11 Chapter Eleven: Safe Environments for Preschoolers

Chapter 11: Creating Safe Environments

Much of what was learned about environments for toddlers still applies here, so you may want to revisit those chapters this week in addition to reading chapter 11. By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Connect classroom design to safety and injury prevention.

- Discuss ways to handle unsafe behavior by understanding the function of behaviors.

- Describe how teachers can ensure the toys and materials they offer children do not present injury risks and are nontoxic.

- Explain ways adults can support safe and developmentally appropriate use of technology.

- Lists ways to protect children from choking, poisoning, burns, drowning, and falls.

- Describe strategies for teaching children about safety.

- Illustrate why outdoor play is essential to health and well-being.

- Describe elements of a safe outdoor play space.

- Recognize the importance of impact absorbing surfacing under equipment.

- Explain what use zones are.

- List age appropriate outdoor play equipment for each age group.

- Identify hazards on outdoor play equipment

- Develop a safety checklist to monitor the safety of the outdoor space.

- Outline ways to protect children from the weather, the sun, insects, drowning, and poisoning.

- Discuss how to keep children safe as pedestrians, in motor vehicles, and while on field trips.

- Describe the importance of risky play.

Introduction

Designing an effective and engaging classroom environment takes careful thought and planning, but it’s important. A well-organized classroom that is interesting, orderly, and attractive contributes to children’s participation and engagement with the learning materials and activities. This engagement, in turn, contributes to children’s learning.

Let’s look at it from a child’s perspective. We want children to feel safe and comfortable in the classroom. We want them to be interested in the learning activities and to take full advantage of being at school and take full advantage of the activities you’ve planned and the materials you’ve selected. It can be helpful to get down at a child’s level and take a look at the classroom. Does it feel welcoming and inviting? Is there enough room to move, make choices, and stay involved with a toy or activity or project? And does the room help the child know what to do and what’s expected?

Designing an Effective and Safe Classroom Environment

There are all sorts of classrooms. They differ by size and shape, amount of light and wall space, placement of sinks and counters, and amount of storage. Figuring out how to design the physical space and to maximize children’s interactions within the space will take some time. Make a floor plan. Move things around. Take a look at other classrooms and see what works.

Here are a few things to think about when designing your space and making it as workable as possible. Think about the number of interest areas or centers that you want or need for the group of children. Arrange the space so that noisy areas are separated from quiet areas. Locate centers next to needed storage or equipment. Use furniture or other items to provide boundaries. But, make sure that the adults can see all of the areas of the room.3

Factors to Consider

Space and boundaries:

- Are the centers clearly defined with furniture, rugs, or shelves?

- Is there enough space for all children to easily move about the room?

- In each defined area, is there adequate space for the number of children using it?

Proximity and distance:

- Are the quiet and noisy areas in proximity or separated?

- Are centers located near things that children need to complete projects (art center near sink, puzzle or game shelves within reach of tables, etc.)?

- Are teachers able to view children in all centers?

Home and culture:

- What home-like features are included in the classroom?

- How is(are) the culture(s) of the local community reflected in the classroom?

Flexibility and permanence:

- How does the space accommodate gross motor activity?

- What aspects of the physical space cannot be changed (cost or structural issues) and are challenging to overcome (e.g., limited access to natural light, cumbersome cubbies, etc.)?

Engagement and challenging behaviors:

- Are there areas of the classroom where challenging behaviors are more likely to occur?

- Are there areas where typically children are positively engaged in classroom activities?

Traffic patterns:

- Can children move easily from space to space?

- Is running and wandering discouraged?

Material selection:

- Are materials chosen to support development and learning?

- Are they culturally relevant and meaningful to the children?

- Is there is a sufficient variety and quantity (without overwhelming children)?4

|

|

Figure 11.2 – This large space was transformed with this rug and arrangement of materials and furniture.6 |

Grouping of Children

Teachers want to be intentional about how they group children, whether it’s a decision made in the moment or as part of lesson planning. Match the size of the group with the purpose of the activity. Think about the children who will be in the group. Young children need opportunities to participate and learn with the whole group, small groups, and they will thrive with a bit of one-on-one time with an adult.7

Large groups are good for:

- Introducing concepts

- Building community

- Conducting routine activities

Small groups are good for:

- Maximizing back and forth interactions

- Peer modeling of skills

- Guiding instruction

One-on-one interactions are good for:

- Tasks requiring complex skills

- Instance when a child needs specific direction and assistance8

|

|

Pause to ReflectHow is considering group size related to safety? What might teachers need to observe for to determine if the group sizes are working well for the children? |

Every early childhood environment is full of pros and cons; it is how educators work with the many characteristics of a classroom that can make a tremendous difference. Teachers can be surprised by the results when they:

- Assess the spaces for both limitations and strengths.

- Strategize how to optimize what they have to work with in their classrooms.

- Try a different arrangement, see what happens, and then modify based on what is working and what is not.

Figure 11.3 – These shelves are in a classroom for 3-year-olds. What adjustments

might need to be made to meet the needs of the children and keep them safe?9

Sometimes a modification can be minor (raising or lowering a shelf, “stop” signs over unavailable areas, masking tape to better define a space, etc.). This highlights the “work-in-progress” nature of early childhood environments. As the needs of children change, the room may need minor changes or have to be rearranged completely to meet those needs.10

|

|

A Few More Considerations for Environmental Design When designing classroom environments, there are some other considerations to keep in mind: Rotations:

|

Interpersonal Safety

Children can behave in ways that hurt themselves or others so teachers must prepared to handle unsafe behaviors in their duty to protect children from injury. An important way to think about behavior is as a form of communication. Young children let us know their wants and needs through their behavior long before they have or can use words in the heat of the moment. They give us cues to help us understand what they are trying to communicate.

Early childhood educators can help children by interpreting their cues and responding to meet their needs. The following example illustrates the importance of responding to the possible meaning behind behavior:

Javon bites Blair because he wants the block she is playing with and we remove Javon from the situation. Not only are we not responding to his want or need, but we are taking him out of the context where he can learn to communicate his feelings in a way that doesn’t hurt others.

Forms and Functions of Behavior

There are many reasons a child might use specific behaviors. This is why it is important for adults to carefully observe children, pay attention to their cues, get to know them, and know what part of the schedule gives them a hard time to better understand what they are trying to tell us through their behavior.12

Each behavior has a:

FORM = the behavior the child is using to communicate

AND A FUNCTION = the reason or purpose the child is using that behavior13

Table 11.1 – Examples of Forms and Possible Functions of Behaviors15

|

Form of Communication |

Possible Functions of Communication |

|

Toddler biting |

|

|

Preschooler hitting |

|

Form and function are also shaped by culture. Children are socialized to express their feelings in culturally acceptable ways. It is important to talk with families so you can look for acceptable ways that children express themselves in a culturally respectful way.

As you have probably already experienced—it is not always easy to figure out the meaning of a child’s behavior. To add to the complexity of understanding the meaning of behavior:

- A single form of behavior may serve more than one function. For example, a toddler might use biting (form) for different functions (“I want the toy you have.” “I want to play with you but don’t know how to let you know.” “I’m tired.” “I’m frustrated because you don’t understand what I am trying to tell you.” “I want some attention.”)

- Several forms of behavior may serve one function. For example, a child’s purpose (function) may be to build with their favorite blocks, but they use different forms of behavior (biting, yelling, grabbing, running away with the blocks, sharing) based on how they feel that day, who is playing in the block area, or based on their cultural expectations.

