1 Chapter 1: Introduction to Public Speaking

Tammera Stokes Rice, College of the Canyons

Adapted by Katharine O’Connor, Ph.D., Florida SouthWestern State College

|

LEARNING OBJECTIVES |

|

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

|

Figure 1.1: Official Portrait of President Barack Obama1

Introduction

Have you ever asked a parent for money and not received a response? Have you ever asked your boss if you can leave early from work and they just stare at you for what seemed forever? You may have asked yourself, “Why aren’t they communicating with me?” Well, they are communicating. You see, every verbal and nonverbal response is a form of communication, including silence. Doctor of Psychology and author, Paul Watzlawick (1967), points out in Pragmatics of Human Communication: A Study of Interactional Patterns, Pathologies and Paradoxes one of the five axioms of communication is “One cannot not communicate” (p. 48). As long as there is someone to receive the communication, we are communicating.

In basic terms, communication is the sending and receiving of messages. Does this seem too simple? If so, it’s because IT IS! Of course, there is much more to the story, which is why we have an entire book and class about communication. Yet, this simple definition helps us see that we can learn the basic process of sending and receiving messages when we communicate. Throughout this text, we will learn all about the communication process in order to write and deliver a stellar speech. Let’s start with the models of communication.

Models of Communication

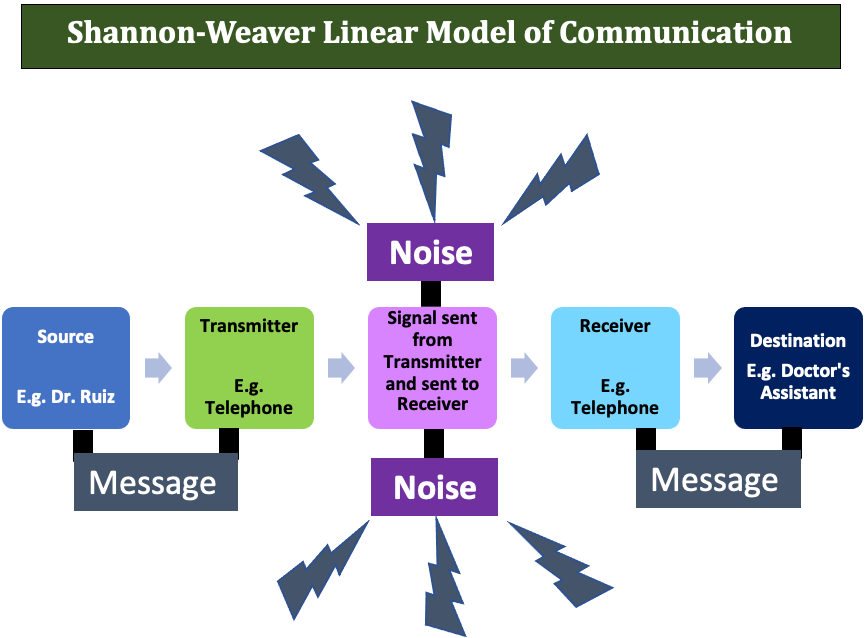

In order to understand the process of communication, we would like to take you back to the earliest model of communication and then provide you with a more contemporary and effective model of communication. Shannon and Weaver’s (1949) model of communication is the linear model. However, today we understand communication as a transactional model of communication. Let’s jump in.

Shannon-Weaver Model of Communication (Linear Model)

An early model of communication widely understood in the field of communication studies is the Shannon-Weaver Model. The model was first developed to improve communication in technologies. Later, social scientists adopted it to understand the communication patterns between individuals. Nowadays, we use it most when we text, email, chat, blog, etc. This is a one-directional model of communication which only moves from sender to receiver without immediate feedback. However, when we give a speech to a live audience, we use a different model which we will highlight below.

