6 Chapter 6 HUMANISM: The Rise of Secular Thought

Learning Objectives

Guiding question: How does our view of humanity shape the policies and practices of a culture, a particular social class, and those we put in practice for ourselves?

- Evaluate how our view of humanity shapes the policies and practices of a culture, a particular social class, and those we put in practice for ourselves.

- Apply the understanding of the paradoxes of change to concrete examples found in human history and human art

CHAPTER SIX

HUMANISM: THE RISE OF SECULAR THOUGHT

As we move toward the end of the Renaissance, let’s think back to some of the major themes we have considered in terms of the role of religion, the structures of power, the socioeconomic manifestations of that power, and the move toward a more scientific, less spiritual examination of life. Of course, this will not displace the influence of religion entirely but rather it will offer broader alternatives to the ways in which humans consider their place in the world. The Enlightenment is the intellectual movement that will ultimately result from this shift in perspective and will bring us closer to ideas of equality, individuality, and representative democracy. Before we can make that intellectual leap entirely, though, let’s look at the foundations of this enormous shift toward the secular: the movement we call Humanism.

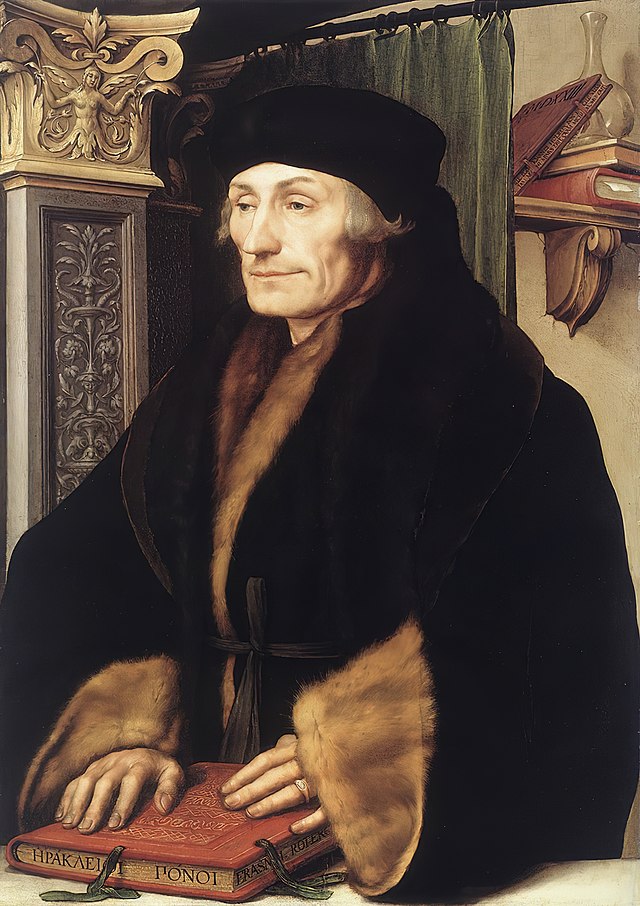

Image 6.2 Holbein the Younger, Erasmus

DISRUPTING THE POWER OF THE CHURCH

In England, the dissolution of monasteries was a manifestation of the king’s own desire for the expansion of his power, to be sure, but it also represented an early example for the scope and difficulty of separating the religious and secular realms. Today, of course, we take for granted the separation of church and state as enshrined in the US Constitution, but in the 1530s, this was a radical departure from the norm and proved to be enormously disruptive. For a more comprehensive look at the origins and reactions to the dissolution in England as well as interactive resources to investigate the results of this policy, follow this lesson from the British National Archives:

Image 6.2 Holbein the Younger, Henry VIII

Desiderius Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536), a Dutch philosopher, would come to represent early Humanist thought. Though his views did not entirely break with those of the Christian tradition, his writings on education and the political sphere surely did offer perspectives considered threatening to the power and position of the Church in Europe. For example, he felt that both males and females were both capable of flourishing with an education, and that education afforded us the opportunity to enjoy and understand the human experience more fully. In fact, he felt that education separated humans from “beasts” and was a necessary part of the socialization process. This perspective serves as a firm foundation for Enlightenment thought. Similarly, Erasmus would suggest that the best means of solving disputes would involve a council of numerous members through arbitration—an idea in direct opposition to Machiavelli’s thoughts in The Prince—and that the needs and desires of a prince should be weighed against the needs of his people. Though Erasmus does not entirely disregard a monarchical structure, we nonetheless see the underpinnings that would allow the development of representative systems of government in his writings.