- The meaning of behavior is shaped by culture, family, and the unique makeup and experiences of the individual child. For example, some cultures may express sadness by crying or by having a nonchalant facial expression. Some cultures may express happiness by laughing and being exuberant, while others may expect more restrained behaviors.

Some of these functions of communication become a concern for children’s safety (of the child communicating, the other children, and other people in the environment). Early childhood educators must take the time to understand a behavior’s meaning so that they can help the child replace unsafe forms of communication with forms that don’t hurt others or harm the environment. Pausing to try to figure out the meaning behind a child’s behavior—instead of just reacting to the behavior—can change the way we see a child, the way we respond to a child, and the way we teach a child. Becoming a “behavior has meaning” detective who is always on the lookout for the meaning of behavior will help you keep children safe.16 Take a look at the following example of an unsafe behavior, what it might mean, and what an educator might do to support the child.

|

|

Teacher Emilia says about a child Sarae, “I have to watch her like a hawk or she’ll run down the hall or go out the gate, down the street, and I don’t know where.” So, we could reframe this to: Sarae is an active child. She may naturally be a kinesthetic learner, who needs to move and shake, has extra energy. A teacher can give Sarae positive ways to exercise the way she loves to be. So, whether that’s during choice time, that there is an opportunity for her to dance, for example. Or, there’ s an obstacle course set up for her to maneuver through.

Figure 11.4 – Help keep children stay safe by figuring out the function of their behavior/communication.17 When they are outdoors, the teacher can create opportunities for structured play so that is running with an intention; such as part of a game with her peers. If it’s hard to get her back inside, give her a leadership role. Maybe she’s the one who has the bell that cues everybody that it’s time to line up. So now she’s going to make sure she finds her friends and is the one responsible for bringing the whole group together to go inside. Reframing the behavior and provide positive outlets will not only keep Sarae safe, but it will also communicate to her that how she feels is okay and that she’s being supported, acknowledged, and encouraged.18 |

Taking a Closer Look at Behavior

You may also find it valuable to examine behavior much the way you would injuries and traffic patterns. Gather data about unsafe behaviors:

- When are they happening? Are there specific times of day that children are finding it more challenging to behave/communicate in safe ways?

- Where are they happening? Are there hot spots for challenging behavior? What in the environment might be the focus of the unsafe behavior/communication?

- Why they are happening? What happened before the led up to the behavior? What happened after?

- Who are the behaviors happening between? All children will have times where they communicate with unsafe behavior, but some children may need more adult support in certain contexts (time of day, activity, groupings of children, etc.).

Look for patterns. Reflect on what can be changed in the physical environment, schedule/routine, groupings, and supervision to help prevent children from hurting themselves or others when trying to communicate their needs.

Safe Toys, Materials, and Equipment

Play is a natural activity for every young child. Play provides many opportunities for children to learn and grow – physically, mentally, and socially. If play is the child’s work, then the toys, materials, and equipment in the environment are what will enable children to do their work well and safely.20

Safe Toys

Protecting children from unsafe toys is the responsibility of everyone. Careful toy selection and proper supervision of children at play are still—and always will be—the best ways to protect children from toy-related injuries.21

It is important that educators consider both safety and durability when choosing toys for children. Toys should be constructed to withstand the uses and abuses of children in the age range for which the toy is appropriate.

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) has safety regulations for certain toys. Manufacturers must design and manufacture their products to meet these regulations so that hazardous products are not sold (see Table 3.3).

Table 11.2 – Mandatory Toy Safety Regulations

|

Age |

Regulations |

|

For All Ages |

|

|

Under Age 3 |

|

|

Ages 3-6 |

|

|

For 3 years and older |

|

|

Under Age 8 |

|

In addition to the mandatory standards, many toy manufacturers also adhere to the toy industry’s voluntary safety standards (see Table 3.4).23

Table 11.3 – Voluntary Standards for Toy Safety24

|

Voluntary Standards for Toy Safety25 |

|

Puts age and safety labels on toys |

|

Puts warning labels on crib gyms advertising that they should be removed from cribs when infants can push up on hands and knees to prevent strangulation |

|

Makes squeeze toys and teethers large enough not to become lodged in an infant’s throat |

|

Assures that the lid of a toy chest will stay open in any position to which it is raised and not fall unexpectedly on a child |

|

Limits string length on crib and playpen toys to reduce the risk of strangulation |

Toys should be chosen with care. Teachers should look for quality design and construction. Safety labels to look for include “Flame retardant/Flame resistant” on fabric products and “Washable/hygienic materials” on stuffed toys and dolls. Watch for the hazards listed in Table 3.526.

Table 11.4 – Hazards to Avoid in Toys27

|

Hazards |

Description |

|

Sharp Edges |

New toys intended for children under eight years of age should be free of sharp glass and metal edges. With use, however, older toys may break, exposing cutting edges. |

|

Small Parts |

The law bans small parts in toys intended for children under three. This includes removable small eyes and noses on stuffed toys and dolls and small, removable squeakers on squeeze toys. |

|

Loud Noises |

Some noise-making toys can produce sounds at noise levels that can damage hearing. |

|

Cords And Strings |

Toys with long strings or cords are dangerous for infants and very young children. The cords can become wrapped around an infant’s neck, causing strangulation. Never hang toys with long strings, cords, loops, or ribbons in cribs or playpens where children can become entangled. Remove crib gyms from the crib when the child can pull up on hands and knees; some children have strangled when they fell across crib gyms stretched across the crib. |

|

Sharp Points |

Toys that have been broken may have dangerous points or prongs. Stuffed toys may have wires inside the toy which could cut or stab if exposed. A CPSC regulation prohibits sharp points in new toys and other articles intended for use by children under eight years of age. |

|

Propelled Objects |

Projectiles—guided missiles and similar flying toys—can be turned into weapons and can injure eyes in particular. Children should never be permitted to play with hobby or sporting equipment that has sharp points. |

Check all toys periodically for breakage and potential hazards. A damaged or dangerous toy should be thrown away or repaired immediately.

Age Appropriate Toys

Teachers must keep in mind the ages of children they are choosing toys for, including their typical interests and skill levels. The manufacturer’s age recommendation is a good starting place to ensure that toys are age-appropriate. Warnings such as “Not recommended for children under 3” should be followed.28

Using Technology and Media Safely

Developmentally appropriate use of technology can help young children grow and learn, especially when families and early educators play an active role. Early learners can use technology to explore new worlds, make-believe, and actively engage in fun and challenging activities. They can learn about technology and technology tools and use them to play, solve problems, and role play. But how technology is used is important to protect children’s health and safety.

Technology can be a Tool for Learning

What exactly is developmentally appropriate when it comes to technology for children? In Technology and Interactive Media as Tools in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth through Age 8, the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) and the Fred Rogers Center state that “appropriate experiences with technology and media allow children to control the medium and the outcome of the experience, to explore the functionality of these tools, and pretend how they might be used in real life44.”

Lisa Guernsey, author of Screen Time: How Electronic Media—From Baby Videos to Educational Software—Affects Your Young Child, also provides guidance for families and early educators. For example, instead of applying arbitrary, “one-size-fits-all” time limits, families and early educators should determine when and how to use various technologies based on the Three C’s: the content, the context, and the needs of the individual child. They should ask themselves the following questions:

- Content—How does this help children learn, engage, express, imagine, or explore?

- Context—What kinds of social interactions (such as conversations with families or peers) are happening before, during, and after the use of the technology? Does it complement, and not interrupt, children’s learning experiences and natural play patterns?

