2 Chapter 2 METAMORPHOSIS: The Arts

CHAPTER TWO

METAMORPHOSIS: THE ARTS

Learning Objectives

Guiding question: How is change represented in Renaissance art?

- Describe elements of change as represented in the works of the artists of the Italian Renaissance.

- Apply the role of science and scientific inquiry in Renaissance art.

Now that we’re thinking about the enormous restructuring of life during the early Renaissance, let’s turn again and in further depth to identifying ways in which those metamorphoses are visible in art. During this period, artists will serve patrons and in so doing bring continuity and form to artistic expression but also bring limitations and exclusions.

As we begin, consider the following questions:

- How do you think the system of patronage influenced the style of art that was created during the Renaissance?

- Think of a few examples of art that you would say reflect our current moment. How would those artworks help someone in the year 2500 understand our current culture?

- What life circumstances do you think are necessary for someone to create art?

- Whom do you think is excluded from seeing or creating art today?

- Why do you think protest groups often act upon great works of art to help further their cause? (Tomato soup on Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” and mashed potatoes on Monet’s “Grainstack” in October 2022)

First, to set the stage, take a quick look at the phenomenological experience of color and how it affects our engagement with art:

One striking distinction between the Renaissance and our current moment is the element of creative expression. If you are a writer, artist, or musician or have friends who are, you’ll know that our culture often presents artistic output as the creative release of the artist’s feelings, emotions, or sensibility about the world. Often we hear writers and artists say that their creations allow them to express themselves–an idea which did not occupy the same a place in the art of the Renaissance. Our modern luxury of art for the sake of personal expression was not available to most ordinary–even if talented–people during this time. Consider the amount of free time required to create a drawing, a painting, a song, or a sculpture. Only the very few were afforded the luxury of free time in the 15th Century. An additional and prohibitive consideration, of course, is the cost of materials. You and I might run to our local art supply store and be able to purchase paint, brushes, paper, drawing instruments, even sculpting materials at a very low cost. During the Renaissance, art materials were not widely available, nor were they affordable for any but the wealthiest in society.

Additionally, most ordinary people during this era were not in a position to visit a museum as we do today or to access most art created at the time since it was usually owned by a private person or family and not viewable to the public. One exception is public art, that is, outdoor sculptures and architecture. As you go on to regard examples throughout this textbook, ask yourself whether you as a member of the general public would have had access to the artworks. Chances are very few of us would have been born into the handful of powerful families, so the way we would engage with art would necessarily be limited to that in the public sphere.

In fact, in one example of public art which we might now consider “graffiti,” Michelangelo himself may have carved a small profile of a man into a building in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. Though debated among scholars, it is indeed intriguing to consider this publicly available portrait as an example of public art.

So as we go forth and begin to further explore the famous masterpieces from the Renaissance, let’s keep in mind the economic and social conditions which made their creation possible, the advantages that artists with patronage enjoyed, and the importance of public art to the entire population.

How all this art became possible.

Part 1: Medieval to Renaissance

We begin by considering the production and consumption of art from the Crusades through to the period of the Catholic Reformation. The focus is on art in medieval and Renaissance Christendom, but this does not imply that Europe was insular during this period. The period witnessed the slow erosion of the crusader states in the Holy Land, finally relinquished in 1291, and of the Greek Byzantine world until Constantinople fell to the Ottomans in 1453. Columbus made his voyage to the Americas in 1492. Medieval Christendom was well aware of its neighbors. Trade, diplomacy, and conquest connected Christendom to the wider world, which in turn had an impact on art.

Any notion of the humble medieval artist oblivious to anything beyond his own immediate environment must be dispelled. Artists and patrons were well aware of artistic developments in other countries. Artists traveled both within and between countries and on occasion even between continents. Such mobility was facilitated by the network of European courts, which were instrumental in the rapid spread of Italian Renaissance art. Europe-wide frameworks of philosophical and theological thought, reaching back to antiquity and governing religious art, applied – albeit with regional variations – throughout Europe.

