7 Chapter 7: Gathering Materials and Supporting Your Ideas

Amy Fara Edwards and Marcia Fulkerson, Oxnard College

Victoria Leonard, Lauren Rome and Tammera Stokes Rice, College of the Canyons

Adapted by William Kelvin, Professor of Communication Studies, Florida SouthWestern State College

|

LEARNING OBJECTIVES |

|

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

|

Figure 7.1: NYC Public Library 1

Introduction

When was the last time you spent hours on social media looking up people you used to know? Maybe we are looking to see how former schoolmates are doing or we try to identify the underlying meaning of an ex-partner’s posts. As we search for “spilled tea,” we tend to have more questions and need more information, so we continue to click deeper into profiles. Whether we care to admit this or not, we have spent countless hours on this type of “research.” However, this process of asking questions, gathering information, analyzing the truth of that information, then asking more questions and gathering more information is research.

There are similar steps we take in college when researching for a speech or essay, but instead, we search library databases, not social media apps. We pull up article after article and question the truth of new information at each turn, which then leads to more questions and more articles.

Figure 7.2: Study Group 2

The Research Process

Formal research occurs in a step-by-step process to gather content that we then fit into class assignments. In this chapter, we discuss methods of formalizing our research process so it becomes an effective tool for academic research. Let’s start with library databases.

Library Databases

The search for information about our topics can be fun when you start the speechmaking process. Using your library databases will generate higher-quality academic work. Don’t be afraid of the library databases! They work similarly to a Google search, but they produce more peer-reviewed, academic material. Let us explain.

In the beginning, it is okay to use the internet to search for topics, but once you identify a topic, you must use the library database to find the research. The results of a database search will all be peer-reviewed articles, primary sources, books, and other vetted or pre-screened materials; library databases act as a “background check” for your research. One of the key benefits of using library databases is free access to scholarly and full-text articles to be used as the foundation for our work. Libraries purchase subscriptions to these databases that a general internet search cannot access. When selecting research from the library databases you are using material that has been vetted or screened for credibility and reliability. The alternative, traditional search engines, produce countless results flawed by bias and non-scientific approaches.

Exploring Sources

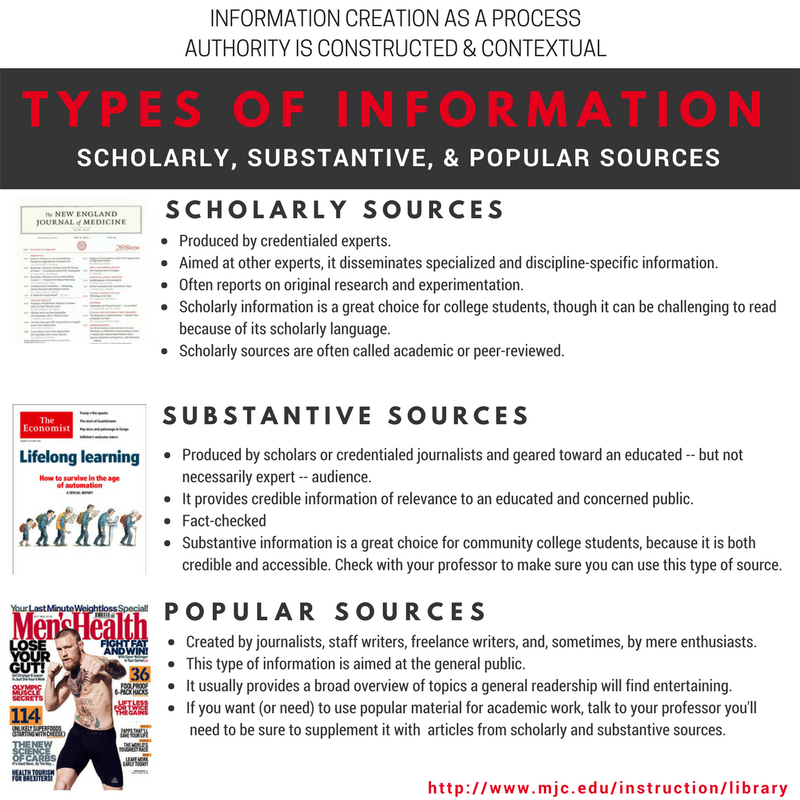

When we are looking for sources for our speech outline, we may be looking for peer-reviewed journals, books, newspapers, or magazines. A peer-reviewed source means that multiple expert reviewers have verified the content. You can feel confident that a peer-reviewed source is trustworthy. Your professor may guide you to the type of sources that are appropriate for your assignment. In academic research, we typically use a blend of sources to gain a balanced view of our topic. One way of looking at types of sources is to compare scholarly sources, substantive sources, and popular sources as the chart below illustrates (Modesto Junior College Library, 2021).