- The individual child—What does this child need right now to enhance his or her growth and development? Is this technology an appropriate match with this child’s needs, abilities, interests, and development stage?45

Early childhood educators should keep in mind the developmental levels of children when using technology for early learning. That is, they first should consider what is best for healthy child development and then consider how technology can help early learners achieve learning outcomes. Technology should never be used for technology’s sake. Instead, it should only be used for learning and meeting developmental objectives, which can include being used as a tool during play.

When technology is used in early learning settings, it should be integrated into the learning program and used in rotation with other learning tools such as art materials, writing materials, play materials, and books, and should give early learners an opportunity for self-expression without replacing other classroom learning materials. There are additional considerations for educators when technology is used, such as whether a particular device will displace interactions with teachers or peers or whether a device has features that would distract from learning. Further, early educators should consider the overall use of technology throughout a child’s day and week, and adhere to recommended guidelines from the Let’s Move initiative, in partnership with families. Additionally, if a child has special needs, specific technology may be required to meet that child’s educational and care needs. And dual language learners can use digital resources in multiple languages or translation to support both their home language and English development.

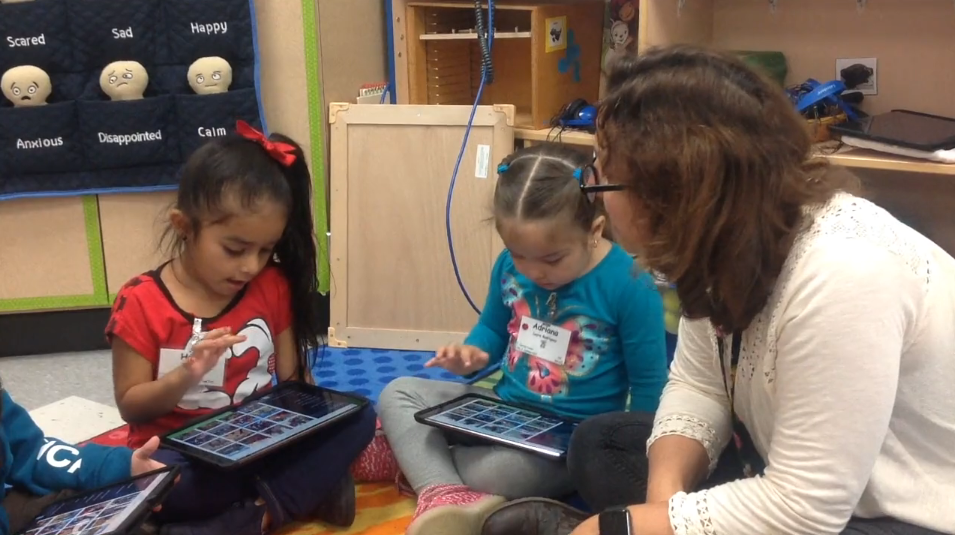

Figure 11.14 – These children and their teacher in a bilingual preschool

classroom are using an app to create a “story” with photos of their recent field trip.46

For Preschoolers

For children ages 2-5, families and early educators need to take into account that technology may be used at home and in early learning settings. New recommendations in the AAP’s 2016 Media and Young Minds Brief suggest that one hour of technology use is appropriate per day, inclusive of time spent at home and in early learning settings and across devices.47 The Department of Health and Human Services supports more limited technology use in early care settings, and more information on their recommendations can be found in Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards.48 However, time is only one metric that should be considered with technology use for children in this age range. Early educators should also consider the quality of the content, the context of use, and opportunities the technology provides to strengthen or develop relationships.

Active versus Passive Engagement

Early childhood educators should understand the differences between passive and active use of technology. Passive use of technology generally occurs when children are consuming content, such as watching a program on television, a computer, or a handheld device without accompanying reflection, imagination, or participation.

Active use occurs when children use technologies such as computers, devices, and apps to engage in meaningful learning or storytelling experiences. Examples include sharing their experiences by documenting them with photos and stories, recording their own music, using video chatting software to communicate with loved ones, or using an app to guide playing a physical game. These types of uses are capable of deeply engaging the child, especially when an adult supports them. While actions such as swiping or pressing on devices may seem to be interactive, if the child does not intentionally learn from the experience, it is not considered to be active use. To be considered active use, the content should enable deep, cognitive processing, and allow intentional, purposeful learning at the child’s developmental level.

|

|

Pause to ReflectDo these children look like they are using technology actively or passively? What do you need to see or know to accurately make this determination?

Figure 11.15 – Two children on a computer49 |

Early childhood educators also need to think of ways they can reduce the sedentary nature of most technology use. Technology can encourage and complement physical activity, such as doing yoga with a video or learning about the plants outdoors with a nature app.

Research points to a widening digital use divide, which occurs when some children have the opportunity to use technology actively while others are asked primarily to use it passively. The research showed that children from families with lower incomes are more likely to complete passive tasks in learning settings while their more affluent peers are more likely to use technology to complete active tasks.

For low-income children who may not have access to devices or the internet at home, early childhood settings provide opportunities to learn how to use these tools more actively. For example, research shows that preschool-aged children from low-income families in an urban Head Start center who received daily access to computers and were supported by an adult mentor displayed more positive attitudes toward learning, improved self-esteem and self-confidence, and increased kindergarten readiness skills than children who had computer access but did not have support from a mentor.

Co-Viewing of Technology

Most research on children’s media usage shows that children learn more from content when parents/caregivers or early educators watch and interact with children, encouraging them to make real-world connections to what they are viewing both while they are viewing and afterward.

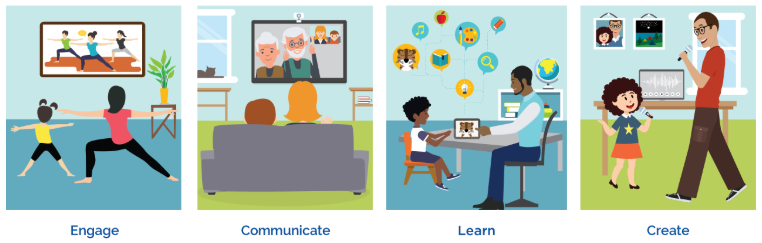

Figure 11.16 – Interacting with children and technology

is the best way to make technology use effective.50

There are many ways that adult involvement can make learning more effective for young children using technology. Adult guidance that can increase active use of more passive technology includes, but are not limited to, the following:

- Prior to the child viewing content, an adult can talk to the child about the content and suggest certain elements to watch for or pay particular attention to;

- An adult can view the content with the child and interact with the child in the moment;

- After a child views the content, an adult can engage the child in an activity that extends learning such as singing a song they learned while viewing the content or connecting the content to the world.

Figure 11.17 – Here are some ways adults can effectively use technology with children.51

Safety Risks of Technology

In addition to the health risks of sedentary activity (in place of active play), there are concerns about privacy and security with any technology. The rights of children under 13 and technology in school are governed by federal laws, but looking at privacy policies is important.

Software and apps may also include advertising and in-app purchasing (generally inappropriate for young children). So early childhood educators should choose software and apps that avoid advertising and in-app purchases.

|

|

In the Ed Tech Developer’s Guide, released by the Office of Educational Technology in April 2015, digital citizenship is defined as “a set of norms and practices regarding appropriate and responsible technology use… and requires a whole-community approach to thinking critically, behaving safely, and participating responsibly online.”52 As early learners reach an appropriate age to use technology more independently, they must be taught about cyber safety, including the need to protect and not share personal information on the internet, the goals and influence of advertisements, and the need for caution when clicking on links. These skills are particularly important for older children who may be using a parent’s device unsupervised. Early childhood educators and administrators should ensure that the proper filters and firewalls are in place so children cannot access materials that are not approved for a school setting.53 |

Not all technology is appropriate for young children and not every technology-based experience is good for young children’s development. To ensure that technology has a positive impact, adults who use technology with children should continually update their knowledge and equip themselves to make sophisticated decisions on how to best leverage these technology tools to enhance learning and interpersonal relationships for young children.