Art, Visual Culture, and Skill

The term ‘visual culture’ is used here in preference to ‘art’ for the fundamental reason that the arts before 1600 were wide-ranging, including media today that we might deem within the realm of craft and not fine art. The Latin word ‘ars’ signified skilled work; it did not mean art as we might understand it today, but a craft activity demanding a high level of technical ability, including tapestry weaving, goldsmith’s work, and embroidery. Literary statements of what constituted the arts during the medieval period are rare, particularly in northern Europe, but proliferate in the Renaissance. Giorgio Vasari (1511–74), the biographer of Italian artists, claimed in his famous book Le vite de’ più eccelenti pittori, scultori e architettori (Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects; first edition 1550 and revised 1568) that the architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) was initially apprenticed to a goldsmith ‘to the end that he might learn design’ (Vasari, 1996 [1568], vol. 1, p. 326). According to Vasari, several other Italian Renaissance artists are supposed to have trained initially as goldsmiths, including the sculptors Ghiberti (1378–1455) and Verrocchio (1435–88), and the painters Botticelli (c.1445–1510) and Ghirlandaio (1448/49–94). The design skills necessary for goldsmiths’ work were evidently a good foundation for future artistic success.

Medieval and Renaissance Visual Culture

The term ‘visual culture’ is also used for a second reason that is less to do with definition than with method. Including the various arts under the umbrella of ‘visual culture’ implies their inseparability from the visual rhetoric of power on the one hand, and the material culture of a society on the other. Before 1500 art was primarily part of the persuasive power and cultural identity of the church, ruler, city, institution, or the wealthy patron commissioning the artwork. In this sense, art might be considered alongside ceremonies, for example, as strategies conveying social meaning or magnificence, or as a demonstration of wealth and power by the patron commissioning the artwork to be made.

In later centuries art evolves into purely an aesthetic entity, prompting scrutiny for its own sake alone. The intent of the varied forms of art produced during the medieval and Renaissance period lie outside this definition. Objects were made that invited attentive scrutiny for their ingenuity in design, while at the same time fulfilling a variety of functions. No one in medieval times would have bothered to commission works of art unless they could assume that their contemporaries would understand and perhaps be influenced by their communicative power. For example, the wealthy lavished money on rich artifacts or dynastic portraits in part because these objects were a way of communicating their exclusiveness and social power to their contemporaries.

Artistic Quality

The fact that a work of art had a function did not mean that artistic quality was a matter of indifference. Some artists’ guilds required candidates to submit a ‘masterpiece’ for examination by the guild in order to win the status of master. Those scrutinizing the masterpieces must have had a clear idea of the criteria of quality they were hoping for, even if these criteria were never set down in writing. The careful selection of artists even from far-flung locations, and the preference for one practitioner above another, shows that patrons too were quite capable of discriminating on the basis of artistic prowess. A work of art during the medieval and Renaissance period was expected to be of high quality as well as purposeful.

Artists and Patrons

Famously, in 1516, the renowned Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was invited to the French court of Francis I (ruled 1515–47), perhaps not so much for the work that he might produce at what was then an advanced age, as out of admiration and presumably for the prestige that the presence of such a renowned figure might endow on the French court. The advancement of artistic status is often associated with princely employment. Patron is the term for the person or entity who commissions or hires the artist to create artwork. Given the example of Leonardo da Vinci, this appears to make sense. Maintained on a salary, a court artist was no longer a jobbing craftsman constantly on the lookout for work. Potentially, at least, he had access to projects demanding inventiveness and conferring honor, and time to lavish on his art and on study. Equally, however, court artists might be required to undertake mundane and routine work which they could not very well refuse. Court salaries were also often in arrears or not paid at all. In the same letter in which Leone Leoni described Charles V chatting with him for two to three hours at a time, he complains of his poverty, while carefully qualifying the complaint by claiming he serves the emperor for honor and cares for studying not moneymaking. The lot of the court artist might appear to fulfill aspirations for artistic status, but it certainly had its drawbacks.

Patterns of Artistic Employment: Workshop, Guild, and Court Employment

The pattern of artistic employment in the medieval period and the Renaissance varied. Traditionally, craftsmen working on great churches would be employed in workshops on site, albeit often for some length of time; during the course of their career, such craftsmen might move several times from one project to another. Many other artists moved around in search of new opportunities of employment, even to the extent of accompanying a crusade. Artists working for European courts might travel extensively as well, not just within a country but from country to country and court to court: El Greco (1541–1614) moved between three different countries before finding employment not at the royal court in Spain but in the city of Toledo.