Figure 7.3: Types of Information Chart3

Types of Sources

Scholarly sources are written by credentialed experts for an audience of their peers. They have been vetted, or pre-screened, and selected by a committee of experts. For this reason, they are called peer-reviewed. They are also known as journal articles, scholarly articles, or academic journals. These journal publications may only publish five articles a month as they disseminate specialized, discipline-specific information. You may have heard that many higher education instructors work diligently to produce these kinds of works. They are not easy! Imagine your professors working for a year or longer on a 30-page essay to submit to other professors. The standards are very demanding, but that is what makes the final products so useful.

Substantive sources, on the other hand, are produced by scholars or credentialed journalists for an educated audience, but not an expert audience. Typically, one editor of the publication will vet or pre-screen articles. These publications may include newspapers or magazines. The reason for using the specific source is key. A magazine that is produced monthly has fewer articles that provide more detail. Whereas newspapers are produced daily, which give us quick statistics. For example, The Los Angeles Times might cover the COVID-19 pandemic in a “daily numbers” kind of way, while Newsweek Magazine will provide the detailed context and personalized stories as evidence which makes it more substantial.

Know that these kinds of publications frequently report on scholarly sources. If you’re incorporating a periodical’s interpretation of a scholarly source, consider locating the original source and reading, or at least skimming, it yourself. You may find that the journalists misrepresented or misunderstood certain aspects, or may uncover useful details not included in their secondary account. Secondary sources summarize and relay the work of primary sources, which are often scholarly articles.

Popular sources are written by journalists, staff writers, freelance writers, or sometimes hobbyists for the general public. Although they may be good sources for finding the next recipe or where to find the best beaches or the easiest teacher, they may not have been vetted properly. Largely, they are based on opinion. For academic work, we avoid such sources because they are too broad and offer limited credible information. Let’s talk about the elephant in the room: Wikipedia. Wikipedia may be a good starting point to begin thinking about your research, but it is not up to academic standards. You may find primary resources cited at the very bottom of the Wikipedia page…but have you taken the time to scroll all the way down there? Many instructors will not allow Wikipedia for any portion of your assignment since it is an alterable website.

However, many scholars do begin with Wikipedia as a jumping-off point to gather a basic overview of a subject. Using a crowd-sourced tool like Wikipedia or ChatGPT to learn the “lay of the land” on a subject is perfectly acceptable. But, make sure you continue searching to locate the credible sources that are ultimately the backbone of those crowd-sourced, secondary source entries. For example, Wikipedia may cite a college textbook. That textbook is a secondary source, making Wikipedia a tertiary source in this instance. Have you played the children’s game Telephone? You don’t want two degrees of separation between your work and the sources it is based on.

Types of Evidence

We just described different types of sources. Now, what do we use these sources for? Well, we pull out evidence which becomes the content for our main points.

Examples

Examples are types of evidence that reinforce, clarify, or personalize your ideas. Throughout the reading of this book, and many others, you have experienced the use of examples. Authors say “for example” or “such as” to illustrate their points. For example, if your speech is about the top five brands of sneakers in the United States, you would give examples of different brands, such as Nike and Adidas.

There are different types of examples:

- Brief examples are quick to illustrate a point (showcased in the paragraph directly above).

- Hypothetical examples describe an imaginary or fictitious situation using words like “imagine” or “visualize.” Imagine a world with no Internet. Can you do it? This might be used in a speech about the history of the world wide web.

- Specific instance is a more developed, real example where you illustrate a specific time. For example, you might be informing about the dangers of alcoholism and provide a specific instance of when one of your friends was pulled over for a DWI (don’t drive intoxicated!). You would provide a few sentences about your friend’s situation. A specific instance can sometimes be considered a very short story. A longer story used as evidence is called a narrative.

Narratives

Humans tell a lot of stories. We run to a friend to share good news or we communicate with a sibling when something happens at work. For speeches, we call these more detailed stories that relate to your topic narratives. You can use them in all types of speeches. Ultimately, a narrative is a spoken or written account of connected events. A narrative is a story, and audiences love stories, especially in speeches. Narratives can accomplish several things. They can:

- Explain the way things are. The story would explain the situation by giving the details related to the who, what, where, when, and how it relates to your speech topic. You might tell a story about a friend’s experience having shingles.

