5 Chapter Five: Prevention of Illness

Kelly McKown

Chapter 5 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe each of the five ways illness is transmitted.

- Explain how immunization prevents illness.

- Identify standard precautions to prevent illness.

- Discuss practices to protect children from environmental hazards.

- Identify symptoms of infectious disease that is common during early childhood.

- Outline criteria for exclusion from care for ill children and staff.

- Describe considerations programs must make regarding caring for children that are mildly ill.

- Recall licensing requirements for handling medication in early care and education programs.

- Explain the communication about illness that should happen between families and early care and education programs.

Introduction

Science and experience tell us that infectious disease, especially gastrointestinal disease, which means vomiting and diarrhea, and respiratory disease, including coughs, colds, sore throats, and runny noses, are increased among children who are cared for in out-of-home group settings. In addition, such children may be at increased risk for certain other infections that may be transmitted by insects or by body fluids. It’s also true that children who are cared for in group out-of-home settings are more likely to experience infectious illnesses that are more severe and more prolonged (although 90% of those infections are mild and self-limited, requiring no special treatment).

But there’s good news, too. Infectious illnesses such as pneumonia and influenza, which together were the leading causes of death among U.S. children in the early 20th century, have declined 99.7 percent. Common childhood illnesses such as diphtheria, whooping cough, measles, mumps, and rubella are rare except in communities where immunization rates are low, and polio is unheard of in our country today.

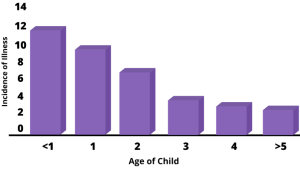

Although younger children are more susceptible to infectious illness because their immune systems are immature, as they grow older, the incidents of infectious disease decreases as their immune systems mature. Furthermore, children who experience more infectious disease at an early age in group out-of-home care have a decreasing incidence of infectious disease as they grow older. In fact, they have less infectious illnesses in kindergarten than children who were taken care of exclusively at home. Illness also decreases with years of attendance in out-of-home early care and education settings.

There are negative consequences of childhood illness, including:

- It’s unpleasant to be sick (for children or the adults that may also become infected).

- Illnesses that are minor in children can be much more serious for adults and pregnant women.

- Some illnesses have severe effects (and can even be life-threatening).

- There are short-term medical costs.

- There may also be additional child care costs or lost wages for parents/caregivers of children that must be excluded from group care.

- Overuse of antibiotics in an effort to get children well contributes to antibiotic resistance among common bacteria.

To prevent illness we need to understand the different ways illness is spread, how immunizations protect children, and what universal precautions early care and education program staff can take to prevent the spread of illness.

How Illnesses are Transmitted

Bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites that cause illness can be transmitted in five ways, including through:

- the respiratory route

- the fecal-oral route

- the direct contact route

- the bodily fluid route (including blood, urine, vomit, and saliva)

- the vector-borne route

Respiratory Transmission

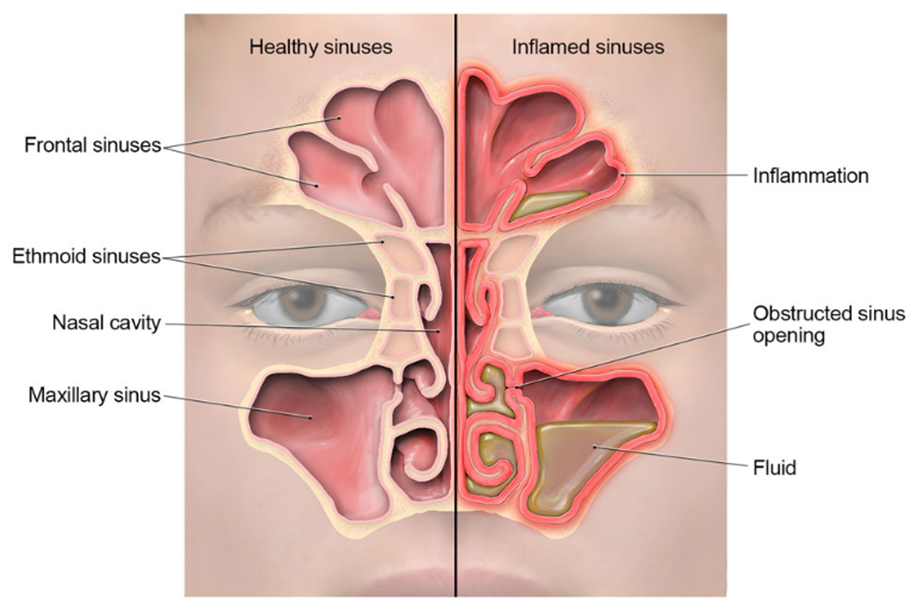

Most respiratory germs stay in the nose, sinuses, mouth and throat, or possibly the middle ear. Upper respiratory illnesses (colds) are the most common and the most likely to be transmitted in early care and education settings.

The more common respiratory illnesses include:

- Sinusitis

- Sore throat

- Common cold

- Recurrent middle ear infection

- Strep throat

- RSV

- Pneumonia

- Bronchitis

Pneumonia and bronchitis are rarely the result of an infection picked up in an early education setting. We also have immunizations for many respiratory diseases that are rarely transmitted in early care and education settings today, including:

- Mumps

- Measles

- Bacterial meningitis

- Chicken pox

- Diphtheria

- Pertussis

- Pneumonia

- Seasonal flu

If we could actually see what comes out of a child’s mouth along with a cough or a sneeze, we might appreciate the respiratory route of infectious disease transmission more.

The germs that are in this contaminated cloud of exhalation can wind up on surfaces and hands and be transmitted to others. Staff and children who are able to are encouraged to cough into their sleeves. Covering your mouth with your hand only transfers these germs to your hand. This will be addressed more in depth later in the chapter.

Fecal-Oral Transmission

When organisms that live in our intestines get into our mouths they can cause illness. Usually, this happens via someone’s hands, usually our own. Fecal-oral routes diseases include:

- Hepatitis A

- diarrhea

- hand, foot, and mouth disease

- pinworms

- rotavirus

- norovirus

- giardia

- shigella

- cryptosporidiosis

That is why it is so important that everyone wash hands after using the bathroom, changing diapers, when preparing food, and before eating.

Food Poisoning

- coli and salmonella are two of the germs that you may also have heard mentioned in the news when grocery stores send back fresh vegetables, meat, or poultry. These organisms originate with farm animals themselves and they can cause diarrhea and vomiting if children or staff eat contaminated food. Properly preparing and serving fresh produce, meat, and poultry is essential to prevent food poisoning.

Direct Contact Transmission

Direct contact with another person’s skin (or hair) puts infants and children at risk of illnesses such as:

- cold sores

- conjunctivitis

- pink eye

- impetigo

- lice

- scabies

- ringworm (a fungus, not a worm).

Bodily Fluid Transmission

Bodily fluids, including saliva, urine, vomit, and blood, can cause illness, such as:

- Dental caries (by saliva)

- Cytomegalovirus or CMV (by urine)

- Hepatitis B (preventable by vaccine)

- Hepatitis C (rare in children)

- HIV (no cases of transmission in an early education setting)

Vector-Borne Transmission

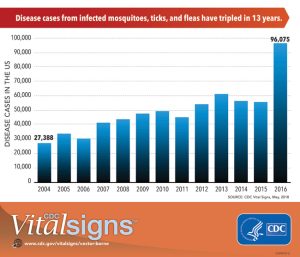

A vector is a living thing that can transmit disease. We know, for example, that ticks can transmit Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Fleas are known to transmit Bubonic plague and typhus. Mosquitoes can infect people with St. Louis encephalitis (SLE), dengue fever, Zika virus, and West Nile disease. Rats and mice can transmit leptospirosis, trichinosis, hantavirus, and bacterial food poisoning. Raccoons can spread raccoon roundworm.