A fixed artist’s workshop depended not only on local institutional and individual patronage, but often also on the willingness of clients from further afield to come to the artist rather than the artist traveling to work for clients.

A guild served three main functions: promoting the social welfare of its members, maintaining the quality of its products and protecting its members from competition. This usually meant defining quite carefully the materials and tools that a guild member was allowed to use to prevent activities that infringed the privileges of other guilds and for which they had not been trained, for example a carpenter producing wood sculpture.

It is the protection from competition that art historians have seen as eliminating artistic freedom, but it is worth pausing to wonder whether this view owes more to modern free-market economics than to the realities of fifteenth-century craft practices. In practice, it meant that domestic craftsmen enjoyed preferential membership rates, but in many artistic centers foreign craftsmen were clearly also welcomed so long as their work reflected favorably on the reputation of the guild.

As the debate about artistic status grew, the real disadvantage of the guild system for artists was not so much lack of freedom or profitability or even status so much as the connotations of manual craft attached to the guild system of apprenticeship as opposed to the ‘liberal’ training offered by the art academies.

MANNERISM

Mannerism is a difficult term to define but it is an enduring presence or style of art during the Renaissance. Sometimes defined as a “stylish style,” Mannerist works reflect an intentional artificiality, whether in terms of proportions, arrangement, or background, as well as an effort on the part of the artist to elicit an emotional response from the viewer of the work. Though originally used as a pejorative descriptor, “Mannerism” now is commonly used to describe European art throughout the 16th century.

For further definition, let’s read an excerpt from “Mannerism, an introduction” by Dr. Heather Graham and Dr. Laura Kilroy-Ewbank:

Towards a definition of mannerism

.

Here’s a quick self-assessment quiz about Mannerism:

Now that we’re a little more familiar, let’s look at a comprehensive review of the movement with more paintings but also examples from sculpture:

Stop and Think

- How would you connect Mannerism to today’s photos on Instagram? (We don’t have a term “Instagram face” for nothing, right?) If you had to describe today’s “stylish style,” what elements would you think were most important?

- How do you think Mannerism reflected the prevailing cultural ideas at the time? Can you think of any type of art that would serve the same function today?

MICHELANGELO AND DA VINCI

Surely the two most famous visual artists of the time were Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. Both artists created various types of visual arts, from painting to sculpture to drawing, but both also branched out beyond those arts. Michelangelo was also an architect and poet while da Vinci was an inventor, a scientist, and an engineer. The now-outdated term “Renaissance man,” which connotes a person whose knowledge base spans multiple disciplines of study, referred to these artists who were well-versed in areas of the sciences and arts both.

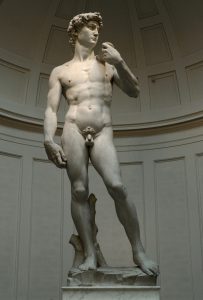

MICHELANGELO

Michelangelo, whose full name was Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarotti Simoni, (1475-1564) is thought to be the first artist recognized as a genius by his contemporaries and was in fact referred to as “the divine”. Though he is most remembered for his visual works such as the Sistine Chapel, he also wrote hundreds of poems. Below is a compilation of his sonnets translated into rhyming English:

Michelangelo wrote sonnets too!

Image 2.3 Michelangelo, David. Photo by Alex Ghizila on Unsplash

To gain a fuller understanding of the scope of Michelangelo’s life and works, watch the video below:

The Complexity of Michelangelo and his Legacy:

https://fod-infobase-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/p_ViewVideo.aspx?xtid=59658&tScript=0

And for a deeper dive into some of his most famous individual works, follow this link:

More on Michelangelo and Florence

LEONARDO DA VINCI

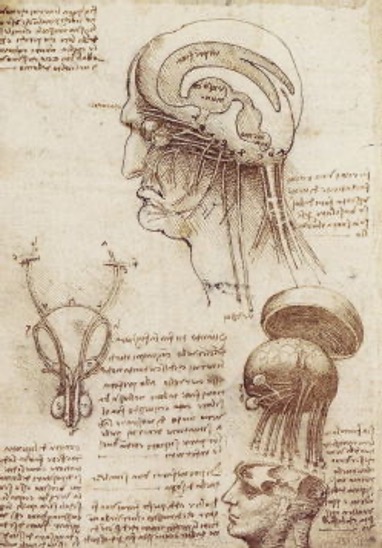

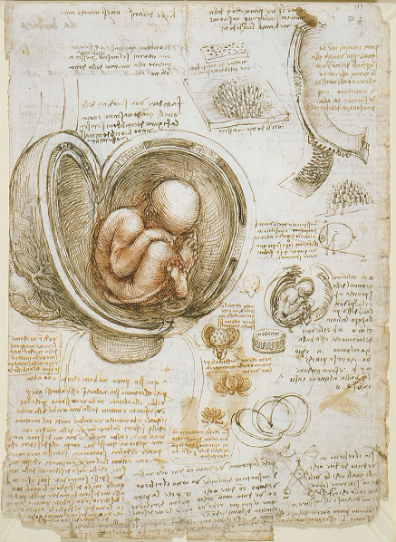

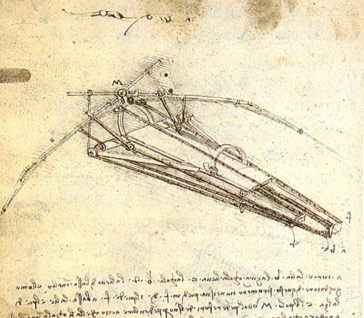

Now when it comes to Leonardo da Vinci, in addition to his visual art, let’s devote at least a few moments to contemplating some of his inventions, many of which will sound quite familiar to today’s reader: an armored car, a deep-sea diving suit, a parachute, a glider, and a prototype for a helicopter. Additionally, his vivid interest in representation of the human body in art led him to dissect an estimated 30 cadavers, noting the musculoskeletal system, the cardiovascular system, the digestive tract, the female reproductive organs. This interest in anatomy allowed da Vinci to represent the human form with precise detail. The excerpt below comes from this comprehensive look at the art of the Renaissance found at

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (aka Leonardo da Vinci) (1452-1519)

is one of the Renaissance’s most famous painters, architect, scientist, mathematician, astronomer, botanist, writer, engineer, inventor, musician, and sculptor. Leonardo Da Vinci was born into a prominent Tuscan family and moved to Florence at the age of seventeen to begin his art career. Leonardo joined the artist guild and soon flourished in the intellectual atmosphere. Da Vinci bounced around from patron to patron, painting, drawing, and designing. He drew anatomy from stolen corpses, learning how the (8.19) body and brain worked and drawing elaborately detailed pictures of the elements of the human body, including a fetus in the womb (8.20). Leonardo had an insatiable curiosity for knowledge, which led to thousands of drawings in the sciences.

Leonardo was born April 15, 1452 in Vinci in Tuscany, the illegitimate child of Sir Piero da Vinci, a Florentine notary, and

a peasant girl named Caterina. He spent his boyhood in a small village with his mother and stepfather and at the age of five

his real father took him because his legitimate marriage had proven childless and he wanted an heir. Leonardo entered

Verrocchio’s workshop as an apprentice in Florence at an early age. Verrocchio was skilled in painting, sculpting and goldsmithing, and Leonardo became a member of the guild at age 20. He had no formal education in math or language, which

often frustrated him because he could not understand the classic languages of the past. Leonardo was said to be a fancy

dresser. He had a beautiful singing voice, a sense of humor which included dirty jokes, was skilled in horsemanship, and

sought court appointments. He had no desire to be the head of a workshop because he wanted to be free to move when he

wanted to.

During this time it was against church doctrine to dissect the human body so Leonardo went to the hospitals with a

priest and got permission to dissect and draw dead bodies. This helped him understand how bones and tendons and organs

were connected, and allowed him to be more precise when he drew and painted. Leonardo “did practical work in anatomy

on the dissection table in Milan, then at hospitals in Florence and Rome, and in Pavia, where he collaborated with the

physician-anatomist Marcantonio della Torre. People complained about Leonardo, that his drawings were doodles, that he was distracted, and that he could not finish his work. Often he did not finish his projects because he became bored or because a better opportunity presented itself. For Leonardo, the idea was important, the completion was secondary.