- Provide examples of excellent work to follow or admire. This type of story gives reasons for admiration. You might tell a story about a company that offers employees great workspace and health benefits.

- Strengthen or change beliefs and attitudes. This type of story can grab the audience’s attention because they tend to be emotional and highly effective. You might tell a story about a couple who met online and have been married for 15 years; this could be a story to persuade an audience to download their dating app.

Testimony

Testimony is a specific account of someone’s experience, knowledge, or expertise. This type of evidence can be impactful because it comes directly from a person. We use testimony to support our claims. For example, witnesses in a court trial give testimony to share their personal accounts of the events. There are two types of testimony:

- Expert testimony comes from a person who is considered an expert in their field. For example, if our informative speech is on different types of cancer, expert testimony would come from an oncologist. You may obtain such testimony from live interviews or publications. Who else may you consider an expert on types of cancer? Does someone with cancer constitute an expert?

- Lay testimony (sometimes called peer testimony) is information from someone who has experience with the topic but is not a trained expert. So, thinking about the same informative speech example on types of cancer, lay testimony could come from a relative of someone with cancer. They would understand the struggle of watching someone experience cancer and would have secondhand information from the doctor. Lay testimony can provide a simplified and personalized account of the topic.

When using testimony, remember you must explicitly state the name of the person (when possible) and why their testimony matters. Next time you see a clip of courtroom drama, you should be able to identify both the expert and the layperson giving testimony on the stand.

Statistics

Statistics are summary figures which help you communicate important characteristics of a complex set of numbers. Oftentimes you need numbers to make something clear. For example, if your speech is about using dating apps safely, a good attention getter might be that one in five women in the United States has been raped or sexually assaulted in their lifetime according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center website as of 2022. You can see that this statistic has a greater impact than just saying, “lots of women are impacted by sexual assault.”

You need to think about the best way to deliver the numbers during your speech. Here are some tips when using statistics in your speeches:

- Use them to quantify an idea.

- Interpret statistics to be sure your audience understands them the way you want them to.

- Use statistics sparingly; too many numbers can be confusing for an audience.

- Round off complicated numbers. Instead of saying “3,867,532 people,” you can say “roughly 4 million” or “about 3.9 million people.”

- Identify the source using an oral citation during delivery.

- Explain the statistics with a narrative. The numbers alone do not always tell the whole story.

- Use presentation aids, such as pie graphs, line graphs, or bar graphs to clarify statistical trends. Visual representations can help people make sense of numbers and trends, especially when they are abstract or complex.

Evaluating Your Sources

By now, you know that research is a critical part of the speech-writing process. Using sources throughout your speech is necessary, but you have to decide which sources are the right sources to use. Next, we give you specific ways to evaluate the sources you find during your research.

How to Select Credible Sources and Avoid Biased Sources

Finding information today is easy; it’s all around you. Making sure the information you find is reliable can be a challenge. When you use Google or social media to get your information, how do you know it can be trusted? How do you know it’s not biased? You can feel pretty confident that books you get from the library and articles you find in the library’s databases are reliable because someone has checked all the facts and arguments the author made before publishing them. You still have to think about whether or not the book or article is current and suitable for your project.

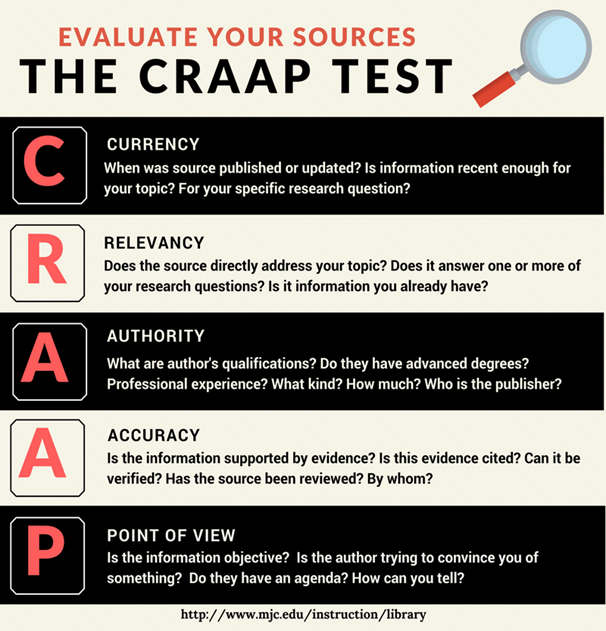

CRAAP Test

Make sure every source you plan on using in your speech outline or research assignment passes the “CRAAP Test,” which helps you identify if the sources use accurate information (Blakeslee, 2004). Since anyone can publish a website or write a blog with a professional-looking design, it’s more important than ever to make sure your sources are legitimate.