Stop and Think

- Why do you think people were suspicious of Humanism during the Renaissance? Do you see any parallels to today’s cultural moment?

- Considering that many thinkers of the time offered ties between the religious and secular worlds, why do you think the Church viewed Humanism as such a threat?

INTELLECTUAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL DISCOURSE ON POWER AND GOVERNANCE

As we move toward the Enlightenment, the role of the individual has become the focus of philosophical inquiry and discourse. A foundational premise that will mark this shift is the notion of a social contract between the governing body and the governed. Watch this short video for a brief explanation of the concept:

Thomas Hobbes was a proponent of the social contract, though he felt that government was most effective if it was headed by an absolute sovereign (monarch). According to Hobbes, a sovereign would result in more consistency in governing since he claimed that in the state of nature people would take all they could for themselves, including the possessions and bodies of those who were weaker. He had quite a negative view of humans, viewing the state of humankind as anarchic or at least dominated by the strong, and suggested that the best determinant of self-preservation would be to agree to a social contract in which the individual gives up all rights to the sovereign. This sovereign was only viable if they were agreed to by their subjects. In this way, he opposes the notion of the divine rule of kings and the idea of royal lineage. In his most famous work, Leviathan, he will outline these ideas in detail.

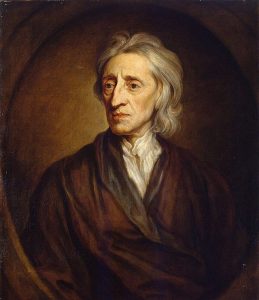

John Locke did not believe in the divine right of kings, which means that a king is king because God made him so,

and therefore whatever he does is approved by God. Instead Locke believed there was a social contract that was given

by the people to the ruler. This included life, liberty and property and was based on the consent of the people who

were being governed. So if the government broke this commitment, it could be overthrown. The British had a tradition

of this belief since they signed the Magna Carta in 1215, which established the idea that even kings had to obey the

laws of the land. Eventually Parliament gained enough power to keep the king in check. Locke also believed that

everyone was born with a mind that was a tabula rasa or blank slate and that people are shaped by their life

experiences. So, if people could eliminate those bad experiences, an ideal society should develop. It also means that

children need to be educated and trained.

Image 6.3 Godfrey Kneller, Portrait of John Locke

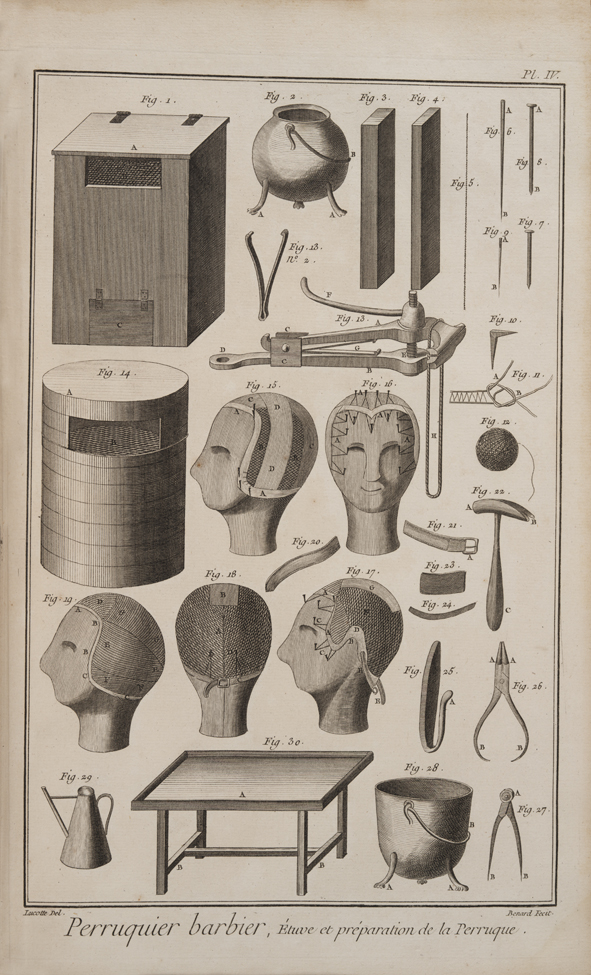

Denis Diderot was the editor of Encyclopédie, to which he contributed articles about aesthetics, ethics, social

theory, the arts and crafts, religious topics, and the philosophy of history. His Encyclopédie was published in France

between 1751 and 1772. There were 11 volumes and more than 29,000 plates, and their stated goal was to collect all

the knowledge in the world into a single place. Many of the philosophes of the Enlightenment contributed articles

including Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu and Diderot. One thing to keep in mind is that the Encyclopédie included

information that was written in a way to be controversial. The writers questioned the church and the long accepted

beliefs about the Bible and its teachings. This led to repression by leaders of the church who did not want its ideas to

be accessible to their congregations. Some of the writers of the articles were jailed for their contributions