While these illnesses are relatively uncommon, the risk reminds us of the importance of

- utilizing integrated pest management techniques to keep insects and rodents out of buildings (covered later in this chapter)

- using insect repellant specifically recommended for children during outdoor activities

- removing standing water in which mosquitoes can lay their eggs

- checking for and removing ticks (addressed in Figure 4.10) in centers when children come back in after playing in or near heavily wooded areas[4]

Pause to Reflect

| Why is it important to understand how illnesses and diseases are spread? |

Immunizations

Prevention of infectious disease starts with immunizations (or vaccines). Immunizations are considered the number one public health intervention of the 20th century and one of the top 10 interventions of the first decade of the 21st century.[5]

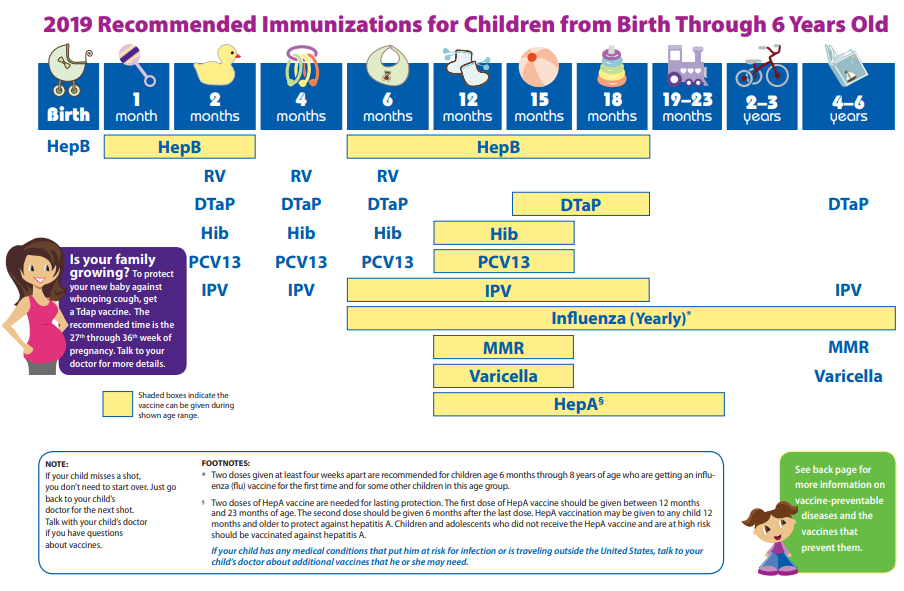

On-time vaccination throughout childhood is essential because it helps provide immunity before children are exposed to potentially life-threatening diseases. Vaccines are tested to ensure that they are safe and effective for children to receive at the recommended ages.[6] See Figure 8.X for the current schedule of immunizations.

Fully vaccinated children in the U.S. are protected against sixteen potentially harmful diseases (see Figure 8.X). Vaccine-preventable diseases can be very serious, may require hospitalization, or even be deadly — especially in infants and young children.[7]

Here is the schedule from the CDC to ensure a child is fully vaccinated:

The current schedule of vaccines (see Figure 8.6) protects children from the illnesses listed in Table 8.1)

Table 5.1 – Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. [9]

| Disease | Vaccine | Disease Spread By | Disease Symptoms | Disease Complications |

| Chick-pox | Varicella vaccine protects against chick pox | Air, direct contact

|

Rash, tiredness, headache, fever

|

Infected blisters, bleeding disorders, encephalitis (brain

swelling), pneumonia (infection in the lungs) |

| Diphtheria | DtaP* vaccine protects against diphtheria | Air, direct contact

|

Sore throat, mild fever, weakness, swollen

glands in neck |

Swelling Of the heart muscle, heart failure, coma, Paralysis, death |

| HiB | Hib vaccine protects against Haemophilus

Influenza type b |

Air, direct contact

|

May be no symptoms unless bacteria

enter the blood

|

Meningitis (infection of the covering around the brain

and spinal cord), intellectual disability. epiglottitis (life-threatening infection that can block the windpipe And lead to serious breathing problems), pneumonia (infection in the lungs), death

|

| Hepatitis A | HepA vaccine protects against hepatitis A. | Direct contact, contaminated

food or water

|

May be no symptoms – fever, stomach pain,

loss of appetite. Fatigue, vomiting, jaundice (yellowing of skin and eyes). dark urine |

Liver failure. arthralgia (joint pain), kidney, pancreatic,

and blood disorders

|

| Hepatitis B | HepB vaccine protects against hepatitis B. | Contact With

body fluids

|

May be no symptoms fever, headache,

weakness, vomiting, jaundice (yellowing of skin and eyes), joint pain

|

Chronic liver infection, liver failure, liver cancer

|

| Influenza (Flu) | Flu vaccine protects against influenza.

|

Air, direct contact

|

Fever, muscle pain, sore throat, cough,

extreme fatigue

|

Pneumonia (infection in the lungs)

|

| Measles | MMR* vaccine protects against measles.

|

Air, direct contact

|

Rash, fever, tough, runny nose, pinkeye

|

Encephalitis (brain swelling), pneumonia (infection in

the lungs). death

|

| Mumps | MMR* vaccine protects against mumps.

|

Air, direct contact

|

Swollen salivary glands (under the jaw), fever,

headache, tiredness, muscle pain |

Meningitis (infection of the covering around the brain

and spinal cord) , encephalitis (brain swelling), inflammation Of testes or ovaries, deafness

|

| Pertussis

|

DTap* vaccine protects against pertussis

(whooping cough).

|

Air, direct contact

|

Severe cough, runny nose, apnea (a pause in

breathing in infants) |

Pneumonia (infection in the lungs), death

|

| Polio | IPV vaccine protects against polio.

|

Air. direct contact, through

the mouth

|

May be no symptoms, sore throat, fever,

nausea. headache

|

Paralysis, death

|

| Pneumococcal

|

POII 3 vaccine protects against pneumococcus. | Air, direct contact

|

May be no symptoms -. pneumonia (infection

in the lungs)

|

Bacteremia (blood infection), meningitis (infection of

the covering around the brain and spinal cord). death

|

| Rotavirus | RV vaccine protects against rotavirus.

|

Through the mouth | Diarrhea, fever, vomiting

|

Severe diarrhea, dehydration

|

| Rubella | MMR* vaccine protects against rubella.

|

Air, direct contact

|

Children infected with rubella virus sometimes

have a rash, fever. swollen nodes |

Very serious in pregnant women—can lead to miscarriages, stillbirth, premature delivery, birth defects

|

| Tetanus | DTap* vaccine protects against tetanus.

|

Exposure through cuts in skin

|

Stiffness in neck and muscles,

difficulty swallowing, muscle spasms, fever |

Broken bones, breathing difficulty, death

|

How Vaccines Work

The immune system helps the human body fight germs by producing substances to combat them. Once it does, the immune system “remembers” the germ and can fight it again. Vaccines contain germs that have been killed or weakened. When given to a healthy person, the vaccine triggers the immune system to respond and thus build immunity.

Before vaccines, people became immune only by actually getting a disease and surviving it. Immunizations are an easier and less risky way to become immune.

Vaccines are the best defense we have against serious, preventable, and sometimes deadly contagious diseases. Vaccines are some of the safest medical products available, but like any other medical product, there may be risks. Accurate information about the value of vaccines as well as their possible side effects helps people to make informed decisions about vaccination.

Potential Side Effects

Vaccines, like all medical products, may cause side effects in some people. Most of these side effects are minor, such as redness or swelling at the injection site. Read further to learn about possible side effects of vaccines.

Any vaccine can cause side effects. For the most part, these are minor (for example, a sore arm or low-grade fever) and go away within a few days.[10] Serious side effects after vaccination, such as severe allergic reaction, are very rare.[11]

Remember, vaccines are continually monitored for safety, and like any medication, vaccines can cause side effects. However, a decision not to immunize a child also involves risk and could put the child and others who come into contact with him or her at risk of contracting a potentially deadly disease.

How Well Do Vaccines Work?

Vaccines work really well. No medicine is perfect, of course, but most childhood vaccines produce immunity about 90–100% of the time.

What about the argument made by some people that vaccines don’t work that well and that diseases would be going away on their own because of better hygiene or sanitation, even if there were no vaccines?

That simply isn’t true. Certainly better hygiene and sanitation can help prevent the spread of disease, but the germs that cause disease will still be around, and as long as they are they will continue to make people sick.

All vaccines must be licensed (approved) by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before being used in the United States, and a vaccine must go through extensive testing to show that it works and that it is safe before the FDA will approve it. Among these tests are clinical trials, which compare groups of people who get a vaccine with groups of people who get a control. A vaccine is approved only if FDA makes the determination that it is safe and effective for its intended use.

If you look at the history of any vaccine-preventable disease, you will virtually always see that the number of cases of disease starts to drop when a vaccine is licensed. Vaccines are the most effective tool we have to prevent infectious diseases.

Opposition to Vaccines

In 2010, a pertussis (whooping cough) outbreak in California sickened 9,143 people and resulted in 10 infant deaths: the worst outbreak in 63 years (Centers for Disease Control 2011b). Researchers, suspecting that the primary cause of the outbreak was the waning strength of pertussis vaccines in older children, recommended a booster vaccination for 11–12-year-olds and also for pregnant women (Zacharyczuk 2011). Pertussis is most serious for babies; one in five needs to be hospitalized, and since they are too young for the vaccine themselves, it is crucial that people around them be immunized (Centers for Disease Control 2011b). Several states, including California, have been requiring the pertussis booster for older children in recent years with the hope of staving off another outbreak.

But what about people who do not want their children to have this vaccine, or any other? That question is at the heart of a debate that has been simmering for years. Vaccines are biological preparations that improve immunity against a certain disease. Vaccines have contributed to the eradication and weakening of numerous infectious diseases, including smallpox, polio, mumps, chickenpox, and meningitis.

However, many people express concern about the potential negative side effects of vaccines. These concerns range from fears about overloading the child’s immune system to controversial reports about devastating side effects of the vaccines.[13]

Although children continue to get several vaccines up to their second birthday, these vaccines do not overload the immune system. Every day, an infant’s healthy immune system successfully fights off thousands of antigens – the parts of germs that cause their immune system to respond. Even if your child receives several vaccines in one day, vaccines contain only a tiny amount of antigens compared to the antigens your baby encounters every day.

