

- Offer theories of drives humans to seek power, and how do they establish avenues for securing power, both individually and collectively, in their lives.

- Apply the understanding of the elements of power to concrete examples found in human history and art.

Stop and Think:

- What needs do you think religion fills in human societies?

- Do you think there is any belief or idea that is present in most religions?

- Can you think of ways people might use religion to oppress or exploit others?

- How would you define religion?

MARTIN LUTHER AND THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION

In this chapter, you will be introduced to the ethical and spiritual questions of the time that still have relevance today. In order to gain a fuller understanding of the moment artistically, it is necessary to have a familiarity with the role of Christianity throughout Europe at the time and the fractious nature of the moment.

We will start with a look at the differentiation of Christianity as a result of the Protestant Reformation. Prior to this point, there was only one Christian church, which we now know as the Roman Catholic Church–in fact, “Catholic” means “universal”–but as a result of the accumulation of power by the Church, Martin Luther led a movement demanding reform. Among abuses he identified were the selling of indulgences, which meant that you could pay the Church to speed your soul to Heaven upon your death. For a deeper understanding of the scope of the power of the Church leading to this call for reform, this video will set the stage for you:

In October 1517, about 10 years after he had been ordained to the priesthood, Martin Luther is said to have posted his 95 Theses to the door of the All Saints Church in Wittenberg. Though that dramatic event itself is disputed by historians, the document itself, originally entitled “Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences” is not. In it, Martin Luther posits questions for discussion in a formal and academic setting regarding themes from the wealth of the pope to the mechanisms of corruption within the Church doctrine itself. Within a few weeks of its completion, the document was translated from Latin into vernacular languages like German and Italian and spread quickly throughout Europe. Though Luther himself advocated for a thoughtful and intellectual consideration of the practices of the Church, others would take his message in a more violent and radical direction, encouraging peasant revolts and general social upheaval. Martin Luther disavowed these practices and demonstrated that these violent acts were not only unlawful but in contradiction to the very principles of Christianity.

Image 3.1 Portrait of young Martin Luther.

As is common with historical figures, some of Martin Luther’s thoughts and writings are problematic to the modern reader. He wrote extensively about Jewish people, portraying them in a negative light and, like his contemporaries, viewed them as responsible for the killing of Jesus Christ. It is thought that his negative regard was in part due to his failure to convert Jewish people in his region to Christianity. As we look at his legacy, it is vital to address and think through the complexities of this and all historical figures.

Watch the following video for a short but thorough introduction to Martin Luther and the effect he had on Christianity and Europe:

As Luther’s ideas spread throughout Europe, they would go on to have an enormous impact politically and socially. In the following video, beginning at minute 4:45, you will be introduced to this religious and political tension in England with Henry VIII and the spread of Protestantism throughout Europe.

This shift in perspective on Christianity brought with it the beginnings of a change of focus in art in Europe. Because so much of the art created during the Renaissance was religious in its content, the Protestants felt that art might take a turn away from the public sphere of churches and concentrate on smaller pieces for individual settings such as private homes. These smaller pieces would shift artistic focus toward inclusion of secular subjects such as the natural world and human endeavors such as work.

Two important artistic products that would emerge during this time were the woodcut and the engraving, the latter of which allowed for replication of a piece of art. This meant that art was more accessible to a broader population and paralleled Protestantism’s focus on the direct engagement of a person to God. A person could now directly engage with art in a private secular setting.

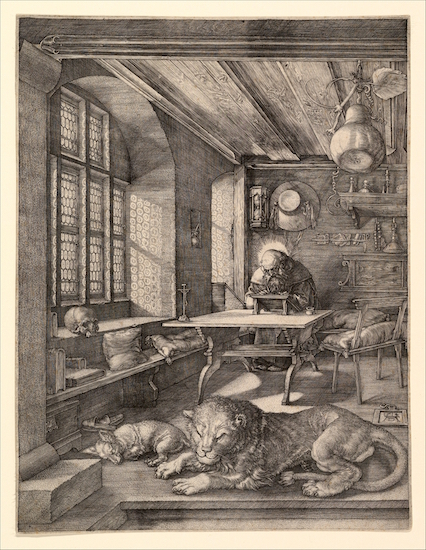

Certainly among the best-known artists of this style was Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) of Nuremberg in modern Germany. Though he did weave elements of classical art into is works, he became a central figure in the secular world not only through his artistic creations but also through his writings on mathematics and the notions of human proportion and perspective. This is not to say that all of his works were secular, in fact toward the end of his life, he created a woodcut of the Last Supper

Image 3.2 Albrecht Dürer, The Last Supper

Among the most famous works Dürer created was his 1514 engraving Melancolia. In this image (below), we see a figure who is listless, head in hand, with an underfed, neglected dog sitting behind her. Of note, the figure is most often referred to with a female pronoun (since the gender of the word “melancholy” is feminine), yet the figure also has androgynous features. Her wings are too small to lift her, and the feeling of inertia and immobility are clear as we see her sitting among various objects scattered halfheartedly around her. It is thought that Dürer here, in his portrayal of the state which we now call depression, has created a version of a self-portrait.