Figure 7.4: CRAAP Test4

CRAAP stands for:

- Currency

- When was your source published or updated?

- Is the information recent enough for your topic for your specific research question?

- Relevancy

- Does the source directly address your topic?

- Does it answer one or more of your research questions?

- Is it information you already have?

- Authority

- What are the author’s qualifications? Are they accepted by their peers?

- Do they have advanced degrees or professional experience? What kind and how much?

- Who is the publisher? Are they accomplished and unbiased?

- Accuracy

- Is the information supported by evidence?

- Is the evidence cited?

- Can it be verified that the source has been reviewed?

- Point of View

- Is the information objective?

- Is the author trying to convince you of something?

- Do they have an agenda? How can you tell? Search for links between authors and political / economic organizations.

It is important to identify the good, the bad, and the ugly in our sources so we don’t fall victim to poorly informed opinions. We must also be vigilant about the author’s intent or motivation. If you decide to use a source even though you know it is considered questionable by many experts, make that clear. Today there are some scientists who disagree with the majority of their peers on scientific matters largely considered settled (e.g., humans’ influence on climate change, safety and efficacy of vaccines, the age of the planet and our species, etc.).

If your specific purpose involves explaining an unpopular view, be honest with your audience about that. If you omit the fact, you are being deceptive because you imply that the argument is considered sound. If you don’t discover the fact that your source is not considered credible, your lack of research preparation is also an ethical lapse. Even unintentionally misleading people is problematic. Let’s take a look at some of the different types of information and evaluate their authors’ intent.

Understand the Information

Information is data presented in context to make it understandable (O’Hair, 2019). As a speechmaker, your job is to translate data into understandable information for your audience. For example, vital signs from your doctor are data and your doctor’s interpretation of the vital signs is information that helps put that data into context. Information and data themselves are neutral, but they can have the potential to be skewed.

Propaganda

Propaganda is a term for widely distributed messages designed to manipulate public opinion on an issue, especially difficult-to-sell ideas such as war (Campbell et al., 2020). It often includes “rumors, half-truths, or lies” (Brittanica, 2022) and is often camouflaged as advertising or publicity.

Opposing politicians will often accuse their opponents of using propaganda in their messaging strategies, as they present an opposing political view unfavorably. However, simply casting aspersions on a person or perspective is not propaganda. By nature, propaganda is deceptive, and usually part of a widespread campaign coordinated among many parties. The Nazis in World War II created the most advanced propaganda system in the world up to that point, disseminating untrue information both at home and worldwide to shape others’ views of their actions. One particularly noteworthy incident is known as The Gleiwitz Incident, in which the German Secret Service donned Polish uniforms and took over a German radio station to make the world think Germans were dealing with Polish aggression (Pope, 2018).

Figure 7.5: North Korean propaganda poster 5

Misinformation

Misinformation refers to something that is not true. It is misinforming by using incorrect information. It isn’t always based on an ulterior motive, someone could just get it wrong. The main difference is the intention in which it was used (read on to differentiate misinformation from disinformation).

One author heard a story about two people arguing over COVID-19 statistics. One person was referencing information they had just heard from the most recent cable news story. The other person cited significantly different information based on a webpage they had kept open on their computer. Although it turned out that the webpage referenced hadn’t been updated in months, you can see how misinformation can have an impact on understanding.

Stories change all of the time. The people might get the facts wrong or they may embellish the facts. Let’s be clear, information is complicated and might also be incomplete. The moral of the story is to pay attention as you research! Social media is rife with misinformation as people like and share stories that fit their worldview, often without carefully evaluating them or even reading them. One author shared an image of then-President Trump reading a scholarly, critical book about U.S. media systems on Facebook and was embarrassed when others pointed out that it was a manipulated image; the event never took place.

Disinformation

Disinformation is intentionally stating or circulating inaccurate information. Photoshopped images, doctored documents, or falsified financial records are examples of disinformation (O’Hair, 2019). This must be avoided to be an ethical public speaker. We all watch the news and hear about “fake news.” The question is how do we know what is, and is not, true. Your role as an ethical public speaker is to figure it out for the audience during the research process and offer credible information from beginning to end. Overall, identifying accurate information for our academic research assignments is a process we learn over time. As we learn to research and cite properly, we will become more critical consumers of information.