Access to technology for children is necessary in the 21st century but not sufficient. To have beneficial effects, it must be accompanied by strong adult support.54

Preventing Injuries Indoors

Some injuries that early childhood educators should be aware of and intentionally act to prevent in the last chapter were presented in the previous chapter and earlier in this chapter during the discussion about safe toys and art materials. Here is some further information about injuries that are more likely to happen indoors.

Choking

Choking occurs when an object blocks the airway, preventing breathing.55 Infants have the highest rates of choking (140 per 100,000). That risk decreases as they get older and their airway increases in size, with 90% of fatal choking happening in children less than 4 years of age.56

The main way to prevent choking is to recognize that objects that are 1½ inches or less in diameter are higher risk.57 Foods are the most common cause of choking. Having children sit during snacks and meals at an unhurried pace, allowing time for children to properly chew their food helps prevent choking on food. Food is safest when cut into small pieces or served in small amounts. See Table 3.7 for foods that commonly cause choking.

Table 11.7 – Common Choking Hazards58

|

Foods |

Other Items |

|

|

There are many hazards that put children at risk for accidental poisoning, both indoors and outdoors. Poisoning can occur at any time a harmful substance is intentionally or unintentionally ingested. Poisons come in many forms including plants, cleaning supplies, spoiled food, and medications. Children, who are naturally curious and like to explore, are in particular at risk for poisoning.

Figure 11.18 –Lock up harmful substances in cabinets that are out-of-reach of children to prevent poisoning.61

Guidelines to Prevent Poisoning

- Keep all cleaning supplies and chemicals locked.

- All medications should be kept in a locked storage area, out of reach.

- Check medications periodically for expiration dates and properly dispose of expired medications. Some medications become toxic when they are past their expiration date.

- Do not tell children that medication is “candy” as this makes it look more attractive to them.

- Ensure all medications and chemicals are properly labeled. Childproof caps should be on medicine bottles.

- Use safe food practices. (see Chapter 15)

- Never use cans that have bulges or deep dents in them.

- Keep poisonous plants out of reach of children and pets. (see Table 3.8)

- Keep the number for Poison Control near a telephone.62

|

|

Poison Control 1-800-222-1222 |

Burns

Every day, over 300 children ages 0 to 19 are treated in emergency rooms for burn-related injuries and two children die as a result of being burned.

Younger children are more likely to sustain injuries from scald burns that are caused by hot liquids or steam, while older children are more likely to sustain injuries from flame burns that are caused by direct contact with fire.64

Causes of Burns

Burns can be caused by dry or wet heat, chemicals, or electricity (both indoors and outdoors).

- Burns from dry heat can occur from fire, irons, hairdryers, curling irons, and stoves (American Institute for Preventive Medicine, 2012; Leahy, Fuzy & Grafe, 2013).

- Burns from wet or moist heat occur from hot liquids, such as hot water or steam (American Institute for Preventive Medicine; Leahy, Fuzy & Grafe). These types of burns are called scalds. Scalds can occur within seconds and cause serious injury.

- Chemical burns occur from chemical sources and can also cause serious burns when exposed to skin, or if swallowed, whether intentionally or unintentionally.

- Electrical burns can cause very serious injury as they can burn both the outside and inside of the person’s body, causing injury that cannot be seen, and which can be life-threatening.

- Radiation burns can also occur from sources of radiation such as sunlight (American Institute for Preventive Medicine).65

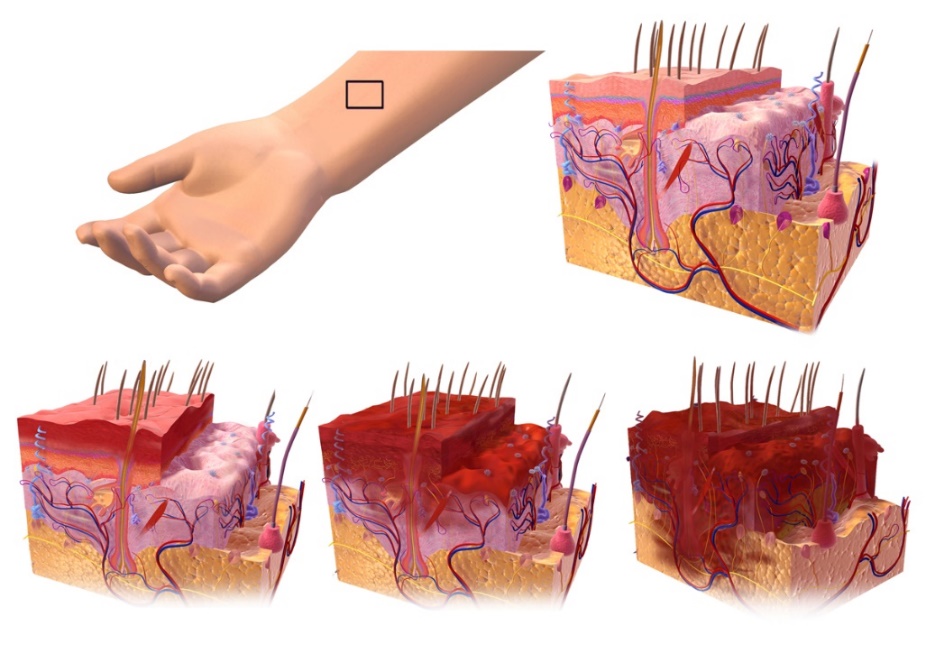

Burns are divided into first, second, and third degree burns.

First degree burns affect only the outer layer of the skin (epidermis). These types of burns are the least serious as they are only on the surface of the skin. First degree burns usually appear red, dry, and slightly swollen (MedlinePlus, 2014). Blisters do not occur with this type of burn. They should heal within a couple of days (American Institute for Preventive Medicine, 2012). A first degree burn is pictured in the bottom left of Figure 3.20.

Second degree burns affect the top layer of the skin and the second layer of skin underneath (dermis). These are more serious than first degree burns. The skin may appear very swollen, red, moist, (MedlinePlus, 2014) and may have blisters or look watery and weepy (American Institute for Preventive Medicine, 2012). A second degree burn is pictured in the bottom middle of Figure 3.20.

Third degree burns are the most serious burn. A third degree burn affects all layers of the skin and may affect the organs below the surface of the skin. The skin may appear white or black and charred (MedlinePlus, 2014). The person may deny pain because the nerve endings in their skin have been burned away (American Institute for Preventive Medicine, 2012). Third degree burns require immediate medical treatment. If teachers suspect a child has a third degree burn, they should immediately call 911. A third degree burn is pictured in the bottom right of Figure 3.20.66

Figure 11.19 – This image shows first, second, and third degree burns.67

Chemical burns can occur anytime a liquid or powder chemical comes into contact with skin or mucous membranes that line the eyes, nose, or throat. Chemical burns may also occur if a chemical is swallowed. These burns can cause serious injury and emergency services should be contacted. If a person receives a chemical burn, the chemical should be removed from the skin by using a gloved hand to brush it off and then wash the area with plenty of cool water. Electrical burns can occur if a person has been using an electrical appliance and is exposed to water or if an electrical short occurs while using the electrical appliance. Using faulty or frayed cords on electrical appliances can result in electrical burns. Electrical burns are a serious injury. Emergency medical services (EMS) should be immediately activated.