For more on this piece, read the essay below by Dr. Bonnie Noble:

Sunken in despair

Melancholy and artists

To learn more about the process of printmaking, woodcuts, and engraving during this time, watch the following video:

How it’s done: printmaking and engraving

Stop and Think

- How do you think creative arts were transformed by the practices of woodcuts and engravings which allowed for replication of a particular work? Do you think that might have influenced the subjects chosen by artists?

- If an artwork is replicated, such as an engraving, how do you think that affects our perception of an “original”?

- Do you see any connections between the replication of art and the inspiration of Martin Luther for reform of the Church?

- Go back and look at “Melancholia I” again and consider how you think it still reflects the experience of melancholy in our current moment.

THE COUNTER-REFORMATION

The Catholic Church would offer its own vigorous response to Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation. After losing influence and power in vast areas of territory across Europe to Protestantism, the Catholic Church formulated a platform of its own to counter–or push back against–the ideas of the Protestant Reformation. Among these ideas were an increase in the powers of the Pope, establishment of new religious orders (such as the Jesuits, who were focused on education, theology, and missionary work), and even the Inquisition to root out what the Church viewed as heresy among the population. An important element of the Counter-Reformation was the focus on missionary work to retain and expand the influence of the Church outside Europe and the increasing focus on theology among the clergy. Prior to the Protestant Reformation, many priests and clergy suffered from a lack of a standardized catechism (a summary of the doctrine of the Church) and were not able to effectively teach and instruct their flock.

Introduction to the Reformation and Counter-Reformation

THE COUNCIL OF TRENT

•Church offices were no longer able to be sold.

•Bishops, many of whom lived in Rome, had to go back to their diocese, preach regularly, and be active amongst their parishioners.

•Bishops were also to maintain strict celibacy and to build a seminary in every diocese.

•There were no doctrinal changes.

•The Council did set parameters for the uses of art, however.

Music also played a significant role in conveying the message of the gospel and was used as a part of the liturgy. Listen to this piece and note the centrality of the voices of the choir and the restraint of the orchestration. The “Kyrie” (or Kyrie eleison) is a part of the Christian liturgy that means “Lord have mercy”.

THE BAROQUE

Italy pioneered the Baroque period when the artists combined the great painting style of the Renaissance with the emotional drama of the

One of the most persuasive contributors to Baroque art was Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610), who was born in Milan, Italy. Using a process he revolutionized, Caravaggio created illuminated lighting, the stark contrast between the light and dark areas to produce dramatic religious scenes where the human form emerged out of a deep shadow. Tenebrism, with its powerful distinctions of light and dark, became the painting process used for Baroque in Italy.

Scorning the traditional idealized interpretation of religious subjects, Caravaggio took his models from the streets and painted them realistically. In the Crucifixion of Saint Peter below, Caravaggio shows the rising of Saint Peter’s cross, right in front of the viewer. Caravaggio was a master at secularizing religious art by depicting ordinary people, dirt and all.

Image 3.7 Michelangelo Caravaggio. The Crucifixion of Saint Peter depicts an elderly man being nailed to a cross.

Image 3.8 Michelangelo Caravaggio. Calling of Saint Matthew.

The Calling of Saint Mathews illustrates the moment Christ calls on Mathew as they glance across the room at each other, their positions highlighted by a shaft of light. The light appears outside the frame, contrasting the men at the table in light and dark shadows. The harsh use of light illuminates the sections of the painting that Caravaggio felt was important, such as Christ’s hand pointing at Mathew, and then casts the non-essential elements in deep shadows. The dramatic effect is bold, intense, and captures the moment Christ supposedly stated, “Follow me”.