Figure 1.2: Shannon-Weaver Model2

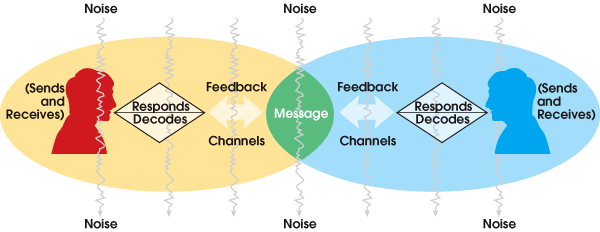

Transactional Model of Communication

So, what happens when we communicate face-to-face? It is no longer one-way communication since we are sending and receiving messages simultaneously. This is called a transactional model of communication since there is a simultaneous exchange of messages from both the sender and receiver. When the sender sends a message to the receiver, the receiver receives the message as it is happening and is also sending messages back to the sender usually in the form of nonverbal communication. That was pretty simple, right? Not. Stay with us, we will get there. Nonverbal communication can include appearance, eye behavior, kinesics (body movement), proxemics (use of gestures), touch (haptics), chronemics, and olfactics. Let’s make sense of all of this.

Figure 1.3: The Transactional Model of Communication3

There are many models Communication theorists use to understand the process; however, in this course, it is important to understand the transactional model of communication using the elements within the public speaking process. In a transactional process, two or more individuals exchange information through the assignment of meaning. What does this mean? The individuals use the elements below to give meaning to what is being said. Here are the elements:

Elements of the Transactional Model

- Sender – the sender is the originator of the message. In public speaking, this is the speaker.

- Receiver – anyone who hears or sees your message. In public speaking, this is your audience.

- Encode – converting ideas, thoughts, and feelings into words or actions.

- Decode – where the receiver interprets words or actions into meaning. Misunderstandings can occur due to issues with denotation or connotation.

- Denotation is the literal or dictionary definition of a word. For example, the dictionary has many definitions of the word “run.” You can put on jogging attire and run a 5K, or you can run to the store for a carton of milk. Can you think of another use of the word run?

- Connotation is the personal, social, cultural, or emotional association the receiver has with the message. For example, you are on the freeway and a police officer turns on their lights behind you. One person sees the lights, immediately looks at their speedometer, and is bummed that they are about to get a ticket for speeding. Someone else sees the lights and may immediately move aside because they know they were going the speed limit, and the police officer must need to get around them. The experience for each person differs based on the connotative meaning of the situation.

- Message – the main idea(s) the sender conveys to the listener.

- Channel – the medium through which the message is sent from the sender to the receiver. This can be both auditory and/or visual. Through the auditory channel, you receive spoken words, while the visual channel receives nonverbals (eye contact, body movements, facial expressions, physical appearance, space, etc.)

- Noise – anything that interferes with the message being encoded or decoded. Noise can be external or internal. There are four types.

- Physical noise is interference from external sounds. For example, people talking, papers rustling, and doors opening and shutting.

- Physiological noise is interference from the internal physical state. For example, hunger, illness, or pain.

- Psychological noise is interference from wandering thoughts. For example, your homework is due tomorrow and you haven’t started, you are worried about getting to work later, you are worried about childcare, or you are thinking about your long to-do list.

- Semantic noise is interference from misunderstood meanings. For example, one might misunderstand the “L sign” with the thumb and index finger which means “Loser” in the U.S., but in China, it means the number eight. Another example is raising your hand in a U.S. classroom means you have a question, but on the streets of New York City it is the action done to call for a cab.

- Context – the situation that influences the speaker, audience, and message.

- Frame of Reference – the lens through which you view the world that informs how we encode and decode messages.

Communication and Public Speaking

In public speaking, a speaker presents a specific message to a relatively large audience in a unique context. As we saw in the transactional model above, each element in public speaking depends on the other. We will outline each element of public speaking below and explain how it ties to communication. Understanding and knowing how to speak effectively in public speaking contexts is critical. Public speaking helps with a variety of academic and career skills, and also helps reduce our fear of communication while building self-confidence.