Never use oils such as butter or vegetable oil on any type of burn as this can cause further injury. For first or second degree burns flush the area with plenty of cool (not ice cold) water for about 15 minutes or until the pain decreases and cover with a clean, dry bandage. Using ice or ice-cold water can cause frostbite (American Institute for Preventive Medicine, 2012). For major burns remove any clothing that is not stuck to the skin, cover the burned area with a dry, clean cloth, and seek emergency assistance.68

- Install and regularly test smoke alarms.

- Practice fire drills.69

- Train staff to use fire extinguishers.

- Teach children to stop, drop, and roll.70

- Never allow children to use electrical appliances unsupervised.

- Never use electrical appliances near water sources.

- Never use electrical appliances in which the cord appears to be damaged or frayed.

- Never pull a plug from the cord. Always remove a cord from an outlet by holding the base of the plug.

- Cover electrical outlets with childproof plugs. Never allow children to put anything inside an electrical outlet.

- Ensure stoves and other appliances are turned off when finished with them.

- Turn pot handles inward so that a person cannot accidentally bump a handle and spill hot liquids.

- Do not use space heaters and other personal heaters.

- Check to be sure the hot water heater is not set too high. To avoid scalds from hot tap water, hot water heaters should be set to 120 degrees or less (MedlinePlus, 2014).

- Keep chemicals, cleaning solutions, and matches and lighters securely locked and out of reach of children.71

Indoor Falls

While most falls occur outdoors, and this topic is addressed in Chapter 4, they can also happen indoors. Teachers (and adults at home) can prevent falls indoors by

Installing stops on windows that prevent them from being opened more than four inches or install window guards on lower parts of windows. Removing furniture from near windows. Screens should not be relied on to prevent a fall.

Installing safety gates at the top and bottom of staircases. Installing lower rails on stairs that children can reach and use. Making sure the surface of the stairs stays clear.

Teaching children to walk where surfaces may be slick. Preventing these surfaces as much as possible, such as wiping up spills.79

Indoor Water Safety

Small children are top-heavy; they tend to fall forward and headfirst when they lose their balance. They do not have enough muscle development in their upper body to pull themselves up out of a bucket, toilet or bathtub, or for that matter, any body of water. Even a bucket containing only a few inches of water can be dangerous for a small child.

It’s important that early childhood educators follow the safety practices outlined in Chapter 4 for water safety both indoors and outdoors, keep children under active supervision, and be very aware of containers of water.80

Teaching Children about Safety

While it is the adult’s responsibility to keep children safe and children should not be expected to actively protect themselves, teachers should help children develop safety awareness and the realization that they can control some aspects of their safety through certain actions. The earlier children learn about safety, the more naturally they will develop the attitudes and respect that lead to lifelong patterns of safe behavior.

Safety education involves teaching safe actions while helping children understand the possible consequences of unsafe behavior. Preschoolers learn through routines and daily practice and by engaging in language scripts and following simple rules. These scripts and rules may be communicated through voice, pictures, or signs. Children learn concepts and develop skills through repetition, then build upon these as concepts and skills become more complex.

Preschoolers need help to recognize that safe play may prevent injury. Teachers can promote independence and decision-making skills as children learn safe behaviors. Teachers can explain that children can make choices to stay safe, just as they wash their hands to prevent disease, brush their teeth to prevent cavities, and eat a variety of foods to help them grow strong and healthy.

Preschoolers can learn to apply a few simple and consistent rules, such as riding in a car seat and wearing seat belts, even though they are too young to understand the reasons for such rules. For example, four-year-old Morgan says, “Buckle up!” as she gets into a vehicle. Although Morgan lacks the skill needed to buckle the car seat buckle and does not understand the consequences of not being safely buckled into her car seat, she is developing a positive habit. Safety education in preschool focuses on behaviors the children can do to stay safe. It involves simple, concrete practices that children can understand.

Figure 11.20 – Young children can develop habits that keep them safe.35

The purpose of safety rules and guidance is to promote awareness and encourage developmentally appropriate behavior to prevent injury. Teachers may include separate rules for the classroom, playground, hallways, buses, or emergency drills. Limit the number of rules or guidelines, but foster consistency (e.g., three indoor rules, three playground rules) and base them upon the greatest hazards, threats, and needs in your preschool program and community.

Safety guidance is most effective when teachers have appropriate expectations and safety rules are stated in a positive manner. For example, an appropriate indoor safety rule might be stated, “We walk indoors,” rather than the negative, “Do not run indoors.” On the playground, a rule might state, “Go down the slide on your bottom, feet first.” As children follow these rules, acknowledge them for specific actions with descriptive praise (e.g., “Kevin, you sat on the slide and went down really fast! That looked like fun!”).

State rules clearly, in simple terms, and in children’s home languages; include pictures or icons with posted rules to assist all children’s understanding. Children often are more willing to accept a rule when they are given a brief explanation of why it is necessary. Gently remind children during real situations; with positive reinforcement, they will begin to follow safety rules more consistently. As children develop a greater understanding of safety rules, they begin to develop self-control and feel more secure.

Adults are fully responsible for children’s safety and compliance with safety rules and emergency procedures. Safety education for children, which include rules and reinforcement of verbal and picture scripts in children’s home languages (including sign language), is essential for handling emergency situations. Through practice and routines, children are better able to follow the teacher’s instruction and guidance. It is essential that teachers evaluate each child’s knowledge and skill in this area, and provide additional learning activities as needed to ensure that all children can follow emergency routines.

Here are some strategies that teachers can use to help children learn about safety:

- Incorporate safety into the daily routine.

- Involve children in creating rules

- Provide coaching and gentle reminders to help children follow safety rules.

- Acknowledge children’s self-initiated actions to keep themselves and others safe (such as pushing chairs in and wiping up spills)

- Provide time for children to practice safety skills (such as buckling seat belts)

- Introduce safety concepts and behaviors in simple steps.

- Role-play safety-helpers.

- Define emergency and practice what children should do in emergency situations.

- Introduce safety signs.

- Incorporate musical activities and safety songs.

Because of their level of cognitive development, many young children cannot consistently identify dangerous situations. They may understand some safety consequences and can learn some scripts. But adults must be responsible for their safety. Children often act impulsively, without stopping to consider the danger. By learning and following simple safety rules (e.g., take turns, wear a helmet) and practicing verbal, visual, or sign-language scripts, children establish a foundation of lifelong safety habits.36

|

|

Engaging Families

|

Creating Safe Outdoor Environments

Introduction- Outdoor Environments

There are countless benefits to outdoor play for children. Research shows that children who play outside regularly have healthier body weight, improved vision, and immune function, reduced stress, better sleep, improved motor skills. There are substantial immediate and long-term health consequences for children who aren’t able to play outside or get enough physical activity such as increased obesity and chronic diseases. The research also shows us that kids who play outdoors have increased school readiness because outdoor play contributes to better social skills such as cooperation, increased attention span, improved school attendance, and improved brain development and cognition. Physical activity plays a critical role in supporting health and learning.

Being aware of the benefits of outdoor learning as they relate to overall health and school readiness is important so that teachers remember that the outdoor environment is an essential extension of the indoor environment. All the learning that takes place indoors can also take place outdoors. Anything programs do indoors can have an outdoor component.