This is the case even if your child receives combination vaccines. Combination vaccines take two or more vaccines that could be given individually and put them into one shot. Children get the same protection as they do from individual vaccines given separately—but with fewer shots.[14]

One misapprehension is that the vaccine itself might cause the disease it is supposed to be immunizing against.[15] Vaccines help develop immunity by imitating an infection, but this “imitation” infection does not cause illness. Instead, it causes the immune system to develop the same response as it does to a real infection so the body can recognize and fight the vaccine-preventable disease in the future. Sometimes, after getting a vaccine, the imitation infection can cause minor symptoms, such as fever. Such minor symptoms are normal and should be expected as the body builds immunity.[16]

Another commonly circulated concern is that vaccinations, specifically the MMR vaccine (MMR stands for measles, mumps, and rubella), are linked to autism. The autism connection has been particularly controversial. In 1998, a British physician named Andrew Wakefield published a study in Great Britain’s Lancet magazine that linked the MMR vaccine to autism. The report received a lot of media attention, resulting in British immunization rates decreasing from 91 percent in 1997 to almost 80 percent by 2003, accompanied by a subsequent rise in measles cases (Devlin 2008). A prolonged investigation by the British Medical Journal proved that not only was the link in the study nonexistent, but that Dr. Wakefield had falsified data in order to support his claims (CNN 2011). Dr. Wakefield was discredited and stripped of his license, but the doubt still lingers in many parents’ minds.

In the United States, many parents still believe in the now-discredited MMR-autism link and refuse to vaccinate their children. Other parents choose not to vaccinate for various reasons like religious or health beliefs. In one instance, a boy whose parents opted not to vaccinate returned home to the U.S. after a trip abroad; no one yet knew he was infected with measles. The boy exposed 839 people to the disease and caused 11 additional cases of measles, all in other unvaccinated children, including one infant who had to be hospitalized.

According to a study published in Pediatrics (2010), the outbreak cost the public sector $10,376 per diagnosed case. The study further showed that the intentional non-vaccination of those infected occurred in students from private schools, public charter schools, and public schools in upper-socioeconomic areas (Sugerman et al. 2010).[18]

What about the Flu Vaccine?

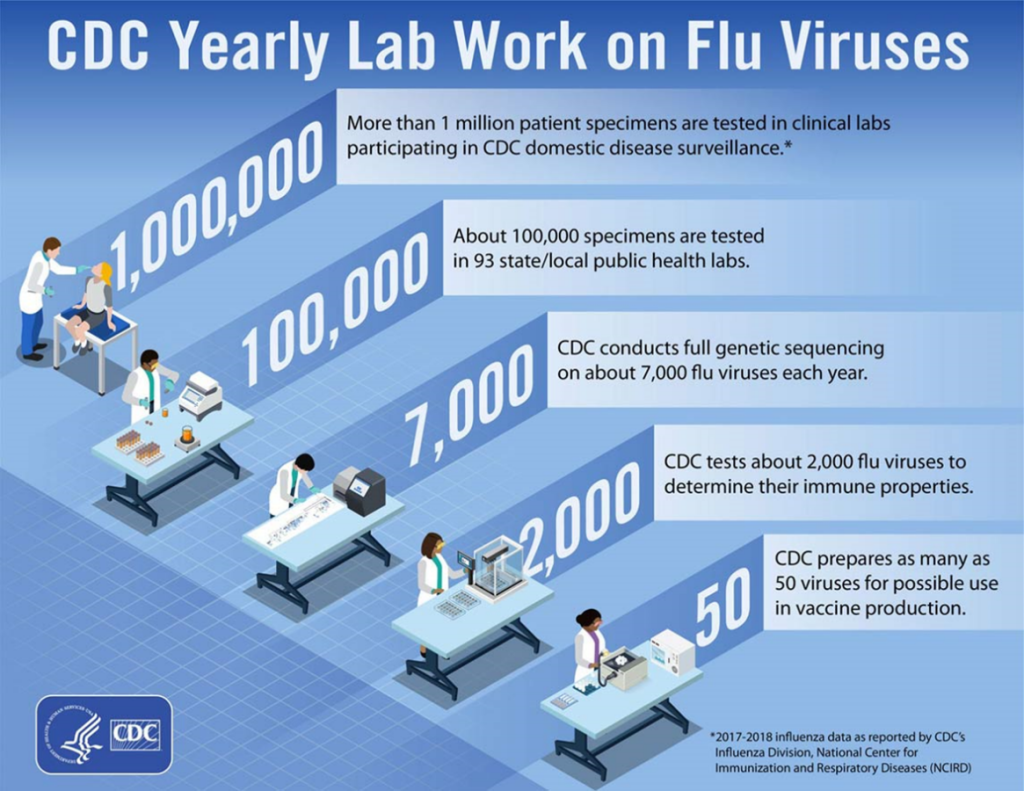

There are many reasons to get an influenza (flu) vaccine each year. Below is a summary of the benefits of flu vaccination, and selected scientific studies that support these benefits.

· Flu vaccination can keep you from getting sick with flu.

· Flu vaccination can reduce the risk of flu-associated hospitalization.

· Flu vaccination is an important preventive tool for people with chronic health conditions.

· Flu vaccination helps protect women during and after pregnancy and helps protect the baby from flu for several months after birth.

· Flu vaccination can be life-saving in children.

· Flu vaccination has been shown in several studies to reduce the severity of illness in people who get vaccinated but still get sick.

· Getting vaccinated yourself may also protect people around you, including those who are more vulnerable to serious flu illness, like babies and young children, older people, and people with certain chronic health conditions.[19]

Pause to Reflect

| Using the information that has been provided about immunizations, think of ways you could respond to the following:

1. “I don’t believe in giving all of the vaccines, like chicken pox. It’s better for children to just get the disease like we all did when we were kids.” 2. “Why do they have to give vaccines so early? It seems like it’s too much, too quickly.” 3. “I have heard that vaccines give some kids autism. And even if they don’t, the side effects are just too scary.” |

Universal Precautions to Prevent the Spread of Illness

There are some standard practices that prevent, or reduce the risk of, the spread of illness in early care and education programs. These are modeled after practices in health care, where everyone is treated as being potentially infected with something that is contagious. Many illnesses are actually contagious before the infected person is symptomatic, so waiting until you see signs of illness is an ineffective way of preventing its spread. Child care providers can practice these four things to help control the spread of illness.

- Hand washing

- Use of disposable nonporous gloves when working with bodily fluids

- Disinfecting potentially contaminated surfaces

- Proper disposal of potentially contaminated waste[21]

Handwashing

Regular handwashing is an important step to minimizing the spread of germs. Hands pick up germs from all of the things they touch and then spread them from one place to another. Germs that are on hands can also enter the body when a person eats or when they touch their eyes, nose, mouth, or any area on the body where the skin is broken (because of a cut, rash, etc.).

All that is needed for handwashing is soap and clean, running water. Handwashing with soap and water removes visible dirt and hidden germs. Studies have demonstrated that handwashing reduced the number of diarrheal illnesses by 31 percent and respiratory illnesses by 21 percent.

Hands should be washed:

- before eating, feeding, or preparing food. This prevents germs from getting into the mouth from hands. (Hygiene practices related specifically to food safety will be addressed in Chapter 15.)

- after touching saliva (after feeding or eating), mucus (wiping a nose, using a tissue), bodily fluids (toileting, diapering), food, or animals

- when visibly dirty, after touching garbage, or after cleaning

The Center for Disease Control recommends the following handwashing steps:

- “Wet your hands with clean, running water (warm or cold) and apply soap.”

- “Rub your hands together to make a lather and scrub your hands well; be sure to scrub the backs of your hands, between your fingers, and under your nails.”

- “Continue rubbing your hands for at least 20 seconds. Need a timer? Hum the “Happy Birthday” song from beginning to end twice.”

- “Rinse your hands well under running water.”

- “Dry your hands using a clean towel or air dry them.”

Infants and young children will need help with handwashing. Caring for Our Children recommends that caregivers:

- Safely cradle an infant in one arm to wash their hands at a sink.

- Provide assistance with handwashing for young children that cannot yet wash their hands independently.

- Offer a stepping stool to young children so they may safely reach the sink.[23]

Wearing Disposable Gloves

Teachers and caregivers should wear gloves when they anticipate coming into contact with any of the following (on a child’s body or a contaminated surface)

- Blood or bodily substances (i.e., fluids or solids)

- Mucous membranes (e.g., nasal, oral, genital area)

- Non-intact skin (e.g., rashes or cuts and scrapes)[24]

Once the gloves are soiled, it’s important to remove them carefully.

- Using a gloved hand, grasp the palm area of the other gloved hand and peel off the first glove.

- Hold the removed glove in the gloved hand.

- Slide fingers of the ungloved hand under the remaining glove at the wrist and peel off the second glove over the first glove.

- Discard the gloves in a waste container.[25]

After you remove your gloves you should wash your hands. “Do not reuse the gloves: this can spread germs from one child to another…Gloves provide added protection from communicable disease only if used correctly. If you use gloves incorrectly, you actually risk spreading more germs than if you don’t use gloves at all. Pay attention to your gloving technique so that you do not develop a false sense of security (and carelessness) when wearing gloves.”[27]

Cleaning and Disinfecting

Washing Surfaces Germs spread onto surfaces from hands and objects (tissues or mouthed toys) or from a sneeze or cough. It is important to clean all surfaces well, including toys and any surface that a young child puts in his mouth, because germs cannot be seen and it is easy to overlook surfaces that do not look soiled or dirty.