Now that we have evaluated our sources and are into the writing phase, we need to know how to cite correctly. This next part of the chapter is critical to your speech delivery.

Citing Your Sources Correctly

It is not enough to find good sources in your research, but you have to tell the audience and the readers about them during your speech and in the outline of the speech. Sometimes you may be caught unintentionally plagiarizing just because you are citing incorrectly. Citing means giving credit where credit is due. There are three places to cite for a speech: during the delivery (oral citation), in the outline (in-text citation), and in the References page at the end of the outline.

Oral Citations

Your instructor will most likely ask you to cite sources orally (verbally) during the delivery of your speech. Be warned, this does not mean recite the sources used at the end of your speech or display them on a slide. Cite the sources at the point where you use their information or claims. Also, imagine some audience members may be vision-impaired, others may look away from your slides. An on-screen citation is not an oral citation, and post-speech citations are too late to be meaningful to your audience (or to earn you points). You may be asked to include your oral citations in your outline exactly the way you would say them in the delivery of your speech. Many students believe that this can sound boring; however, these oral citations enhance your credibility as a speaker, making you and your arguments more persuasive.

How to Develop an Oral Citation

When you deliver an oral citation, your audience should believe that the source exists, that you are not making up a source out of thin air. They should have enough information that they can find the source later if they are interested in looking it up to verify your interpretation of its claims. They also should be convinced that the source is credible and authoritative, rather than biased and amateurish.

Oral citations should be written using the following elements (check with your professor):

- Author: Who is it that generated the information? Are they credible? Authors can be organizations—if no individual is listed on your resource, list / name the organization that produced it.

- Date: When did this information get published, updated, or accessed?

- Type of resource: In what form can this information be found? Tell us the name of the place where you found it. Book? Magazine? Online database, video, webpage title, pamphlet, etc.?

- Title: (if there is one)

- Credibility: What credentials does the author or organization have?

If you have described the resource and its producer’s background effectively, your audience will have little doubt that the source exists and is authoritative. After providing these citation elements, you will move into the direct quote or paraphrased information.

Direct quotations: Direct quotes use the exact language from the source without any changes. There are a variety of ways to make clear to your audience that you are quoting material. You can offer the citation elements above, then begin the quotation saying “quote,” and end the quotation saying “unquote.” You could dramatically alter your voice to indicate a change in speaker. You could supplement either of these techniques using your fingers to make quotation marks in the air. You can use careful attribution verbs, like “in her words,” or “the quotation reads,” or “as the author put it.” Do not cite page numbers in your oral citation.

Deciding whether to quote or paraphrase is a creative act. Reasons to quote include transmitting a person’s voice to your audience, maintaining the feeling of the original language, or avoiding misinterpretation.

Paraphrasing: Paraphrasing is a way of writing the research you retrieved in your own words. Sometimes this serves to make research more understandable to your audience. When paraphrasing, you can remove jargon, simplify language, make statements more efficient, modernize vocabulary, and remove potentially offensive or misunderstandable words. Thus, it is sometimes best to change the source’s words into your own words, while still using all correct parts of the oral citation format. Be sure not to alter the essential meaning of the content you are paraphrasing.

These are the most active verbs to use when citing a source. Active verbs are important when you write oral citations. Although there are many you can use, here are a few examples:

- States

- Supports

- Reasons

- Argues

- Asserts

- Reveals

- Estimates

- Suggests

- Cites

- Discusses

- Shares

How to Deliver Oral Citations

Real-Life Example of an Online Fact Sheet (taken from the CDC website)

The Online CDC Fact Sheet entitled Mold, last accessed on March 26, 2022, states, “Stachybotrys chartarum is a greenish-black mold. It can grow on material with a high cellulose content, such as fiberboard, gypsum board, and paper. Growth occurs when there is moisture from water damage, water leaks, condensation, water infiltration, or flooding.” (don’t forget to say “quote” at the start and “unquote” at the end.)

Hypothetical Examples of Oral Citations with Active Verbs

In his recent article entitled “Americans Are Killing Themselves” in the American Journal of Medicine accessed March 15, 2022, Dr. Jorge Ramirez, a cardiologist from the University of Southern California, argues, “Americans are eating foods high in fat in greater numbers than ever before. This builds up plaque in arteries and raises cholesterol. Without change, we will see more Americans die from coronary artery disease.”