Consider for just a moment how a program can increase the benefits of outdoor play while also minimizing injury. Reducing risk does not mean limiting play equipment or enforcing rules that restrict children’s ability to move and explore their environment. An ideal playground is one that encourages children to challenge themselves while also preventing little risk for injury. In fact, studies show that playgrounds that are high challenge but low risk are the very best at promoting the goals of outdoor learning. Children get more physical activity, develop better physical, cognitive, social skills and are happier and more resilient when their outdoor play environment is challenging and safe.2

Figure 11.21 – Safe outdoor play is very beneficial to children.3

Playground Safety

When designing an outdoor space for children, it is critical to reduce the risk of injury while increasing the challenge. The first step is knowing what aspects of the actual learning environment are most likely to cause injuries.

Falls from, into, or on equipment are the most common cause of injury. Falls are most likely to occur on equipment that is not appropriate for the age and development of the children. And injuries are most likely to occur when the surface on which a child falls is not sufficiently shock-absorbing. The equipment pieces that are associated with the most injuries include climbers, such as monkey bars or overhead ladders, swings, and slides. About 85% of all playground injuries occur on these three pieces of equipment. And the most common cause of death on playgrounds is strangulation, that’s an injury that chokes the child.

It’s important to understand that injuries are not accidents. Most injuries are predictable and preventable. Programs can take steps to prevent serious injuries by

- choosing developmentally-appropriate play equipment to ensure children do not fall from a high level and the challenges on the playground are matched with their ability.

- installing proper surfacing to minimize the severity of an injury if a child does fall.

- providing intentional and active supervision by maintaining close proximity to children, especially in places that are high risk for injury from a fall such as the slide or monkey bars).

- encouraging safe behaviors by introducing safety habits to children.

Reinforcing these safe behaviors in an early care and education program provides lifelong lessons about safety and injury prevention. As consultants, you can work with your program and teachers to predict and prevent many injuries and allow children to play.

Use Zones

The use zone is the space that encompasses the activity/piece of equipment and the area around that activity/equipment that will keep children from colliding and provides enough separation between different pieces of equipment and types of play. It is also sometimes referred to as a fall zone. The use zone should be free of movable hazards like trikes and toys, rocks, and groups of children who might cluster and fixed hazards such benches.

Age Appropriateness

Age-appropriate equipment provides children with opportunities to safely practice gross motor skills without putting them at risk for unnecessary injury. This takes us back to the notion of creating playgrounds that are high challenge but low risk.

Children are less likely to fall when equipment is only used with the age group for which it is designed. Equipment that is made according to the ASPM or CPSC standards will clearly be marked with the age group for which it is intended. And that’s usually either 6 to 23 months of age, 2 to 5 years of age, and 5 to 12 years of age. So, any equipment that is marked for 5 to 12 years of age is not acceptable on a preschool playground.20

Table 11.8 – Age-Appropriate Equipment21

|

|

Age |

Age Appropriate Equipment |

|

|

2 to 5 years |

|

|

|

5 to 12 years |

|

|

|

Not appropriate for any age |

|

Hazards on Playgrounds

Gaps in equipment such as the space between the platform and the top of the slide or hooks can entangle clothing or entrap body parts, causing trips, falls, or strangulation. Head entrapment into gaps that are large enough for a child’s body to pass through (bigger than 3.5 inches) but too small for a child’s head to pass through (smaller than 9 inches) can injure a child’s neck or choke a child.

Equipment that spins and moves such as steering wheels or springs on rockers can pinch, cut, or crush fingers or other body parts. So, you want to make sure that any equipment that spins or moves is not accessible for little fingers. Broken parts or improperly installed equipment can cause injuries if the equipment tips over, breaks during use, or has sharp or loose parts that can cut or entrap a child. And railings to prevent falls can break if bolts are loose. See Table 4.5 for examples of dangers to watch for on playgrounds.

Keeping Children Safe by Monitoring

Early care and education programs need to develop a routine inspection process to identify and prevent hazards. Outdoor play spaces are subject to a lot of wear and tear from use, sometimes misuse, from weather conditions. So, even if a program has correctly installed safe and age and developmentally-appropriate equipment, it still requires regular inspections and maintenance.

The outdoor space, including the playground, should be inspected using checklists such as the ones in Appendix E. It should be inspected upon initial installment.

It should also be inspected on a daily basis to identify hazards that may have appeared suddenly. It will also alert staff to any pieces of equipment that may have broken or become worn since last being used. Some general items to include in a daily inspection may include ensuring that

- any broken equipment is removed from children’s access or repaired

- the playground is free from

- glass, needles, cigarette butts, animal feces, and trash

- standing water

- trip hazards

- the use zones are free from obstacles that may have been moved into them, such as tricycles or movable benches

- displaced loose fill surfacing is raked

- platforms and pads are free of sand and surfacing debris and any tripping hazards

- the area is scanned for

- insects or insect nests

- broken equipment

- weather-related hazards such as hot surface or equipment, ice, or other damage from weather

A monthly inspection would include:

- checking for loose or missing hardware, checking

- inspecting equipment for broken parts, splinters, rust, or sharp edges,

- replenishing loose fill surfacing if needed, and

- examining vegetation for hazardous or poisonous plants.

There has to be a system in place to conduct inspections and then respond in a timely manner when something is identified. It’s too common for someone to notice a hazard but to forget to report it or for somebody to report a hazard but then people forget to follow through to correct it. Many checklists include space for writing down a corrective action plan. Once the hazard is identified the person completing the form will write down what steps should be taken to correct the problem, including identifying who will fix it, what needs to be done, and when it will be done. The process should also include a system to check that the problem was fixed in a timely manner.

A record of any injury reported to have occurred on the playground should also trigger an additional inspection of that piece of equipment (this was previously discussed in Chapter 2). This will help identify potential hazards or dangerous design features that should be corrected.

Active Supervision

The most important tool for reducing playground injuries is active supervision (which is also addressed in Chapter 2). Early childhood educator should be actively supervising children at all times. Active supervision is a specific child supervision technique that requires focused attention and intentional observation of children at all times. Active supervision includes six basic strategies.

- Plan and set up the environment to ensure clear sightlines and easy access to the children and the equipment at all times while they’re out on the playground.

- Teachers are positioned among the children in their care, changing positions as needed so that they can keep an eye on the children.

- They are communicating about which children they’re observing and any issues that divert their attention so that they know other teachers are taking up the slack and watching the other children.

- Teachers are watching, counting, and listening to children at all times

- They also use their knowledge of each child’s development and abilities to anticipate what a child might do or to anticipate areas on the playground where a child might need some additional support.

- And if needed, they get involved and they redirect children when necessary or they provide that additional support if needed.28

Figure 11.24: If this teacher is engaging with these two children, she would communicate this so the other teachers could make sure they are effectively supervising the other children outside.

Other Safety Considerations for the Outdoors

In addition to designing and maintaining a safe playground for children, you also need to monitor environmental factors such as weather, the sun, insects, animals, poisonous plants or materials, and water.29 These are discussed in chapter 10.