Toileting and diapering involve germs from bodily fluids and fecal material. These germs spread easily in a bathroom onto hands, flushers, and faucets. Routinely washing bathroom surfaces removes most germs and prevents them from spreading. The kitchen is another area of the home where it is important to clean surfaces well.

The terms “cleaning,” “sanitizing,” and “disinfecting” deserve close attention.

Cleaning removes visible soil, dirt, and germs. Soap and water will clean most surfaces.

Sanitizing reduces, but does not totally get rid of, germs to a level that is unlikely to cause disease. Sanitizers may be appropriate to use on surfaces where you eat (such as a table or high chair tray) and with toys that children place in their mouths. It is important to follow the instructions on the label, which may also include rinsing surfaces after using the sanitizing product.

Disinfecting destroys or inactivates infectious germs on surfaces. Disinfectants may be used on diaper-changing tables, toilets, and counter tops.[28]

Early care and education programs can create a bleach and water solution of one tablespoon household bleach to one quart water for surfaces that need to be sanitized or disinfected. To use effectively, the surface must be wetted with the solution and allowed to air dry. A fresh bleach solution should be made each day to maintain effectiveness, and stored in a clearly labeled spray bottle out of children’s reach. Research shows that other chemicals (e.g., ammonia, vinegar, baking soda, Borax) are not effective against some bacteria.[29] “Items that can be washed in a dishwasher or hot cycle of a washing machine do not have to be disinfected because these machines use water that is hot enough for a long enough period of time to kill most germs.”[30]

Cleaning and disinfecting are essential. Studies have shown that some germs, including influenza virus, can survive on surfaces for two to eight hours; rotavirus can survive up to 10 days.[31]

Table 5.2 – Schedule for Cleaning and Disinfecting [32]

| Surface/Item | Clean | Disinfect | Frequency |

| Countertops and Tabletops | X | X | Daily and when soiled |

| Food prep and service areas | X | X | Before and after use; between prep of raw and cooked food |

| Floors | X | X | Daily and when soiled |

| Door and cabinet handles | X | X | Daily and when soiled |

| Carpets and large rugs | X | Vacuum daily; clean monthly for infants, every 3 months for other ages and when soiled | |

| Small rugs | X | Shake or vacuum daily; launder weekly | |

| Utensils, surfaces, and toys that go in the mouth or have been in contact with bodily fluids | X | X | After each child’s use |

| Toys not contaminated with bodily fluids | X | Weekly | |

| Dress up clothes not worn on the head | X | Weekly | |

| Hats | X | After each child’s use | |

| Sheets and pillowcases | X | Weekly and when visibly soiled | |

| Blankets and sleeping bags | X | Monthly and when visibly soiled | |

| Cubbies | X | Weekly | |

| Cribs | X | Weekly | |

| Handwashing sinks including faucet, soap dispenser, and surrounding area | X | X | Daily or when soiled |

| Toilet seats, handles, door knobs or handles in toileting area, floors | X | X | Daily and immediately is soiled |

| Toilet bowls | X | X | Daily |

| Changing tables | X | X | After each child’s use |

| Potty chairs (discouraged in child care because of contamination risks) | X | X | After each child’s use |

| Any surface contaminated with bodily fluids (saliva, mucus, vomit, urine, stool, or blood) | X | X | Immediately |

| Water containers | X | X | Daily |

Disposal of Waste

Proper disposal and storage of garbage waste prevent the spread of disease, odors, and problems with pests. Disposable items (diapers, gloves, paper towels, and facial tissues) should be thrown away immediately in an appropriate container. Make sure the container is water and rodent-proof, operated with a foot pedal, is lined with a plastic bag, within reach of diaper changing area, handwashing sink, and food preparation areas, out-of-reach of and unable to be knocked over by infants and toddlers. The containers should be emptied, cleaned, and sanitized daily. [33]

Pause to Reflect

| You are at a job interview to become a teacher in an infant room and the director asks you what you would do to prevent the spread of illness in your classroom. What might you want to mention? |

Environmental Health

Sometimes the threat to health comes from the environment itself. Air quality, chemical hazards, drinking water, mold, and pest management are all topics early care and education providers should be aware of.

Outdoor Air Quality

Children are more susceptible to the effects of contaminated air because they breathe in more oxygen relative to their body weight than adults.[37] Therefore, they “can be exposed to a lot of pollution. Children should be kept inside when air quality is poor, or should at least be discouraged from intense outdoor activity. Educators and parents should be aware that nearby construction and traffic can increase pollution. Mowing school lawns should never occur during school hours since this can cause an allergy or asthma attack. Insecticides should never be sprayed while children are in care. Outdoor air can include odors, pollutants from vehicles, and fumes from stored trash, chemicals, and plumbing vents.”[38]

Indoor Air Quality

There are so many sources of indoor air pollution in childcare facilities that the air is considered to be two to five times more polluted than outdoor air. Common sources of indoor air pollution include combustion sources such as oil, gas, kerosene, coal, wood, and tobacco products; building materials and furnishings as diverse as deteriorated, asbestos-containing insulation, wet or damp carpet, and cabinetry or furniture made of certain pressed wood products; products for household cleaning and maintenance, personal care, or hobbies; central heating and cooling systems and humidification devices; and outdoor sources such as radon, pesticides, and outdoor air pollution.[39]

Key Takeaways

Environmental Tobacco Smoke & Dangers of E-Cigarettes

Environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), otherwise known as secondhand smoke, is a mixture of the smoke given off by the burning end of a cigarette, or cigar, and the smoke exhaled by smokers. Secondhand smoke contains more than 4,000 substances, several of which are known to cause cancer. Children are particularly vulnerable to the effects of secondhand smoke because they are still developing physically, have higher breathing rates than adults, and have little control over their environment, including where and when the adults in their world choose to smoke. Exposure to secondhand smoke can cause asthma, and places infants and children at increased risk for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), pneumonia, bronchitis, and middle ear infections.[41]What About E-Cigarettes?The aerosol from e-cigarettes is not harmless. It can contain harmful and potentially harmful chemicals, including nicotine; ultrafine particles that can be inhaled deep into the lungs; flavoring such diacetyl, a chemical linked to a serious lung disease; volatile organic compounds such as benzene, which is found in car exhaust; and heavy metals, such as nickel, tin, and lead.

Scientists are still working to understand more fully the health effects and harmful doses of e-cigarette contents when they are heated and turned into an aerosol, both for active users who inhale from a device and for those who are exposed to the aerosol secondhand. Another risk to consider involves defective e-cigarette batteries that have been known to cause fires and explosions, some of which have resulted in serious injuries. Most of the explosions happened when the e-cigarette batteries were being charged.[43]

Mold

Mold is a fungus that thrives indoors when excessive moisture or water accumulates indoors or when moisture problems remain undiscovered or un-addressed. There are molds that can grow on wood, paper, carpet, and foods. There is no practical way to eliminate all mold and mold spores in the indoor environment. The way to control indoor mold growth is to control moisture.

Mold needs to be controlled in childcare settings to avoid possible health impacts for infants and children, including allergic reactions, asthma, and other respiratory issues.[44]

Integrated Pest Management

Exposure to pests such as cockroaches, rodents, ants, and stinging insects in childcare centers may place children at risk for disease, asthma attacks, bites, and stings. Improper use of pesticides can also place children at risk. A recent study of pesticide use in child care centers revealed that 75% of centers reported at least one pesticide application in the last year. Several factors increase both children’s exposures and their vulnerability to these exposures compared to adults. Children spend more time on the floor, where residues can transfer to skin and be absorbed.

Young children also frequently place their hands and objects in their mouths, resulting in the non-dietary ingestion of pesticides. Children are less developed immunologically, physiologically, and neurologically, and therefore may be more susceptible to the adverse effects of chemicals and toxins. There is increasing evidence of adverse effects of pesticides on young children, particularly on neurodevelopment.[45]

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is an effective and environmentally sensitive approach to pest management that relies on a combination of common-sense practices. IPM programs use current, comprehensive information on the life cycles of pests and their interaction with the environment.

Integrated Pest Management “(IPM) is a safer, more effective, longer-lasting method of pest control that emphasizes pest prevention by eliminating pests’ access to food, water, and shelter. When using IPM, properly identify the pest and know why it’s there so an appropriate combination of different pest control methods can be used for better effectiveness in controlling the pest.”[46] This information, in combination with the last toxic available pest control methods, is used to manage pest damage by the most economical means, and with the least possible hazard to people, property, and the environment.[47]

Chemical Hazards

A child born today will grow up exposed to more chemicals than a child from any other generation in our nation’s history. Of the 85,000 synthetic chemicals in commerce today, only a small fraction has been tested for toxicity on human health.