According to staff writer Raashid Saaman, in the January 15, 2022 issue of the Los Angeles Times, dogs and cats have been taken in great numbers to local shelters during the COVID-19 pandemic. He reasoned that “most animals were abandoned because people lost income during the pandemic and were unable to afford their basic care, such as food and veterinary care.

(Notice that the three preceding citations have easily recognizable credibility. You might want to explain what CDC stands for, but most people know it, especially after the COVID pandemic. Soon we will approach how to cite sources the audience is likely unfamiliar with.)

Hypothetical Example of Oral Citation from an Article

In an article in the November 2022 issue of the South African Journal of Psychology, Dr. Jada Smith, a professor of sociology at the London School of Psychology, asserts that “Racism begins with exposure to stereotypical and negative attitudes shown by those closest to us. We learn to mirror these behaviors when we are young and by the time we become teenagers, most of these attitudes have evolved into prejudice, and ultimately racism.”

Hypothetical Example of Oral Citation from a Web Page

The web page titled “The History of Apples,” last updated in 2022, provided by the California Apple Advisory Board, reveals varied uses of the apple: as a digestive aid, an antioxidant, and a weight loss aid.

Note: You can say “last updated” or “last accessed on” for any type of oral citation for a website.

Hypothetical Example of Citing a Study

A Harvard University study made available on the Justice website accessed on January 16, 2022, suggests that accidental shootings occur more frequently when people have not had professional firearm training.

Hypothetical Example of Citing a Source that is Not Easily Recognizable or Credibility is Unknown – Website Example

Accessing the website IMDB on February 2, 2022, I was able to trace the motion picture career of George Clooney. For those of you who may not be familiar with this site, IMDB is a web page created in 1990 that specializes in maintaining a history of people and works in the entertainment industry and is used to examine film facts, actors, producers, directors, and dates of various television or movie projects. IMDB reports that George Clooney was “active in sports such as basketball and baseball, and tried out for the Cincinnati Reds, but was not offered a contract” (IMDB, 2022).

Hypothetical Example of Citing a Source that is Not Easily Recognizable or Credibility is Unknown – Periodical Example

The periodical, The Nation, a weekly journal that tends to offer political stories from a left-leaning perspective, suggests in its letters to the editor on March 1, 2022, that facts about the euthanizing of pets in California are simply not true.

APA In-Text Citations

All written academic work needs to cite sources in the outline, both where the information is used and in the References section at the end. The Communication Studies discipline uses the APA format which stands for the American Psychological Association. This formatting style is also used in other disciplines such as Psychology, Linguistics, Sociology, Economics, Criminology, Business, and Nursing. Knowing how to cite in APA format is imperative for all academic writing. This section is based on APA Publication Manual (7th edition) and is designed to help you learn how to format in-text citations. In-text citations are used when quoting directly and when paraphrasing from a research source.6

The APA Basics

- In-text citations in APA follow the author-date method.

- If you are directly quoting a work, you need to include the author, publication year, and also the number of the page from which you are quoting. Use the term “p.” for one page and “pp.” if the quote spans multiple pages. Be sure to add a space after the p, like this: “p. 32” or “pp. 2-5”.

- If you are paraphrasing a work, or simply referring to an idea from a work, you need to include the author and publication year, but you don’t need to include the page number (though it is encouraged to include page numbers when paraphrasing or summarizing to help readers locate that information).

Creating In-Text Citations with a Signal Phrase

- When creating an in-text citation, you can use what’s called a signal phrase to introduce a quotation or begin paraphrasing within the text of the sentence.

- A signal phrase calls attention to the author. This is the most pronounced, marked way to cite a source.

- The signal phrase contains the author’s last name followed by the publication date in parentheses.

- If you use a signal phrase to introduce a quote, you will need to include the page number in parentheses directly after the quote.

- Examples of in-text citing with a signal phrase:

- Research by Newsom (2004) suggests “Sailor Moon’s greatest powers are eventually revealed as related to her capacity to love, and through that love to heal” (p. 10).

- Newsom (2004) finds that Sailor Moon “illustrates the quality of love very plainly throughout the anime” (pp. 67-68).

- According to Newsom (2004), Sailor Moon’s power is derived from her emotional capacity.

Creating In-Text Citations without a Signal Phrase

- If you don’t use a signal phrase to introduce a quote or begin paraphrasing within the text of a sentence, you will need to place the author name, publication date, and, if applicable, the page number in parentheses directly after the quote or paraphrased content.

