4 Chapter 4 THE SELF: Portraiture and the Visual Arts

Chapter 4

THE SELF: Portraiture and the Visual Arts

in the Northern Renaissance

Learning Objectives

Guiding question: How do the arts both express our sense of self and impact our vision of ourselves, both individually and collectively?

- Analyze how the arts both express our sense of self and impact our vision of ourselves, both individually and collectively.

- Evaluate representations of humanity included and excluded in Renaissance art.

- Consider themes of Northern Renaissance art and how they differed from that of the Italian Renaissance.

THE PERCEIVER AND THE PERCEIVED

As we look back through the centuries and consider the distance between the artist and the subject—or the perceiver and the perceived—we may want to reflect upon the ways power still influences art, even outside the religious sphere. This requires us to think in ways that may not immediately be familiar to us, such as considering the voices of the marginalized or unheard throughout history. Though we may not realize it, history that we have learned in school is very often the history of the powerful or of the oppressor. In the past several decades, however, scholars and educators have begun to introduce us to a wider variety of perspectives, ones that may seem unfamiliar or initially challenging to encounter, but ones which are equally valid and ones which expand our understanding of the world both before and during our own lifetimes.

For a quick introduction to an approach of feminist movements, read the following excerpt from Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, and Sonny Nordmarken:

“History is also everybody talking at once, multiple rhythms being played simultaneously. The events and people we write about did not occur in isolation but in dialogue with a myriad of other people and events. In fact, at any given moment millions of people are all talking at once. As historians we try to isolate one conversation and to explore it, but the trick is then how to put that conversation in a context which makes evident its dialogue with so many others—how to make this one lyric stand alone and at the same time be in connection with all the other lyrics being sung.”

—Elsa Barkley Brown, “’What has happened here,’” pp. 297-298.

Feminist historian Elsa Barkley Brown reminds us that social movements and identities are not separate from each other, as we often imagine they are in contemporary society. She argues that we must have a relational understanding of social movements and identities within and between social movements—an understanding of the ways in which privilege and oppression are linked and how the stories of people of color and feminists fighting for justice have been historically linked through overlapping and sometimes conflicting social movements. In this chapter, we use a relational lens to discuss and make sense of feminist movements, beginning in the 19th Century up to the present time. Although we use the terms “first wave,” “second wave,” and “third wave,” characterizing feminist resistance in these “waves” is problematic, as it figures distinct “waves” of activism as prioritizing distinct issues in each time period, obscuring histories of feminist organizing in locations and around issues not discussed in the dominant “waves” narratives. Indeed, these “waves” are not mutually exclusive or totally separate from each other. In fact, they inform each other, not only in the way that contemporary feminist work has in many ways been made possible by earlier feminist activism, but also in the way that contemporary feminist activism informs the way we think of past feminist activism and feminisms. Nonetheless, understanding that the “wave” language has historical meaning, we use it throughout this section. Relatedly, although a focus on prominent leaders and events can obscure the many people and actions involved in everyday resistance and community organizing, we focus on the most well known figures, political events, and social movements, understanding that doing so advances one particular lens of history.

Additionally, feminist movements have generated, made possible, and nurtured feminist theories and feminist academic knowledge. In this way, feminist movements are fantastic examples of praxis—that is, they use critical reflection about the world to change it. It is because of various social movements—feminist activism, workers’ activism, and civil rights activism throughout the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries—that “feminist history” is a viable field of study today. Feminist history is part of a larger historical project that draws on the experiences of traditionally ignored and disempowered groups (e.g., factory workers, immigrants, people of color, lesbians) to re-think and challenge the histories that have been traditionally written from the experiences and points of view of the powerful (e.g., colonizers, representatives of the state, the wealthy)—the histories we typically learn in high school textbooks.

To be sure, plenty of other perspectives to our understanding of history exist and can enrich our understanding of the past, but for our purposes, try to entertain perspectives of gender and class as we look at the rise of portraiture. Keep always in mind who is not represented or who is underrepresented, and how those omissions have contributed to our understanding of what life was like in the past.

Stop and Think

- Which people do you think were underrepresented in Renaissance art? Challenge yourself to investigate your answer and see if examples exist.

- Why do you think certain groups of people are historically underrepresented in “great art”? How do you think that affects our perception of beauty, even of art itself?

- What do you think a portrait reveals? How much of an understanding can we get from one still image? Think of this in the day of the selfie–carefully curated for Instagram–and how many photos you take before getting the perfect one.

- How do you think “filters” of the day were used in Renaissance portraiture? Do you think artists enhanced or downplayed features of the subjects of the paintings?

As we saw in Florence, powerful families and societal structures influenced every element of life, from religion to work nutrition to art. The same would be true in Northern Europe, particularly in the Flemish city of Bruges as well as Antwerp, London, and Paris. One significant difference from the Italian Renaissance artists and thinkers, however, is that Northern Europeans would take a more pessimistic (realistic?) view of the power of the Church and of nobility. Rather than regarding religious works only as representations of the glories of God, Northern Europeans were more likely to add in a critique of the corruption of the Church. Artists, too, would portray life’s suffering and hardship instead of a purely bucolic view of life, whether the content was secular or religious in nature. Let’s examine one example of each.