A 2005 study found 287 different chemicals in cord blood of 10 newborn babies – chemicals from pesticides, fast food packaging, coals, gasoline emissions, and trash incineration. Children are more vulnerable to toxic chemicals because their bodies are still growing and developing.[49]

Plastics in Child Care Settings

Certain types of plastics contain chemicals such as phthalates, bisphenol A (BPA), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polystyrene that may be toxic to children. These plastics can be found in baby bottles, sippy cups, teething rings, pacifiers, and toys. When these items are in a child’s mouth or when they are heated (such as in a microwave), children can be exposed to harmful chemicals that have the potential to mimic or suppress hormones and disrupt normal growth and development.[50]

Drinking Water

The United States has one of the safest public drinking water supplies in the world. Over 286 million Americans get their tap water from a community water system. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates drinking water quality in public water systems and sets maximum concentration levels for water chemicals and pollutants.

Sources of drinking water are subject to contamination and require appropriate treatment to remove disease-causing contaminants. Contamination of drinking water supplies can occur in the source water as well as in the distribution system after water treatment has already occurred. There are many sources of water contamination, including naturally occurring chemicals and minerals (for example, arsenic, radon, uranium), local land use practices (fertilizers, pesticides, concentrated feeding operations), manufacturing processes, and sewer overflows or wastewater releases.

The presence of contaminants in water can lead to adverse health effects, including gastrointestinal illness, reproductive problems, and neurological disorders.[51] Young children are at particular risk for exposure to contaminants in drinking water because, pound for pound, they drink more water than adults (including water used to prepare formula), and because their immature body systems are less efficient at detoxification. Exposure to lead in drinking water is a serious health concern, especially for young children and infants since elevated lead levels in children may result in delays in physical or mental development, lower IQ, and even brain damage.[52]

Under the federal regulations of the Safe Drinking Water Act, all water suppliers must notify consumers quickly when there is a serious problem with water quality. Water systems serving the same people year-round must provide annual consumer confidence reports on the source and quality of their tap water. National drinking water standards are legally enforceable, which means that both U.S. EPA and states can take enforcement actions against water systems not meeting safety standards. [54]

Pause to Reflect

| What are five important things that early care and education programs should remember about environmental health to keep children healthy? |

Illness in Early Care and Education Programs

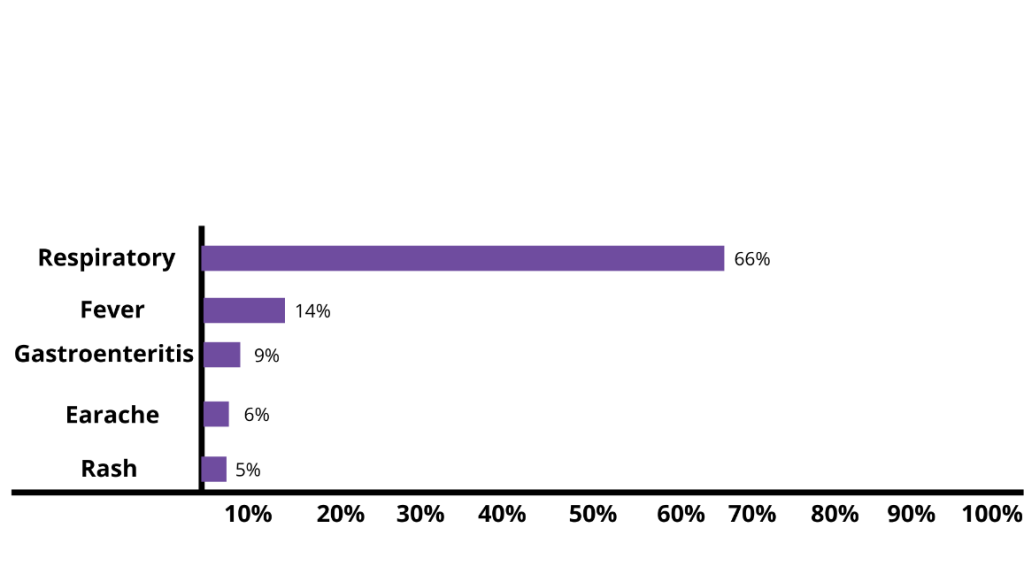

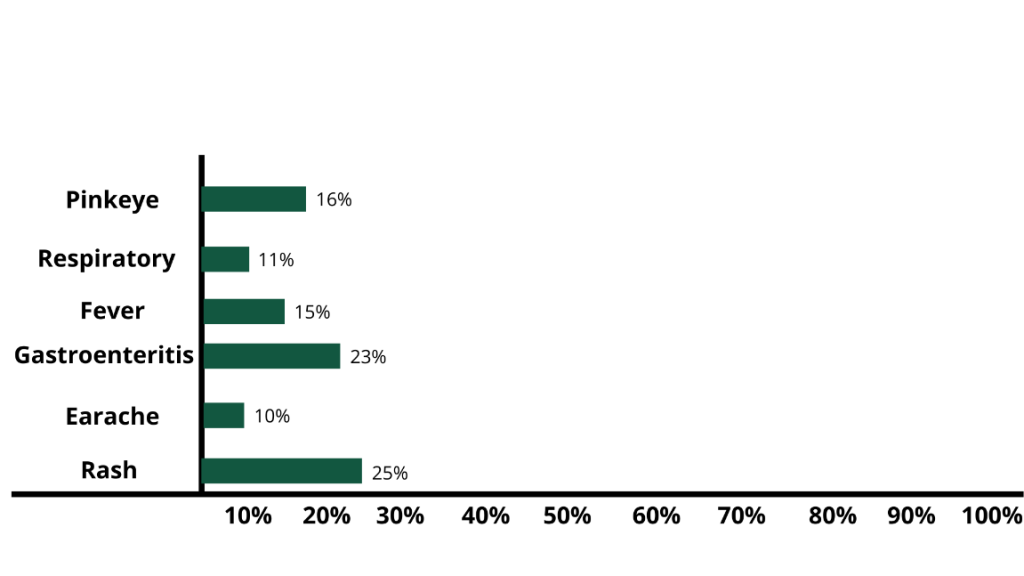

The most frequent infectious disease symptoms that are reported by early care and education settings are sore throat, runny nose, shortness of breath or cough, fever, vomiting and diarrhea (gastroenteritis), earaches, and rashes.

However, these are not the symptoms that necessarily lead to absences. In fact, although respiratory symptoms are most common, it’s rashes and gastrointestinal disease that more often keep children from attending their early education programs. This is more a reflection of exclusion policies than real risk of serious illness.[2]

It’s important for early childhood programs to identify illness accurately and respond in ways that protect all children and staff health (whether it be to allow them to stay in care or to exclude them from care).

Identifying Infectious Disease

When you are familiar with different infectious diseases, it’s easier to identify them in children and know whether or not children (and staff) who are affected should be excluded from the early care and education program.

Common Cold

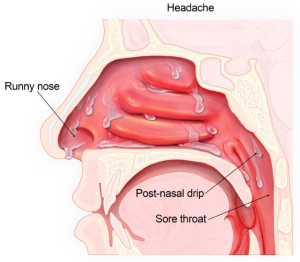

A child is sneezing and has a stuffy, runny nose. It’s quite likely that they have a common cold. As presented in Chapter 8, children get sick many times a year, probably between 4 and 12 times, depending on age and amount of time in child care. Many of these are likely due to the common cold. More than 200 viruses can cause a cold, but rhinoviruses are the most common type.

Symptoms of a cold usually peak within 2 to 3 days and can include:

- Sneezing

- Stuffy nose

- Runny nose

- Sore throat

- Coughing

- Mucus dripping down your throat (post-nasal drip)

- Watery eyes

- Fever (although most people with colds do not have fever)

When viruses that cause colds first infect the nose and air-filled pockets in the face (sinuses), the nose makes clear mucus. This helps wash the viruses from the nose and sinuses. After 2 or 3 days, mucus may change to a white, yellow, or green color. This is normal and does not mean an antibiotic is needed. Some symptoms, particularly runny nose, stuffy nose, and cough, can last for up to 10 to 14 days, but those symptoms should be improving during that time.

There is no cure for a cold. It will get better on its own—without antibiotics. When a child with a cold is feeling well enough to participate and staff are able to provide adequate care for them and all of the other children, the child does not need to be excluded from care.

Because colds can have similar symptoms to flu, it can be difficult to tell the difference between the two illnesses based on symptoms alone. Flu and the common cold are both respiratory illnesses, but they are caused by different viruses.[5]

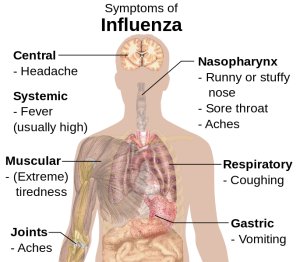

Influenza (Flu)

In general, flu is worse than a cold, and symptoms are more intense. People with colds are more likely to have a runny or stuffy nose. Colds generally do not result in serious health problems, such as pneumonia, bacterial infections, or hospitalizations. Flu can have very serious associated complications.[6]

Flu can cause mild to severe illness, and at times can lead to death. Flu usually comes on suddenly. People who have flu often feel some or all of these symptoms:

- Fever (common, but not always) or feeling feverish/chills

- cough

- sore throat

- runny or stuffy nose

- muscle or body aches

- headaches

- fatigue (tiredness)

- some people may have vomiting and diarrhea, though this is more common in children than adults.