Image 6.4 Wigmaking supplies, Diderot’s Encyclopedia

Adam Smith was a Scottish philosopher who is known as the father of modern economics. He wrote The Wealth of

Nations which discussed Capitalism and the free market and he said that while men may be naturally selfish, the free

market would work for the good of society and keep prices low. He also discussed laissez faire, or supply and demand,

which was the idea that trade between groups of people without economic intervention or regulation would be the

most beneficial to society. His ideas were extremely influential and they were written and published just as nations

were moving away from the rule of monarchs and establishing new economies.

Watch the first few minutes of the following video to understand how Adam Smith’s ideas formed the basis of capitalism as we have come to understand and live it even today:

These thinkers were foundational in the move towards the modern liberal democracy that would come to be seen in the Enlightenment. As Noah Levin writes:

Liberal democracy is a liberal political ideology and a form of government in which representative democracy operates under the principles of classical liberalism. It is also called western democracy. It is characterized by fair, free, and competitive elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into different branches of government, the rule of law in everyday life as part of an open society, and the equal protection of human rights, civil rights, civil liberties, and political freedoms for all people. To define the system in practice, liberal democracies often draw upon a constitution, either formally written or uncodified, to delineate the powers of government and enshrine the social contract. After a period of sustained expansion throughout the 20th century, liberal democracy became the predominant political system in the world.

A liberal democracy may take various constitutional forms: it may be a constitutional monarchy (Australia, Belgium, Canada, Japan, Norway, Spain and the United Kingdom) or a republic (France, India, Ireland, the United States). It may have a parliamentary system (Australia, Canada, India, Ireland, the United Kingdom), a presidential system (Indonesia, the United States), or a semi-presidential system (France).

Liberal democracies usually have universal suffrage, granting all adult citizens the right to vote regardless of race, gender or property ownership. Historically, however, some countries regarded as liberal democracies have had a more limited franchise, and some do not have secret ballots. There may also be qualifications such as voters being required to register before being allowed to vote. The decisions made through elections are made not by all of the citizens, but rather by those who choose to participate by voting.

The liberal democratic constitution defines the democratic character of the state. The purpose of a constitution is often seen as a limit on the authority of the government. Liberal democracy emphasizes the separation of powers, an independent judiciary, and a system of checks and balances between branches of government. (Levin)

Stop and Think

- The United States Constitution is considered to be an effective example of Enlightenment ideals brought into practice. Why do you think the framers of the Constitution intended for it to be a “living” document? (Consider that there have been 26 Amendments.)

- How do you think that the Constitution limits the authority of the government, and why do you think that is crucial for a successful democracy?

- Do you think that the US Constitution would have been (and would still be) successful without a capitalist foundation?

- Why do you think that the Church might have wanted to restrict access to informative texts like Diderot’s Encyclopedia? Why do you think that religious groups can sometimes view knowledge as a threat?

- Do you think the idea of a “social contract” has lived up to expectations? Can you think of any examples of the social contract being broken in everyday life?

RECONSIDERING WHAT IT IS TO BE HUMAN–A MOVE TOWARD ENLIGHTENMENT

With the end of the humanism of the Renaissance came many changes to European culture. Philosophers and scientists

met to discuss the changing world around them. Absolute monarchs began to lose their hold on their subjects. There was a

conscious engagement with social issues. Revolution was in the air in the thirteen American colonies and in France. New

religious ideas began to form, such as the Deists, who believed that a single God existed, though some considered God as a

mechanism that kept the universe working, rather than a personal God who communicated with humans. In addition to

Deism came new ways to think of humans who did not believe in God at all but lived their lives as skeptics, atheists or

materialists. We call this time The Enlightenment or the Age of Reason because it “stressed reason, logic, criticism, and

freedom of thought over dogma, blind faith, and superstition. The Enlightenment also argued that human life and character

could be improved through the use of education and reason. The mechanistic universe – that is to say, the universe when

considered to be a functioning machine – could also be altered. The Enlightenment thus brought interested thinkers into

direct conflict with the political and religious establishment.” They questioned traditional ideas, customs, and values and

transferred their faith in God to a belief in reason and science.