- Examples of in-text citing without a signal phrase:

- Sailor Moon is often portrayed crying, which supports the argument that emotions are central to her character (Newsom, 2004)

- One scholar states, “Sailor Moon’s greatest powers are eventually revealed as related to her capacity to love, and through that love to heal” (Newsom, 2004, p. 10) and goes on to illustrate how the character’s love is physically expressed.

When citing without a signal phrase, authors (you!) are focusing attention on the information, rather than the author of the source behind the citation. This technique is common when asserting a list of facts produced in different sources, or when supporting information that is relatively well known and non-controversial, but you want to be clear where you found it.

- Examples:

- Conversational narcissism behaviors include boasting (Vangelisti & Knapp, 1990), “shifting the conversational focus to the self” (Horan et al., 2015, p. 156) and interrupting (Blake, 2001).

- Martin Luther King Jr.’s I Have a Dream speech was protesting conditions for African Americans in the United States (Lei & Miller, 1999).

In-Text Citations with Multiple Authors

- In-Text Citations for Sources with 2 Authors:

- Place “and” between authors’ last names when providing them in the text of your sentence with a signal phrase.

Example: Langford and Speight (2015) state…

- Place “&” between authors’ last names when providing them in parentheses after the quote or paraphrased content.

Example: …(Langford & Speight, 2015).

- In-Text Citations for Sources with More Than Two Authors:

- Place “et al.” after the first author’s last name when providing it in the text of your sentence with a signal phrase.

Example: Ince et al. (2017) claim…

- Place “et al.” after the first author’s last name when providing it in parentheses after the quote or paraphrased content.

Example: …(Ince et al., 2017)

In-Text Citations When Citing Multiple Works

- In-Text Citation with More Than One Work:

- Some of the ideas you cite will be pulled from more than one source, so you will need to include multiple sources in your in-text citations.

- To cite multiple works in your in-text citation, place the citations in alphabetical order by the first authors’ last names and separate the citations with semicolons.

- Example: Educational psychology is the most researched field involving human learning (Holloway & Hofstadt, 2000; Olson, 2019; Sterling & Cooper, 2020).

- In-Text Citation if One Work is the Most Directly Relevant:

- Place the most relevant citation first, then insert a phrase such as “see also” and the other works

- Example: Educational Psychology does not support learning styles (Palmer, 2020; see also Horne, 1999; Hayward, 1993)

In-Text Citations for Indirect Sources

- If you want to cite a source (an original source) that was cited in another source (a secondary source), name the original source author(s) in the text as you would with a signal phrase. List the secondary source in your reference list and include the author, date, and page number in your parenthetical citation, preceded by the words “as cited in.”

Example: As John Dewey said, “Action is the test of comprehension. This is simply another way of saying that learning by doing is a better way to learn than by listening” (as cited in Waks, 2011, p. 194).

In-Text Citations for Sources without Page Numbers

- Some sources, especially electronic ones such as webpages, may not have page numbers that you can include when creating in-text citations for quotes.

- If the source you are quoting doesn’t have page numbers, provide some other piece of information that will help readers locate the quote.

- You can use chapter names or numbers, heading or section names, paragraph numbers, table numbers, verse numbers, etc.

- Examples of in-text citing sources without page numbers:

- “In E.T., Spielberg made a truly personal film, an almost autobiographical trip back into his own childhood memories” (Breihan, 2020, para. 6).

- To prevent kidney failure, patients should “get active” and “quit smoking” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017, “What Can You Do” section).

APA Reference Page Citation Format

The reference page is simply a list of all the sources used in the outline. This page is titled “References” and will be the last page of your outline. Each source will be listed in alphabetical order by author’s last name or by organization’s name (if there is no individual author). Each citation will be double spaced and there are specific ways they will need to be listed.

Reference List Basics

- List your sources in alphabetical order according to the last name of the first author of each work.

- Double-space the entries and use hanging indents.

- Adhere to the proper citation format for each source type.

Formatting Author Names

- Use surname followed by the author’s initials: Author, A. A.

- If the author’s given names are hyphenated, maintain the hyphen between the initials:

- Example: Ai-Jun Xu would by Xu, A.-J.

- Use commas to separate suffixes such as Jr. and III: Author, A. A., Jr.

- Write the surname exactly how it appears, including hyphenated surnames and two-part surnames: Santos-Garcia, A. A. or Velasco Rodriguez, A. A.