Most people who get flu will recover in a few days to less than two weeks, but some people will develop complications (such as pneumonia) as a result of flu, some of which can be life-threatening and result in death.

Sinus and ear infections are examples of moderate complications from flu, while pneumonia is a serious flu complication that can result from either influenza virus infection alone or from co-infection of flu virus and bacteria. Other possible serious complications triggered by flu can include inflammation of the heart (myocarditis), brain (encephalitis) or muscle (myositis, rhabdomyolysis) tissues, and multi-organ failure (for example, respiratory and kidney failure). Flu virus infection of the respiratory tract can trigger an extreme inflammatory response in the body and can lead to sepsis, the body’s life-threatening response to infection. Flu also can make chronic medical problems worse. For example, people with asthma may experience asthma attacks while they have flu.[8]

A yearly flu vaccine is the first and most important step in protecting against influenza and its potentially serious complications for everyone 6 months and older. While there are many different flu viruses, flu vaccines protect against the 3 or 4 viruses that research suggests will be most common. Flu vaccination can reduce flu illnesses, doctors’ visits, missed school due to flu, prevent flu-related hospitalizations, and reduce the risk of dying from influenza. Also, there are data to suggest that even if someone gets sick after vaccination, their illness may be milder.[9]

Once a person has the flu, their health care provider may recommend antiviral drugs. When used for treatment, antiviral drugs can lessen symptoms and shorten the length of sickness by 1 or 2 days. They also can prevent serious flu complications, like pneumonia. For people at high risk of serious flu complications (including children), treatment with antiviral drugs can mean the difference between milder or more serious illness possibly resulting in a hospital stay. CDC recommends prompt treatment for people who have influenza infection or suspected influenza infection and who are at high risk of serious flu complications.[10]

As with a cold, a child with the flu does not need to be excluded if staff can care for them and all of the other children and they feel well enough to participate.

Avoiding Spreading Germs to Others

Early care and education programs should teach children and model good cough and sneeze etiquette. Always sneeze or cough into a tissue that is discarded after use. If a tissue is not available, use your upper sleeve, completely covering the mouth and nose. Always wash hands after coughing, sneezing, and blowing noses. [11]

Sinusitis (Sinus Infection)

Sinus infections happen when fluid builds up in the air-filled pockets in the face (sinuses), which allows germs to grow. Viruses cause most sinus infections, but bacteria can cause some sinus infections.

Common symptoms of sinus infections include:

- Runny nose

- Stuffy nose

- Facial pain or pressure

- Headache

- Mucus dripping down the throat (post-nasal drip)

- Sore throat

- Cough

- Bad breath

Most sinus infections usually get better on their own without antibiotics.[14] As with colds and flu, a child does not need to be automatically excluded from care for a sinus infection.

Pause to Reflect

| What was your last experience with an upper respiratory infection (such as cold, flu, or sinus infection? If a child had the same symptoms as you, would they have needed to be excluded from care? |

Sore Throat

A sore throat can make it painful to swallow. A sore throat can also feel dry and scratchy. Sore throat can be a symptom of the common cold, allergies, strep throat, or other upper respiratory tract illness. Strep throat is an infection in the throat and tonsils caused by bacteria called group A Streptococcus (also called Streptococcus pyogenes).

Infections from viruses are the most common cause of sore throats. The following symptoms suggest a virus is the cause of the illness instead of the bacteria called group A strep:

- Cough

- Runny nose

- Hoarseness (changes in your voice that makes it sound breathy, raspy, or strained)

- Conjunctivitis (also called pink eye)

The most common symptoms of strep throat include:

- Sore throat that can start very quickly

- Pain when swallowing

- Fever

- Red and swollen tonsils, sometimes with white patches or streaks of pus

- Tiny red spots on the roof of the mouth

- Swollen lymph nodes in the front of the neck

A doctor can determine the likely cause of a sore throat. If a sore throat is caused by a virus, antibiotics will not help. Most sore throats will get better on their own within one week and are not cause for exclusion from child care.

Since bacteria cause strep throat, antibiotics are needed to treat the infection and prevent rheumatic fever and other complications. A doctor cannot tell if someone has strep throat just by looking in the throat. If a doctor suspects strep throat, they may test to confirm diagnosis. A child with strep throat should be excluded from care until they no longer have fever AND have taken antibiotics for at least 24 hours.[15]

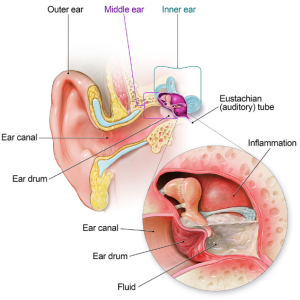

Ear Infection

There are different types of ear infections. Middle ear infection (acute otitis media) is an infection in the middle ear.

Another condition that affects the middle ear is called otitis media with effusion. It occurs when fluid builds up in the middle ear without being infected and without causing fever, ear pain, or pus build-up in the middle ear.

When the outer ear canal is infected, the condition is called swimmer’s ear, which is different from a middle ear infection.

Middle Ear Infection

A middle ear infection may be caused by:

- Bacteria, like Streptococcus pneumoniaeand Haemophilus influenza (nontypeable) – the two most common bacterial causes

- Viruses, like those that cause colds or flu

Common symptoms of middle ear infection in children can include:

- Ear pain

- Fever

- Fussiness or irritability

- Rubbing or tugging at an ear

- Difficulty sleeping

A can make the diagnosis of a middle ear infection by looking inside the child’s ear to examine the eardrum and see if there is pus in the middle ear. Antibiotics are often not needed for middle ear infections because the body’s immune system can fight off the infection on its own. However, sometimes antibiotics, such as amoxicillin, are needed to treat severe cases right away or cases that last longer than 2–3 days.[17]

Swimmer’s Ear

Ear infections can be caused by leaving contaminated water in the ear after swimming. This infection, known as “swimmer’s ear” or otitis externa, is not the same as the common childhood middle ear infection. The infection occurs in the outer ear canal and can cause pain and discomfort for swimmers of all ages.

Symptoms of swimmer’s ear usually appear within a few days of swimming and include:

- Itchiness inside the ear.

- Redness and swelling of the ear.

- Pain when the infected ear is tugged or when pressure is placed on the ear.

- Pus draining from the infected ear.

Although all age groups are affected by swimmer’s ear, it is more common in children and can be extremely painful. If swimmer’s ear is suspected, a healthcare provider should be consulted. Swimmer’s ear can be treated with antibiotic ear drops.[18]

Head Lice

Head lice are parasitic insects that live on the head. They survive by feeding on human blood. Lice infestations are spread most commonly by close person-to-person contact. Lice move by crawling; they cannot hop or fly.

Adult head lice are 2–3 mm in length. Head lice infest the head and neck and attach their eggs to the base of the hair shaft. Lice move by crawling; they cannot hop or fly.[19]

Symptoms of a head lice infestation include:

- Tickling feeling of something moving in the hair.

- Itching, caused by an allergic reaction to the bites of the head louse.

- Irritability and difficulty sleeping; head lice are most active in the dark.

- Sores on the head caused by scratching. These sores can sometimes become infected with bacteria found on the person’s skin.

Head-to-head contact with a person who already has an infestation is the most common way to get head lice. Head-to-head contact is common during play at school, at home, and elsewhere (sports activities, playground, slumber parties, camp).

Although uncommon, head lice can be spread by sharing clothing or belongings. This happens when lice crawl, or the nits that are attached to shed hair hatch, and get on the shared clothing or belongings. Examples include:

- Sharing clothing (hats, scarves, coats, sports uniforms) or articles (hair ribbons, barrettes, combs, brushes, towels, stuffed animals) recently worn or used by a person with an infestation;

- Or lying on a bed, couch, pillow, or carpet that has recently been in contact with a person with an infestation.

Dogs, cats, and other pets do not play a role in the spread of head lice.

The diagnosis of a head lice infestation is best made by finding a live nymph or adult louse on the scalp or hair of a person. Because nymphs and adult lice are very small, move quickly, and avoid light, they can be difficult to find. Use of a magnifying lens and a fine-toothed comb may be helpful to find live lice.

If crawling lice are not seen, finding nits firmly attached within a ¼ inch of base of the hair shafts strongly suggests, but does not confirm, that a person is infested and should be treated. Nits that are attached more than ¼ inch from the base of the hair shaft are almost always dead or already hatched. Nits are often confused with other things found in the hair such as dandruff, hair spray droplets, and dirt particles. If no live nymphs or adult lice are seen, and the only nits found are more than ¼-inch from the scalp, the infestation is probably old and no longer active and does not need to be treated.[21]

Treatment for head lice is recommended for persons diagnosed with an active infestation. All household members and other close contacts should be checked; those persons with evidence of an active infestation should be treated with an over-the-counter or prescription medication (following the provided instructions).

Hats, scarves, pillow cases, bedding, clothing, and towels worn or used by the person with the infestation in the 2-day period just before treatment is started can be machine washed and dried using the hot water and hot air cycles because lice and eggs are killed by exposure for 5 minutes to temperatures greater than 128.3°F. Items that cannot be laundered may be dry-cleaned or sealed in a plastic bag for two weeks. Items such as hats, grooming aids, and towels that come in contact with the hair of a person with an infestation should not be shared. Vacuuming furniture and floors can remove hairs that might have viable nits attached. Head lice do not survive long if they fall off a person and cannot feed.