Scientific revolution

First let’s look at the scientists who made significant contributions to the changes. The first was Francis Bacon, an

English philosopher and scientist who lived from 1561 to 1626. Bacon wrote treaties that became the basis of the

scientific method. In other words he believed that we should use both deductive and inductive reason to study

everything. Bacon published his thoughts which are sometimes called the “Baconian Method” in a book, Novum

Organum Scientiarum. Bacon’s method begins with observation and a description of the facts, then he organizes his

facts into categories, and then he uses reasoning to eliminate what cannot be correct. In 1862 his biographer William

Hepworth Dixon said “The obligations of the world to Bacon are of a kind which cannot be overlooked. Every man who

rides in a train, who sends a telegram, who follows a steam plough, who sits in an easy chair, who crosses the Channel

or the Atlantic, who eats a good dinner, who enjoys a beautiful garden, or undergoes a painless surgical operation,

owes him something.” Some of the references are obviously dated, but the point he makes is that much of the life we

enjoy now has happened due to the innovations of Bacon and men like him. Enlightenment thinkers that followed

Bacon used his processes to move beyond the study of science. They applied scientific processes to study economics,

politics, and the arts.

Another significant scientist is Sir Isaac Newton was born on Christmas Day in 1642 in Lincolnshire, England, three

months after his father died. Newton was a scientist who used observation, trial and error, and testing to determine if

his theories were correct. He studied the composition of light and learned that white light could be split into multiple

colors, which led to the modern study of physical optics. He studied the laws of mechanics and developed the three

laws of motion which led to the law of gravity. His studies in math led to the field of calculus. Newton’s Mathematical

Principles of Natural Philosophy was one of the most important works in the history of science. The philosophes of the

Enlightenment followed his lead and used his ideas to apply scientific methods to more than just science. If you take a

physics class or a calculus class today, you still study the principles developed by Newton.

Enlightened Monarchs

There were some European rulers who tried to make changes to the way they ruled their kingdom based on what

they read in the essays and writings of the enlightenment philosophers. Most of the changes they made were

superficial and did not last. But we can think of them as enlightened despots. Frederick II, sometimes called Frederick

the Great of Prussia reigned from 1740 to 1786. He invited the philosopher Voltaire to come to his court. Voltaire

visited for two years and participated freely in court activities. The image below shows Frederick in the center in a dark

blue tunic with Voltaire seated two seats to the left and engaged in conversation with the king. Frederick was

enamored of French culture and only spoke French. He was drawn to the arts and wrote music and poetry and tried to

make Prussia more modern.

Catherine I of Russia, often called Catherine the Great was the first woman to rule Imperial Russia during what

some called the Golden Age. Her goal was to westernize Russia and make it more efficient and productive. She focused

on domestic reform but was plagued by a Peasant Revolt. She supported the ideas of the Enlightenment and was a

strong supporter of the arts. Catherine communicated with Voltaire, Diderot and d’Alembert, and when these men

who were writing the Encyclopédie were threatened in France for the content of their articles, Catherine offered to let

them come to work and then publish in Russia. She wrote often to Voltaire, liked his theories of the enlightened ruler

and wanted to be considered one of them. In 1766 she established a Commission to discuss the needs of the Russian

Empire and to find ways to improve it. Many of the suggestions were those of the philosophers of the enlightenment,

but they were too far reaching and eventually the commission disbanded without implementing any changes.

Catherine also knew about the ideas of John Locke and tried to improve opportunities for the education of Russian

children.

Stop and Think

- Do you think an enlightened monarch would be possible in today’s world?

- Do you think monarchy is a completely outdated form of government, or do you envision a way in which a monarchy might help a country? Remember to think globally here, not just in terms of the United States.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Adapted by Monica Krupinski

All chapter images in the Public Domain

Betts, Kristine. “The Rise of the Enlightenment.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Medieval World. Colorado

Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Noah Levin. 2.3: Three Types of Democracies- Classic Republicanism, Liberal Democracy, and Deliberative Democracy is shared under a CC BY license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Noah Levin

Dr. Bonnie Noble, “Printing and painting in Northern Renaissance art,” in Smarthistory, December 16, 2021, accessed November 20, 2022

“Dissolution of the Monarchies” https://bit.ly/32k9Mlp Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“The Social Contract” https://bit.ly/32k9Mlp Accessed 22 Dec 2022

“Adam Smith” https://www.khanacademy.org/economics-finance-domain/ap-macroeconomics/basic-economics-concepts-macro/introduction-to-the-economic-way-of-thinking-macro/v/introduction-to-economics Accessed 22 Dec 2022