Pedestrian Safety

Each year for more than a decade, more than 700 children have died from injuries sustained while walking, over 500 of these in traffic. Although the fatality rate has declined somewhat during this period, it could be attributable to improvements in pre-hospital and emergency medical care or to a decline in walking as a mode of transportation. As we want children (and their educators and families) to get out and walk to for both health reasons and for opportunities to explore and learn about their communities, we must make sure that they have a safe environment in which to do so. Children under 10 should always have adult supervision.38

Figure 11.25 – If these children were younger, would they need additional safety considerations?39

Teaching Children about Pedestrian Safety

Before going on a walk, teachers should talk to children about the safety practices that they will be using (see Table 4.7). Children need close adult supervision and proximity while walking because they may do the unexpected (like suddenly dart off the sidewalk).40

Table 11.9 – Safety Practices While Walking,

|

Always walk on the sidewalk (if there is one). |

|

If there is no sidewalk, walk facing traffic. |

|

Be safe and be seen (bright clothing during the day, lights and reflectors at night). |

|

Walk safely. Don’t run, don’t push or roughhouse. Be aware and don’t let toys distract you. |

|

Watch for cars pulling in and out of driveways. Make sure drivers make eye contact with you. |

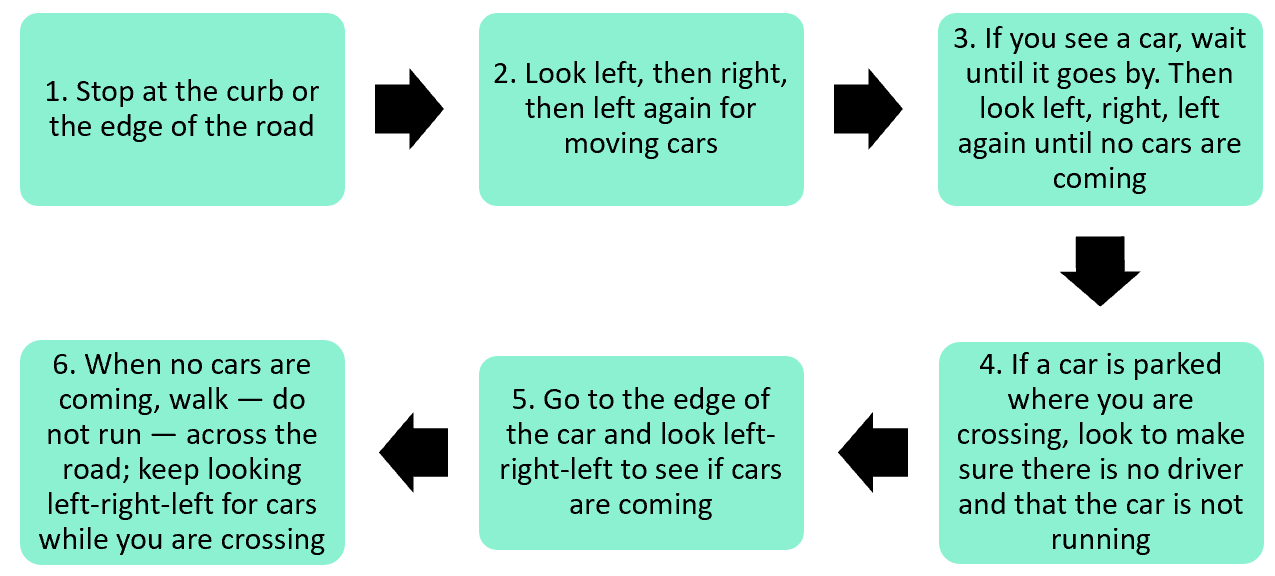

When it is time to cross the street, show children a good place to safely cross the street. Explain how to safely cross the street (see Figure 4.13). If there is a button at the crosswalk, have them push it.45

Figure 11.26 – Steps for Crossing the Road Safely46

Motor Vehicle Safety

Motor vehicle injuries are a leading cause of death among children in the United States. But many of these deaths can be prevented.

- In the United States, 723 children ages 12 years and younger died as occupants in motor vehicle crashes during 2016, and more than 128,000 were injured in 2016.

- One CDC study found that, in one year, more than 618,000 children ages 0-12 rode in vehicles without the use of a child safety seat or booster seat or a seat belt at least some of the time.

- Of the children ages 12 years and younger who died in a crash in 2016 (for which restraint use was known), 35% were not buckled up.

|

|

Hot Car Warning! “Never leave children in a car or in another closed motor vehicle. The temperature inside the car can quickly become much higher than the outside temperature—a car can heat up about 19 degrees in as little as 10 minutes and continue rising to temperatures that cause death.”51 |

Tips for Safe Field Trips

Early care and education programs can be enriched through carefully planned field trips. It is important that the destination be appropriate for the age and developmental level of each child that will be attending. Any special arrangements needed to make sure that all children can safely be included should be made ahead of time.

All staff and background-checked volunteers that will be attending should be made familiar with the travel plans, the field trip location, rules, and their responsibilities. The children should also be prepared for the trip. Teachers can review and practice safety precautions and emergency procedures.

Families should be made aware of the field trip and provide consent for their child to attend. Emergency information for every child should be kept with staff off-site at all times. An accurate list of all children in attendance must be kept as well (at the field trip destination and at the school/center).

Adults should be assigned small groups of children. All adults should be made aware of the chosen regrouping location and checkpoints. Information is also provided in Chapter 6 about preventing lost children on field trips.55

|

|

Risky Play and Children’s Safety: Balancing Priorities for Optimal Child DevelopmentInjury prevention plays a key role in promoting children’s safety, which is considered to involve keeping children free from the occurrence or risk of injury. However, emerging research suggests that imposing too many restrictions on children’s outdoor risky play may be hampering their development. Like safety, play is deemed so critical to child development and their physical and mental health that it is included in Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Thus, limitations on children’s play opportunities may be fundamentally hindering their health and well-being. Eager and Little describe a risk deprived child as more prone to problems such as obesity, mental health concerns, lack of independence, and a decrease in learning, perception and judgment skills, created when risk is removed from play and restrictions are too high. Findings from disciplines such as psychology, sociology, landscape architecture, and leisure studies, challenge the notion that child safety is paramount and that efforts to optimize child safety in all circumstances is the best approach for child development. And families, popular culture, the media, and researchers in other disciplines have expressed views that child safety efforts promote the overprotection of children. These have the potential to trigger a backlash against proven safety promotion strategies, such as child safety seats or necessary supervision, possibly reversing the significant gains that have been made in reducing child injuries. Families, caregivers, and educators can work to create a balance by fostering opportunities to engage in outdoor risky play that align with safety efforts. An approach that focuses on eliminating hazards, that have hidden potential to injure, such as a broken railing, but that does not eliminate all risks, could be used. This allows the child to recognize and evaluate the challenge and decide on a course of action that is not dangerous but may still involve an element of risk. Adults can also provide children with unstructured (open-ended) play materials that can be freely manipulated in conventional playgrounds

This is an example of an adventure playground.38 This approach is a central component of the Adventure Playground movement. Notably, European and Australian organizations and researchers appear to be attempting to put this idea in practice, with North American efforts lagging. For example, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence in the U.K. released injury prevention guidelines that called for policies that counter “excessive risk aversion” and promote children’s need “to develop skills to assess and manage risks, according to their age and ability.” Both injury and play organizations, such as the U.K.’s Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents and Play Safety Forum promote the idea of keeping children as safe as necessary, not as safe as possible. International collaboration would benefit from translating this into practice in a manner that is sensitive to concerns for child safety and children’s developmental needs for risky play.39 |

A note about risky play from a former FSW student:

Risky play

In addition to risky play, messy sensory play also has many benefits for young children. Find tips and ideas for mud play here.

|

|

Pause to ReflectWhat do you think? What are your thoughts about keeping children as safe as necessary, not as safe as possible? What are appropriate ways for children to learn how to manage risk? |

Specific Risks for Injury

Child injuries are preventable, yet 8,110 children (from 0-19 years) died from injuries in the US in 2017.14 Car crashes, suffocation, drowning, poisoning, fires, and falls are some of the most common ways children are hurt or killed. The number of children dying from injury dropped nearly 30% over the last decade. However, injury is still the number 1 cause of death among children.15

Children during early childhood are more at risk for certain injuries. Using data from 2000-2006, the CDC determined that:

- For children less than 1 year of age, two–thirds of injury deaths were due to suffocation.