Figure 1.4: FSW President Jeff Albritten 4

Essential Elements of Public Speaking

There are five essential elements of public speaking. Understanding each of these will provide students with a basic understanding of public communication. Each of the elements must be considered as you craft your speech.

- Speaker – the person who sends a message to the audience.

- Audience – listeners who are actively involved in receiving the message from the speaker.

- Context – the situation that influences the speaker, audience, and message. There are three types:

- Socio-psychological context – the relationship between the speaker and the audience.

- Temporal context – time of day and where the speech fits into the sequence of events.

- Cultural context – the collection of beliefs, attitudes, values, and ways of behaving shared by a group of people.

- Delivery – the methods used to send the message to the audience. There are four methods to deliver a speech:

- Impromptu – There is little to no preparation for this method. Some examples include a spur-of-the-moment toast at an event or the first day of class introductions.

- Memory – This method is when you memorize a speech and then deliver it exactly as rehearsed. Examples of this method include a student on the speech and debate team or actors that memorize their lines.

- Manuscript – This method is a word-for-word iteration of a written message. Examples of this include sportscasters and politicians who read from a teleprompter.

- Extemporaneous – This method is when presentations are researched, prepared for, and rehearsed. It is a planned, conversational, and natural style. This is the typical method used in college classrooms, yet also popular for political addresses and classroom lectures.

- Ethics – both the speaker and the audience have an ethical obligation to one another. The speaker needs to be credible and truthful, use sources, and verify all sources used within the speech. Further, the audience members need to be respectful and good listeners.

Ten Steps for Preparing a Speech

Now that we have discussed the foundational elements, it is time to turn toward the steps for speech success. Next, you will find a list of ten steps that are designed to provide an overview of the main functions of speechmaking, all of which will be applied in this class. When you follow these ten steps, you are likely to succeed. We will go into further detail about each step in the upcoming chapters. This is a preview:

- Determine your audience and why you are speaking.

- Select your topic and identify your general and specific purpose.

- Develop your thesis (central idea).

- Research your topic and gather supporting materials.

- Begin your preparation outline by building and supporting your main points using an organizational pattern.

- Consider your use of language in relation to your audience, ethics, topic, and occasion.

- Construct your introduction, conclusion, and transitions.

- Finalize and review your final preparation outline.

- Create your speaking outline and presentation aids.

- Practice your speech delivery.

Conclusion

This first chapter explained how communication is the sending and receiving of messages as a transactional process. Public Speaking consists of major elements and each element depends on the other making it a transactional process of communication. This book is organized to assist students in creating excellent speeches. In the upcoming chapters, we will cover each of the public speaking steps and the different types of public speeches. By the end of this text, you will be ready to prepare your first speech.

Reflection Questions

- What did you learn about the communication process that you think will help you in this class and in your future career?

- Can you think of someone who you have seen do a speech that had particularly effective or ineffective communication skills? What aspects of the communication process do you think this speaker did or did not use?

- How have differences in connotation led to any misunderstandings you may have had with someone? How can you look at feedback as a possible way to avoid any misunderstanding in the future?

- Are there any aspects of noise have you found to be problematic within your own communication?

Key Terms

Audience

Channel

Communication

Connotation

Context

Cultural Context

Decode

Delivery

Denotation

Encode

Ethics

Extemporaneous

Frame of Reference

Impromptu

Linear Model

Manuscript

Memory

Message

Noise

Physical Noise

Physiological Noise

Psychological Noise

Public speaking

Receiver

Semantic Noise

Sender

Socio-psychological Context

Speaker

Temporal Context

Transactional Model

References

Shannon, C. E., & Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana, IL: The University of Illinois Press, 1-117.

Watzlawick, P., Beavin-Bavelas, & J., Jackson, D. (1967). Pragmatics of human communication: A study of interactional patterns, pathologies, and paradoxes. (pp.48-71). W. W. Norton, New York.