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1653), followed Caravaggio in style and theatrical illumination. Gentileschi was the first woman painter to become famous in her own time, depicting paintings of feminist subjects. Using the chiaroscuro methods from the renaissance and combining them with Caravaggio’s use of light, Gentileschi created Judith and her Maidservant. In most of her paintings, she portrayed the women as the protagonist who is courageous, powerful, and rebellious, and without the common feminine traits of weakness and timorous. In this powerful painting, the two women have just killed Holofernes, and his head is in the basket she carries. Standing triumphant after the decapitation, they know the danger, yet do not show fear. Esther before Ahasuerus follows the same theme, Esther, and the Jewish heroine appears before the king to plead for her people, fainting from the stress of her actions.

Image 3.9 Artemisia Gentileschi Judith and Her Maidservant

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), one of the greatest sculptors of the 17th century and perhaps one of the most impressive architects in Rome, designed sculptures for different parts of Rome’s churches, including Saint Peters. Bernini created a romantic style of sculpture in the

One of Bernini’s most significant accomplishments and most distinguished work is located in Cornaro Chapel, Santa Maria Della Vittoria, Rome. The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa below is the culmination of Bernini’s ability to use architecture, sculpture, and theater set design to create an altarpiece set like a stage performance, constructed of stone.

The stage was set with a reclining Saint Teresa floating on a cloud of stone. Carved out of brilliant white marble, she is in the exact moment right before she is struck with the angel’s dart of divine love. The long-gilded streams of gold behind the saint are lit by a hidden window giving the illusion of light from the heavens.

Bernini created the theatrical experience for all church members by creating ‘opera’ boxes on each side of the saint (9.15). Many members of the Cornaro family can be found in the boxes carved in many different poses, engaged in deep conversation, prayer, or reading a book. The complex arrangement tells a story, reviving Christ’s passion, and inviting the viewer into the scene.

OUTSIDE EUROPE: THE MEXICAN BAROQUE

The Baroque period found its way to Mexico with the Spanish immigrants, and in concert with the indigenous artists, architecture, sculpting, and painting flourished. The wealthiest province of New Spain, Mexico, produced extravagant architecture known as Mexican Churrigueresque (ultra-Baroque), the ornamentation, use of bright, vivid colored tile and gold leaf against the white interior stucco, moved Mexican

Jerónimo de Balbás (1680-1748) was a Mexican architect and sculptor known for his estipite columns shaped as an inverted cone covered with elaborate and ornate decorations. One of the main altars, the Altar of the Kings in the Cattedral Metropolitana, Mexico City’s central cathedral, resembles a gold-plated grotto. Space was divided into sections separated by the unusual columns inset with statues and paintings depicting religious stories. The design and architecture of this altar quickly spread to become the standard in churches around Mexico.

Image 3.16 Altar of the Kings

Image 3.16 Altar of the KingsLorenzo Rodríguez (1704-1774) was another Mexican Baroque architect and the originator of the Churrigueresque style. Rodríguez built a small church next to the cathedral in the ornate baroque style, adding his ideas of complexity and richness of details. The Sagrario Metropolitano (Metropolitan Tabernacle) section (9.22) (the smaller building is seen below to the right of the cathedral) built by Rodríquez displays his zoomorphic reliefs along the main façade, including lions, eagles, anthropologic reliefs as well as the coat of arms of Mexico. Details demonstrate his ability to richly decorate with fruits, floral, and pomegranates representing iconic symbols of the Catholic religion.

Sebastián López de Arreaga (1610-1652) was a Mexican Baroque painter adopting the customary tenebrism and chiaroscuro from the

Cristóbal de Villalpando (1649-1714) was another baroque painter known for his luminous and ornate two-dimensional paintings in churches. Using artificial light sources to illuminate and highlight his message, Villalpando painted with meticulous brushstrokes, adding a touch of drama. The semi-circle of angels, in Lady of Sorrows below, clad in red or gold, provides a startling contrast with the static, central figure dressed in dark clothing, symbolizing her sorrow. Villalpando illuminates the faces from multiple directions illustrating his use of light from unknown places.

Write a 500-word essay on one of the following topics:

- Much of the work of Renaissance artists focused on themes and figures in Christianity. How do you think that has influenced study of the Renaissance outside the modern Christian world?

- After thinking about the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation in response, do you think that change can occur without pressure from an outside/opposing source? What is it that you think drives change in institutions like religion, education, government?

- Consider the theme of order versus confusion. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, in the Book of Genesis, God is said to have created the world with order and purpose. How do you think–or do you think–that orderliness has been perceived to be more “holy,” both in the Renaissance and in our current day? Why do you think that so many religions have ritual cleansing as part of their structures? (During a Catholic Mass, the washing of the priest’s hands, for example, or before praying, Muslims are to perform Wudu, a washing of faces, hands, arms, and feet.)