- Drowning was the leading cause of injury death between 1 and 4 years of age.

- Falls were the leading cause of nonfatal injury for all age groups of less than 15 years of age.

- For children ages 0 to 9, the next two leading causes were being struck by or against an object and animal bites or insect stings.

- Rates for fires or burns and drowning were highest for children 4 years and younger.16

Injury in Early Care and Education/Child Care

Families “are naturally concerned for their child’s safety, particularly when cared for outside of the home. However, children who spend more time in nonparental child care have a reduced risk of (unintentional) injury. This may be because child care centers and family day homes provide more supervision and/or safer play equipment. Nevertheless, injuries in child care settings remain a serious, but preventable, health care issue.”17

In the next two chapters, we will examine creating safe environments indoors and outdoors that specifically reduce the risks of injuries, including those introduced in Table 2.2.

Table 11.10 – Preventing Injuries

|

Type of Injury |

Prevention Tips |

|

Sudden Infant Death |

Always put infants to sleep on their backs Cribs, bassinets, and play yards should conform to safety standards and covered in a tight-fitting sheet There should be no fluffy blankets, pillows, toys, or soft objects in the sleeping area Don’t allow children to overheat18 |

|

Choking |

Keeping objects smaller than 1½ inches out of reach of infants, toddlers, and young children. Have children stay seated while eating Cut food into small bites Ensure children only have access to age-appropriate toys and materials19, 20 |

|

Drowning |

Make sure caregivers are trained in CPR Fence off pools; gates should be self-closing and self-latching Supervise children in or near water Inspect for any standing water indoors or outdoors that is an inch or deeper. Teach children water safety behaviors.22 |

|

Burns |

Have working smoke alarms Practice fire drills Never leave food cooking on the stove unattended; supervise any use of microwave Make sure the water heater is set to 120 degrees or lower Keep chemicals, cleaners, lighters, and matches securely locked and out of reach of children. Use child-proof plugs in outlets and supervise all electrical appliance usage.24 |

|

Falls |

Make sure playground surfaces are safe, soft, and made of impact-absorbing material (such as wood chips or sand) at an appropriate depth and are well maintained Use safety devices (such as gates to block stairways and window guards) Make sure children are wearing protective gear during sports and recreation (such as bicycle helmets) Supervise children around fall hazards at all times Use straps and harnesses on infant equipment.26 |

|

Poisoning |

Lock up all medications and toxic products (such as cleaning solutions and detergents) in original packaging out of sight and reach of children Know the number to poison control (1-800-222-1222) Read and follow labels of all medications Safely dispose of unused, unneeded, or expired prescription drugs and over the counter drugs, vitamins, and supplements Use safe food practices. |

|

Pedestrian |

Do not allow children under 10 to walk near traffic without an adult Increase the number of supervising adults when walking near traffic Teach children about safety including: Walking on the sidewalk Not assuming vehicles see you or will stop Crossing only in crosswalks Looking both ways before crossing Never playing in the road Not crossing a road without an adult Supervise children near all roadways and model safe behavior |

Creating a Safety Plan

Early care and education programs have an obligation to ensure that children in their care are in healthy and safe environments and that policies and procedures that protect children are in place. Using a screening tool, programs can identify where they need to make changes and improvements to ensure children are healthy and safe while in their care. A checklist such as the one modified from Head Start’s Health and Safety Screener in Appendix C can be used for this purpose.30

Figure 11.29– Early childhood programs can make a safety plan.31

Programs must become familiar with the hazards to children that are specific to their population and location. Considerations for this plan include the type of early education program, ages of the children served, surrounding community, and family environments.

If any hazards are found upon screening, programs can make modifications to remove hazards or use safety devices to protect children from hazards. Care should be taken to ensure that the modifications include children with disabilities and special needs.

It will also be important to use positive guidance to help modify behaviors that put children’s safety at risk. Teachers can use role-modeling and communication to teach children how to respond to situations, including emergencies, that put their safety at risk.

Early childhood programs must continue to monitor for safety. This includes regular screening for safety and analysis of data surrounding injuries. Teachers must continuously monitor for conditions that may lead to children being injured and examine both the behaviors of children and adults in the environment.32

Documenting Injuries & Injury Prevention

When a child is injured, it is important to document the injury. This documentation is provided to families, typically in the form of an injury or incident report. See Appendix D for an example injury/incident report form. These should document:

- Who was involved in each injury? (child/children; staff, volunteers, family members)

- Where did the injury occur?

- What happened? (What was the cause?)

- What was the severity of each injury?

- When did each injury occur?

- Who – e.g., what staff were present and where were they at the time of each injury?

- What treatment was provided? How was the incident handled by staff?

- How could each injury have been prevented? What will be done in the future to prevent similar injuries?

- Who was notified in the child’s family? When? How?

It is important to keep these reports to analyze them to:

- identify location(s) for high risk of injury.

- pinpoint systems and services that need to be strengthened.

- develop corrective action plans

- incorporate safety and injury prevention into ongoing-monitoring activities.33

Hazard Mapping

One such process to do this is hazard mapping, which is an approach to prevent injuries by studying patterns of incidents.

Step One – Identify High-Risk Injury Locations

- Create a map of the classroom, center, or playground area. Label the various places and/or equipment in the location(s) that is being mapped. Make the map as accurate as possible.

- Place a “dot” or “marker” on the map to indicate where each specific incident and/or injury occurred over the past 3-6 months (or sooner, if concerns arise).

- Look at the severity of the injuries.

- Identify where most incidents occur.

Step Two – Identify Systems and Services that Need to be Strengthened

- Review the information on the injury/incident reports for areas with multiple dots.

- Consider what policy and practices are contributing to injuries/incidents.

Step Three – Develop a Corrective Action Plan

- Prioritize and select specific activities/strategies to resolve problem areas.

- Develop an action plan to correct the problem areas you identified. Include each of the activities/strategies selected in this corrective action plan. Identify the steps, the individuals responsible, and the dates for completion.

- Create a plan for sharing the corrective action plan with staff and families.

Step Four – Incorporate Hazard Mapping into Ongoing Monitoring

- Determine if any additional questions should be added to injury/incident report forms to obtain this missing information.

- When developing corrective action plans, consider prioritizing more serious injuries, even if they have occurred less often.

- Make sure there reduction in injuries and/or incidents and the severity of the injuries with a corrective plan.34

Summary

Safe, outdoor play is vital to children’s health and well-being. Environments that are well designed, with age appropriate, hazard-free equipment, impact absorbing surfaces, and use zones around equipment will protect children from many injuries. Supervising children and actively monitoring the outdoor space are also key to preventing injuries. Having knowledge about the weather, implementing sun safety practices, protecting children from insects, following safe practices around water play, and storing toys safely are also important for children’s safety. When going off site (and during drop off and pick up times), it’s important to remember pedestrian safety and how to safely transport children in motor vehicles.

Teachers need to create safe indoor environments in which children engage, explore, and interact. By recognizing that behavior is communication, they can help children use safe behaviors to get their needs met. Teachers should choose age-appropriate toys and materials that are well constructed, hazard-free, and nontoxic. With adult support, children can navigate media and technology safely. Teachers must work to prevent injuries that may occur indoors, such as choking, poisoning, burns, drowning, and falls.

|

|

Resources for Further Exploration

|

|

|

Resources for Further Exploration

|