For our example of religious content, let’s begin with Descent from the Cross (1443) by Rogier van der Weyden. Here we see an emotional moment, not of holy jubilation but of intense sorrow and defeat. Central to the image is the lifeless body of Christ as it is removed from the cross, an expression of his undeniable humanness. Also we see his mother Mary, her body limp with grief, below him. The expressions of pain and mourning on the other figures are individual and expressive manifestations of bereavement.

Image 4.1 Rogier van der Weyden Descent from the Cross

Watch this video from the Prado Museum below for a much more detailed examination of the painting:

video for Descent from the Cross

Let’s now briefly look at a secular example. Joos de Momper the Elder’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (c. 1620s) depicts an intersection of the secular form of landscape with the Greek mythological tradition. Though the theme of this painting is not one of sorrow, it is instructive because of its non-Christian subject in Icarus and its focus on the form of landscape depicting a center of commerce in the background. We see Icarus here in flight above a coastal town as work is conducted below him. (Contrast this with the more recognizable Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, attributed to Pieter Brueghel the Elder in 1560.)

Image 4.2 Joos de Momper Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (c. 1620s)

Read below for a more comprehensive introduction to the Northern Renaissance:

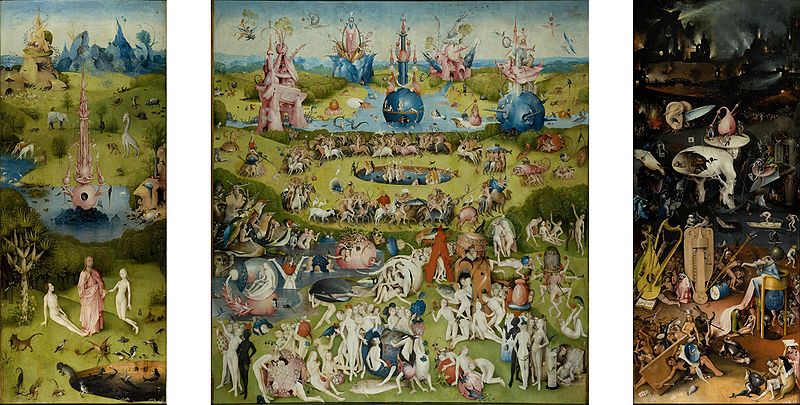

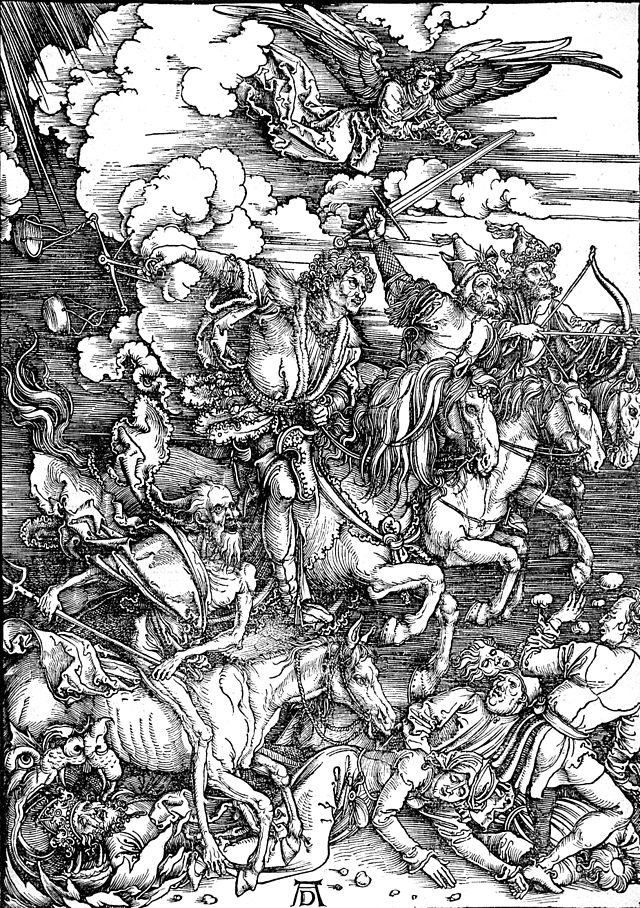

Finally, take an in-depth look at four works from the Northern Renaissance, two portraits and two depictions of fantastical scenes. Below each image is a link to a detailed explanation of each piece.

Image 4.3 Hieronymus Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights

Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights

Image 4.4 Albrecht Durer, Self-Portrait

Image 4.5 Albrecht Durer, Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

Durer, Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

Image 4.6 Hans Holbein the Younger, Christina of Denmark

Holbein the Younger, Christina of Denmark

Stop and Think

- Try to characterize the differences you notice between the Northern Renaissance and Italian Renaissance in terms of art, religion and cultural emphasis.

- Can you identify any patterns in the current moment that might reflect something similar?

Adapted by Monica Krupinski

All chapter images in the Public Domain

“Video for Descent from the Cross” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_5_gBoW69Wk Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Printing and Painting in Northern Renaissance Art” https://smarthistory.org/reframing-art-history/printing-painting-northern-renaissance-art/ Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_5_gBoW69Wk Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Albrecht Durer, Self Portrait” https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/northern/durer/v/albrecht-d-rer-self-portrait-1500 Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Albrecht Durer, Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/northern/durer/a/drer-the-four-horsemen-of-the-apocalypse Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Holbein the Younger, Christina of Denmark” https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/northern/holbein/v/hans-holbein-the-younger-christina-of-denmark-duchess-of-milan-1538 Accessed 22 Dec 2022