Leonardo’s drawings reveal an interest in botany, geology, zoology, hydraulics, military engineering, animals, anatomy,

mechanics, perspective, light, color, and musical notation. He drew models of such things as three speed transmission

gears, pile drivers, water turbines, lathes, printing presses, revolving stages, the machine gun, the helicopter, tanks, a

conical valve to regulate the flow of water through a pipe. He drew a double-decker city, invented landscapes with clouds,

trains, sunny lakes, and mountains. He kept his notebooks for over thirty years, but there is not a single reference to his

personal feelings. He left us his laundry lists, doodles, plants, flowers, and animals, but nothing to tell us how he felt. He

believed that everything in nature was worth looking at, and it was his ambition to discover the laws of nature and how

they worked. His drawings were a means to an end, not an end in themselves. His notebooks were written in mirror script,

which is difficult to read and use.

Image 2.4 da Vinci, Drawing of Brain physiology

Image 2.5 da Vinci, Drawing of Fetus in the womb

Leonardo Da Vinci left a large body of drawings of his scientific concepts for us to study. One can imagine Leonardo observing the natural world, looking at every detail, and thinking about every line. Before he even lifted a paintbrush, Leonardo completed a series of drawings, setting the stage for the actual painting. Leonardo only painted nineteen pictures in his lifetime; however, he was a prolific illustrator and writer. His Italian script was written backward and can be easily read in front of a mirror.

Image 2.6 da Vinci, Drawing of Flying Machine

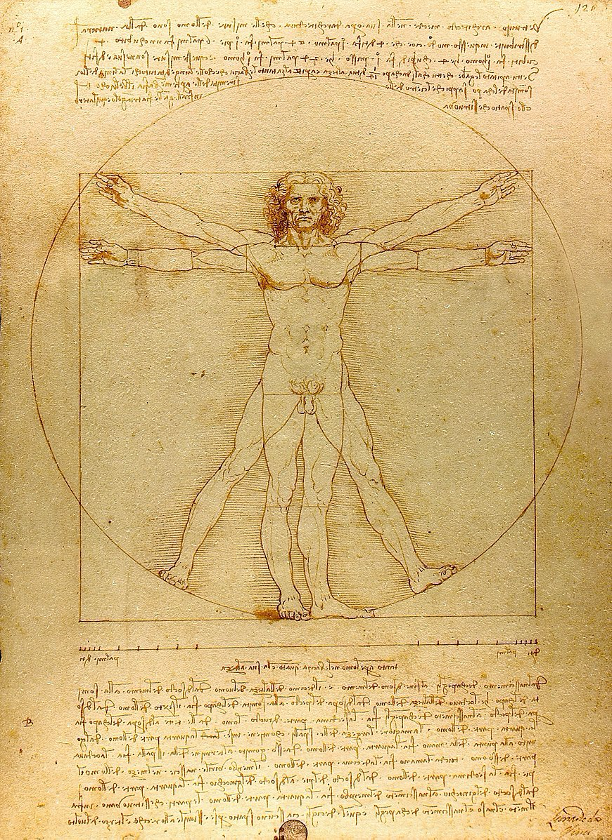

Leonardo designed and engineered a wide variety of tools, machines, and other conceptual inventions. One of the most iconic drawings is the (8.22) Vitruvian Man, drawn in 1492, with ink on paper, the man surrounded by a circle based on ideal human proportions. In Leonardo’s journals, page after page describes drawings of flying machines, musical instruments, pumps, cannons, and many others. The central framework of the human-powered ornithopter (8.21) shows a lightweight structure designed to enable a person to fly. Mechanical wings give the ornithopter its power for lift.

Image 2.7 da Vinci, Vitruvian Man

And for even more examples of da Vinci’s drawings, follow the link below:

Stop and Think

- Art representing the human body requires some familiarity with anatomy, external if not internal. How do you think art enhances our understanding the human body today? Can you think of any examples?

- If you have taken a biology or anatomy class, you have surely seen a graphic presentation of the human body or of a system within the human body. Do you think that a drawing of the circulatory system, for example, would be considered art? Why or why not?

- Why do you think that in our current moment we tend to keep the realms of science and art separated?