After treatment, it’s important to check the hair and comb with a nit comb to remove nits and lice every 2–3 days which will decrease the chance of self–reinfestation. Checking for 2–3 weeks will ensure that all lice and nits are gone.[23]

No More “No Nits” Policies

Children diagnosed with live head lice do not need to be sent home early from early care and education programs or school; they can go home at the end of the day, be treated, and return to class after appropriate treatment has begun. Nits may persist after treatment, but successful treatment should kill crawling lice.

Head lice can be a nuisance but they have not been shown to spread disease. Personal hygiene or cleanliness in the home or school has nothing to do with getting head lice.

Both the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the National Association of School Nurses (NASN) advocate that “no-nit” policies should be discontinued. “No-nit” policies that require a child to be free of nits before they can return to schools should be discontinued for the following reasons:

· Many nits are more than ¼ inch from the scalp. Such nits are usually not viable and very unlikely to hatch to become crawling lice, or may in fact be empty shells, also known as ‘casings’.

· Nits are cemented to hair shafts and are very unlikely to be transferred successfully to other people.

· The burden of unnecessary absenteeism to the students, families and communities far outweighs the risks associated with head lice.

· Misdiagnosis of nits is very common during nit checks conducted by nonmedical personnel.[24]

NOTE: This textbook was written for California rules. Minnesota’s Rule 3 Licensing Rule still requires exclusion for children with lice.

Pause to Reflect

| What experience with or knowledge do you have about policies that specific early education and care program and schools have on head lice? Are (or were) those policies “no nits” or in line with the recommendations above? |

Other Illnesses

To learn more about the following illnesses, go to Appendix J.

- Bronchitis

- Chickenpox

- Conjuctivitis (Pink Eye)

- Fifth Disease (Slapped Cheek)

- Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease

- Hepatitis A

- Impetigo

- Measles

- Meningitis

- Molluscum Contagiosum

- Mumps

- Norovirus

- Pertussis

- Pinworms

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus

- Ringworm

- Roseola

- Rotavirus

- Rubella (German Measles)

- Shigella

- Tuberculosis

Danger of Infectious Disease for Adults

| Because early care and education program employees are around children who are at higher risk of infectious diseases and have limited understanding of hygiene practices, those employees are also at greater risk for getting sick.

While most illness that are spread in early care and education programs are not serious, some can be very dangerous. Knowledge about illness and how to prevent its spread helps. Being fully immunized (from childhood illness and or vaccines) protects adult health as well. Employees that are or could become pregnant want to be especially careful because first time exposure to chickenpox, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Fifths disease, and Rubella can cause major damage to fetal health, birth defects, and even fetal death. [25] |

Reportable Diseases

Some diseases are enough of a threat to the community that it is required that diagnosed cases are reported to the local health department. See Table 9.1 for which diseases must be reported, how, and how quickly.

Table 5.3 – Diseases Reportable to Local Health Department (required by Licensing in Minnesota) [26]

Amebiasis (Entamoeba histolytica/dispar)

Anaplasmosis

Anthrax

Arboviral disease

Babesiosis

Blastomycosis

Botulism

Brucellosis

Campylobacteriosis

Cat scratch disease

Chancroid

Chlamydia

Cholera

Coccidioidomycosis

Cryptosporidiosis

Cyclosporiasis

Dengue virus infection

Diphtheria

Diphyllobothrium latum

Ehrlichiosis

Encephalitis (caused by viral agents)

Enterobacter sakazakii

Enteric E. coli infection

Giardiasis

Gonorrhea

Haemophilus influenzae disease (all invasive

disease)

Hantavirus infection

Hemolytic uremic syndrome

Hepatitis (all viral types)

Histoplasmosis

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

infection, including Acquired

Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

Influenza (unusual case incidence, critical

illness, or laboratory confirmed cases)

Kawasaki disease

Kingella spp.

Legionellosis

Leprosy (Hansen’s disease)

Leptospirosis

Listeriosis

Lyme disease

Malaria

Measles

Meningitis (caused by viral agents)

Meningococcal disease (Neisseria

meningitidis)

Mumps

Neonatal Sepsis

Orthopox virus

Pertussis

Plague

Poliomyelitis

Psittacosis

Q fever

Rabies

Retrovirus infections (other than HIV)

Reye syndrome

Rheumatic fever

Rocky Mountain spotted fever

Rubella and congenital rubella syndrome

Salmonellosis (including typhoid)

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

Shigellosis

Smallpox

Staphylococcus aureus (special situations

involving vancomycin resistance or death

DISEASE REPORTING

or critical illness in an otherwise healthy

individual)

Streptococcal disease (invasive disease)

Syphilis

Tetanus

Toxic shock syndrome

Toxoplasmosis

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy

Trichinosis

Tuberculosis

Tularemia

Typhus

Unexplained deaths and unexplained

critical illness (possibly due to an

infectious cause)

Varicella-zoster disease (primary (chickenpox)

and recurrent (shingles))

Vibrio spp.

Yellow fever

Yersiniosis

Unusual or increased case incidence of any suspect infectious illness is also reportable.

Exclusion Policies

Most children with mild illnesses can safely attend child care. “Many health policies concerning the care of ill children [including exclusion policies] have been based upon common misunderstandings about contagion, risks to ill children, and risks to other children and staff. Current research clearly shows that certain ill children do not pose a health threat. Also, the research shows that keeping certain other mildly ill children at home or isolated at the child care setting will not prevent other children from becoming ill.” [27]

But there are times when exclusion is the right answer. Licensing states that a child may be too sick to attend if:

- The child does not feel well enough to participate comfortably in the program’s activities.

- The staff cannot adequately care for the sick child without compromising the care of the other children.

- The child has any of the following symptoms unless a health provider determines that the child is well enough to attend and that the illness is not contagious:

- Fever (above 100° F. axillary or above 101° F. orally) accompanied by behavior change and other signs or symptoms of illness (i.e., the child looks and acts sick)

- Signs or symptoms of possibly severe illness (e.g., persistent crying, extreme irritability, uncontrolled coughing, difficulty breathing, wheezing, lethargy)

- Diarrhea: Changes from the child’s usual stool pattern–increased frequency of stools, looser/watery stools, stool runs out of the diaper, or child can’t get to the bathroom in time.

- Vomiting more than once in the previous 24 hours

- Mouth sores with drooling

- Rash with a fever or behavior change

The child has any of the following diagnoses from a health provider (until treated and/or no longer contagious):

- Infectious conjunctivitis/pink-eye (with eye discharge)-until 24 hours after treatment started

- Scabies, head lice, or other infestation-until 24 hours after treatment and free of nits

- Impetigo-until 24 hours after treatment started

- Strep throat, scarlet fever, or other strep infection-until 24 hours after treatment started and the child is free of fever

- Pertussis-until five days after treatment started

- Tuberculosis (TB)-until a health care provider determines that the disease is not contagious

- Chicken pox-until six days after start of rash or all sores have crusted over

- Mumps-until nine days after start of symptoms (swelling of “cheeks”)

- Hepatitis A-until seven days after start of symptoms (e.g., jaundice)

- Measles-until six days after start of rash

- Rubella (German measles)-until six days after start of rash

- Oral herpes (if child is drooling or lesions cannot be covered)-until lesions heal

- Shingles (if lesions cannot be covered)-until lesions are dry[28]

If there is an outbreak of any reportable illness (See Table 9.X), a child or staff member who meets the following criteria as determined by the local health department or a health care provider to be:

- contributing to transmission of the illness

- not adequately immunized when the disease is vaccine-preventable

- at increased risk due to the pathogens being circulated.

They can be readmitted when the health department official or that health care provider decides that the risk of transmission is no longer present.[29]

What to do When a Child Requires Exclusion

When a child becomes ill enough to be excluded, they should be immediately isolated from other children. Early care and education programs are required to be equipped to isolate and care for any child who becomes ill during the day. The isolation area shall be located to afford easy supervision of children by center staff and equipped with a mat, cot, couch or bed for each ill child (or a crib if caring for infants).

The child’s authorized representative shall be notified immediately when the child becomes ill enough to require isolation, and shall be asked to have the child picked up from the center as soon as possible.[30]

See Table 9.2 for a list of illnesses that require exclusion and when children who are diagnosed with those illnesses can return to care.