- Whis of da Vinci’s drawings of inventions do you think has the most relevance today?

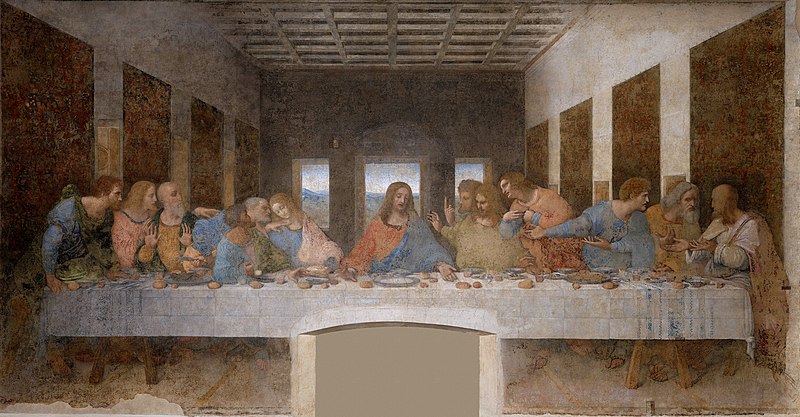

Da Vinci’s most famous pieces, the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, are part of the Western artistic canon. For more comprehensive commentary on each of these pieces, consult the videos below:

Leonardo, Mona Lisa – Smarthistory

Image 2.8 da Vinci “Mona Lisa”

And for the Last Supper:

Leonardo, Last Supper – Smarthistory

Image 2.9 da Vinci, The Last Supper

Write a 500-word essay using one of the following prompts:

- Thick Description and Analysis: Choose one work of art from this chapter and provide a detailed (200 word) description of it. Then discuss the relevance of the piece as you see it. These are world-famous works in part because they speak to a near-universal of the human condition. What do you think the artwork reveals about being human, again in your own experience. What does it make you think about?

- What would you say was the most important function of art during the Renaissance? What do you think was the primary factor influencing its development? What do you think it provided ordinary people of the day? How do you think that has changed in our current moment? Choose one artwork from the chapter to substantiate your position.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Adapted by Monica Krupinski

All chapter images in the Public Domain except where otherwise noted.

Betts, Kristine. “The Curiosity of Leonardo da Vinci.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Medieval World. Colorado Springs,

CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020, CC BY-NC 4.0 License

Fosmire, Ed. “Defining Art from the Medieval Period to Today” in Introduction to Art Concepts. https://www.oercommons.org/courses/introduction-to-art-concepts). CC-BY

Nash, Mark. “Emerging from the Middle Ages under the Influence of Francis of Assisi.” HUM 122 OER. https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/76857. CC-BY

“What even is color?” https://www.wisc-online.com/learn/humanities/visual-arts/flx1413/what-is-color Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Michelangelo’s Graffiti?” https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/new-research-says-michelangelo-may-have-made-carving-palazzo-vecchio-180976310/ Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Art in the Italian Renaissance Republics” https://smarthistory.org/reframing-art-history/art-italian-renaissance-republics/ Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Mannerism” https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/high-ren-florence-rome/pontormo/a/mannerism-an-introduction Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Quiz on Mannerism” https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/high-ren-florence-rome/pontormo/e/mannerism Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Even more about Mannerism.” https://www.coursehero.com/study-guides/boundless-arthistory/mannerism/ Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Michelangelo wrote sonnets too!” https://fod-infobase-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/p_ViewVideo.aspx?xtid=59658&tScript=0 Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“The Complexity of Michelangelo and His Legacy” https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/high-ren-florence-rome#michelangelo Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“More on Michelangelo and Florence” https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/high-ren-florence-rome#michelangelo Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Introduction to da Vinci” https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Art/A_World_Perspective_of_Art_Appreciation_(Gustlin_and_Gustlin)/08%3A_Renaissance_-_The_Growth_of_Europe_(1400_CE__1550_CE)/8.02%3A_Renaissance_Artists Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci” http://www.drawingsofleonardo.org Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Leonardo, Mona Lisa – Smarthistory” https://smarthistory.org/leonardo-mona-lisa/ Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Leonardo, The Last Supper – Smarthistory”https://smarthistory.org/leonardo-last-supper/ Accessed 22 Dec 2022