Table 5.4 – Conditions that Require Exclusion [31]

9503.0080 EXCLUSION OF SICK CHILDREN. A child with any of the following conditions or behaviors is a sick child and must be excluded from a center not licensed to operate a sick care program. If the child becomes sick while at the center, the child must be isolated from other children in care and the parent called immediately. A sick child must be supervised at all times. The license holder must exclude a child:

A. with a reportable illness or condition as specified in part 4605.7040 that the commissioner of health determines to be contagious and a physician determines has not had sufficient treatment to reduce the health risk to others;

B. with chicken pox until the child is no longer infectious or until the lesions are crusted over;

C. who has vomited two or more times since admission that day;

D. who has had three or more abnormally loose stools since admission that day;

E. who has contagious conjunctivitis or pus draining from the eye;

F. who has a bacterial infection such as streptococcal pharyngitis or impetigo and has not completed 24 hours of antimicrobial therapy;

G. who has unexplained lethargy;

H. who has lice, ringworm, or scabies that is untreated and contagious to others;

I. who has a 100 degree Fahrenheit axillary or higher temperature of undiagnosed origin before fever reducing medication is given;

J. who has an undiagnosed rash or a rash attributable to a contagious illness or condition;

K. who has significant respiratory distress;

L. who is not able to participate in child care program activities with reasonable comfort; or

M. who requires more care than the program staff can provide without compromising the health and safety of other children in care.

Statutory Authority:

History: 13 SR 173

Published Electronically: October 8, 2007

Pause to Reflect

| Consider the following situations. Should each child be excluded from care or not? If so, why and when should the child return? If not, what should the teacher/caregiver do?

1. Mario’s dad drops him off and let’s Ms. Michelle know that he is a little under the weather. He is not running a fever, but has a mild cough and a runny nose. But he ate a good breakfast and has a pretty typical level of energy. 2. About an hour into the day, Li vomits. Mr. Abraham checks and she has a fever of 101.3°. She looks a little pale and just wants to lay down. As he goes to call Li’s family, she vomits again. 3. When Latanya goes to change Daniel’s diaper she notices a rash on his stomach. She checks his temperature and he is not running a fever. He is not scratching at it or seemingly in any discomfort. She remembers that he has a history of eczema and contact dermatitis. 4. Apurva wakes up from naptime with discharge coming from a slightly swollen and bloodshot right eye. She tells Ms. Maria that her eye hurts and is “kind of itchy.” Now, come up with your own examples of a child that should be excluded from care and that should not automatically be excluded. |

Caring for Mildly Ill Children

Because young in early care and education programs have high incidence of illness and may have conditions (such as eczema and asthmas), providers should be prepared to care for mildly ill children, at least temporarily. And since we know that excluding most mildly ill children doesn’t prevent the spread of illness and can have negative effects on families, programs should consider whether they can care for children with mild symptoms (not meeting the exclusion policy). The California Childcare Health Program poses the following questions to consider:

- Are there sufficient staff (including volunteers) to provide minor modifications that a child might need (such as quiet activities or extra fluids)?

- Are staff willing and able to care for the child’s symptoms (such as wiping a runny nose and checking a fever) without neglecting the care of other children in the group?

- Is there a space where the mildly ill child can rest if needed?

- Are families able or willing to pay extra for sick care if other resources are not available, so that you can hire extra staff as needed?

- Have families made alternative arrangements for someone to pick up and care for their ill children if they cannot?”

It’s important that programs recognize the families have to weigh many things when trying to decide whether or not to send a child to child care. They must consider how the child feels (physically and emotionally), whether or not the program can provide care for the specific needs of the child, what alternative care arrangements are available, as well as the income they may lose if they have to stay home.[32]

Responding to Illness that Requires Medical Care

“Some conditions, require immediate medical help. If the parents can be reached, tell them to come right away and to notify their medical provider.

Call Emergency Medical services (9-1-1) immediately and also notify parents if any of the following things happen:

· You believe a child needs immediate medical assessment and treatment that cannot wait for parents to take the child for care.

· A child has a stiff neck (that limits his ability to put his chin to his chest) or severe headache and fever.

· A child has a seizure for the first time.

· A child who has a fever as well as difficulty breathing.

· A child looks or acts very ill, or seems to be getting worse quickly.

· [A child has s]kin or lips that look blue, purple or gray.

· A child is having difficulty breathing or breathes so fast or hard that he or she cannot play, talk, cry or drink.

· A child who is vomiting blood.

· A child complains of a headache or feeling nauseous, or is less alert or more confused, after a hard blow to the head.

· Multiple children have injuries or serious illness at the same time.

· A child has a large volume of blood in the stools.

· A child has a suddenly spreading blood-red or purple rash.

· A child acts unusually confused.

· [A child is u]nresponsive or [has] decreasing responsiveness.

Tell the parent to come right away, and get medical help immediately, when any of the following things happen. If the parent or the child’s medical provider is not immediately available, call 9-1-1 (EMS) for immediate help:

· A fever in any child who appears more than mildly ill.

· An infant under 2 months of age has an axillary (“armpit”) temperature above 100.4º F.

· An infant under four months of age has two or more forceful vomiting episodes (not the simple return of swallowed milk or spit-up) after eating.

· A child has neck pain when the head is moved or touched.

· A child has a severe stomach ache that causes the child to double up and scream.

· A child has a stomach ache without vomiting or diarrhea after a recent injury, blow to the abdomen or hard fall.

· A child has stools that are black or have blood mixed through them.

· A child has not urinated in more than eight hours, and the mouth and tongue look dry.

· A child has continuous, clear drainage from the nose after a hard blow to the head.

· A child has a medical condition outlined in his special care plan as requiring medical attention.

· [A child has a]n injury that may require medical treatment such as a cut that does not hold together after it is cleaned.”[33]

Administering Medications

Some children in your early care and education setting may need to take medications during the hours you provide care for them. It’s important that early care and education programs have a written policy for the use of prescription and nonprescription medication.[34]

According to licensing, programs that choose to handle medications must abide by the following:

- All prescription and nonprescription medications shall be centrally stored in a safe place inaccessible to children, with an unaltered label, and labeled with the child’s name and date

- A refrigerator shall be used to store any medication that requires refrigeration.

- Prescription medications may be administered with written permission by the child’s authorized representatives in accordance with the label instructions by the physician

- Nonprescription medications may be administered without approval or instructions from the child’s physician with written approval and instructions from the child’s authorized representative and when administered in accordance with the product label directions.

Valid reasons for an early care and education program to consider administering medication.

- Some medication dosing cannot be adjusted to be taken before and after care (and keeping them out of care when otherwise well enough to attend, would be a hardship for families.

- Some children may have chronic conditions that may require urgent administration of medication (such as asthma and diabetes).[36]

Communication with Families

When children are excluded from care, it’s important to provide documentation for families of how the child meets the guidelines in your exclusion policy and what needs to happen before the child can return to care. See Appendix K for a possible form that programs could use.

Programs are also required to inform families when children are exposed to a communicable disease. See Appendix L for an example of a notice of exposure form you can provide to families so they know what signs of illness to watch for and to seek medical advice when necessary.[37]

Pause to Reflect

|

Why is it important for early care and education programs to communicate clearly with families regarding communicable illness? |

Summary

Understanding how illness is spread, helps early care and education programs prevent the spread of illness. Immunizations also play an important role in preventing illness. And when program staff use universal precautions, including handwashing, cleaning and disinfecting, and proper disposal of waste, they also prevent the spread of illness.

Programs must also be aware of environmental hazards that present a threat to children’s health. These include both indoor and outdoor air quality, mold, and chemicals. Programs should use integrated pest management and make sure that their drinking water is safe as well.

Becoming familiar with infectious diseases that are common in early childhood enables early care and education program staff to identify illness and respond appropriately. This included knowing when children (and staff) should be excluded from care and what needs to happen before they should come back.

Programs must create policies on how they will handle children that are mildly ill (those that need care before they can be picked up from care and those that do not require exclusion) and children who have illness that requires medical care. Programs who choose to administer medication, must be familiar with the licensing regulations they must follow.

Open communication with families is important when a child becomes ill or is potentially exposed to an illness. Helping families understand and follow policies regarding exclusion is vital to keeping everyone in the program as healthy as possible.

Chapter 5 Review

Resources for Further Exploration

· Health and Safety in the Child Care Setting: Prevention of Infectious Disease A Curriculum for the Training of Child Care Providers: https://cchp.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra181/f/idc2book.pdf

· A Quick Guide to Common Childhood Diseases (Canadian resource): bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Guidelines%20and%20Forms/Guidelines%20and%20Manuals/Epid/Other/Epid_GF_childhood_quickguide_may_09.pdf

· Common Childhood Infections – A Guide for Principals, Teachers and Child Care Providers (Canadian resource): https://www.tbdhu.com/sites/default/files/files/resource/2017-03/Common%20Childhood%20Infections%20Manual_0.pdf

· Georgia School Resource Health Manual: https://www.choa.org/~/media/files/Childrens/medical-professionals/nursing-resources/ch-4-communicable-diseases-and-infection-control.pdf?la=en

· Diseases & Conditions A-Z Index: https://www.cdc.gov/diseasesconditions/az/a.html

· Childhood Infectious Illnesses: http://www.ocwtp.net/PDFs/Trainee%20Resources/Preservice/Session10DiseaseChartOption.pdf

· Appropriate Antibiotic Use: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/community/index.html

· When to Keep Your Child Home from Child Care: https://www.healthychildren.org/English/family-life/work-play/Pages/When-to-Keep-Your-Child-Home-from-Child-Care.aspx

References

[1] Image by College of the Canyons ZTC Team is based on image from Managing Infectious Disease in Head Start Webinar by Head Start Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center, which is in the public domain

[2] Infectious Diseases: Prevention and Management by Head Start Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center is in the public domain