- If the author is an organization, just use the organization’s name; do not rearrange the organization’s name in order to give it a surname.

- If you can discover no author, not even a company or government agency, move the title of the work to the author position. Do not use Anonymous unless the work is signed as Anonymous.

Formatting Titles

- Capitalize only the first letter of the first word and proper nouns.

- If it is a two-part title, capitalize the first word of the second part as well (e.g., after a colon or period).

- Names of journals and books are italicized while article titles and book chapter titles are not italicized

Citation Style for Commonly Used Sources

- Journal Article:

Format:

Author’s Last Name, First Initial. Second Initial If Given. (Year of Publication). Title of article: Subtitle. Title of Journal, Volume Number (Issue Number), first-page number-last page number. DOI

Examples:

Without DOI

Schott, C. (2020). The house-elf problem: Why Harry Potter is more relevant now than ever. Midwest Quarterly, 61(2), 259–273.

With DOI

Takhtarova, S. S., & Zubinova, A. Sh. (2018). The main characteristics of Stephen King’s idiostyle. Vestnik Volgogradskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta. Seriâ 2. Âzykoznanie, 3, 139. https://doi.org/10.15688/jvolsu2.2018.3.14

- Book:

Format:

Author’s Last Name, First Initial. Second Initial If Given. (Year of Publication). Title of book: Subtitle if any. Publisher.

Example:

Manson, M. (2019). Subtle art of not giving a f*ck: A counterintuitive approach to living a good life. Newbury House Publishers.

- Chapter in an Edited Book:

Editors are listed in the citation of an edited book. Their names are not inverted and come after the title of the book chapter. Place “In” in front of the first editor’s name. If there is only one editor listed use (Ed), if more editors are listed use (Eds.) after the last name of the editors.

Format:

Author’s Last Name, First Initial. Second Initial If Given. (Year of Publication). Title of the book chapter. In First Initial. Second Initial. Last Name & First Initial. Second Initial. Last Name (Eds.), Title of the book (Edition or volume number if given, pp. #-#). Publisher.

Example:

Zasler, N. D., Martelli, M. F., & Jordan, B. D. (2019). Civilian post-concussive headache. In J. Victoroff & E. D. Bigler (Eds.), Concussion and traumatic encephalopathy: causes, diagnosis, and management (pp. 728–742). Cambridge Univ Press.

- Webpage:

Format:

Author’s Last Name, First Initial. Second Initial If Given. (Year of Publication, Month Day if given). Webpage title. Organization If Given. http://website.com

Example:

Horowitz, J. M., Igielnik, R., & Parker, K. (2018, September 20). Women and leadership 2018. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/09/20/women-and-leadership-2018

Conclusion

This chapter focused on supporting your ideas with credible evidence. Although it wasn’t the most exciting chapter, this is one of the most crucial elements of speech writing and speech delivery. Sometimes students think that doing a quick Google search and jotting notes into an outline means they are writing a speech. We hope you see the value of oral citations–convincing your audience that your sources are real and credible. We also hope that after reading this chapter you see that academic research is easier than you thought. Many run away from academic research or drop a class when they see a research paper in the syllabus, but if you apply the right tools for uncovering information, it can make your job simpler. Don’t drop your class because it says you have a research assignment! You can do it and your college provides you with all of the tools you need to be a successful researcher. Research doesn’t only happen when you are scrolling your former schoolmates and partners on social media, it happens every time you read a published piece of evidence. Now go impress your professors!

Reflection Questions

- After visiting your campus library’s databases, which of them do you believe will be the most relevant for your informative and persuasive speech assignments?

- Why is it important to consider using peer-reviewed sources for an academic speech?

- How will you test the credibility of your sources?

- Why do audiences appreciate oral citations?

- Why should you cite sources when you use them–orally during the speech and in-text in the outline–and not simply rely on sharing a list of resources at the end of the piece?

- Why is it important to use active verbs when you write oral citations?

Key Terms

Brief Example

Direct Quote

Disinformation

Expert testimony

Hypothetical example

Information

Lay testimony

Misinformation

Oral Citation

Paraphrasing

Peer-reviewed

Popular sources

Propaganda

Scholarly sources

Secondary sources

Specific instance

Statistics

Substantive sources

Testimony

References

APA Formatting and Style Guide (7th Edition): General Format (n.d.). Purdue University Online Writing Lab, Retrieved March 4, 2021 from https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/general_format.html.

Blakeslee, S. (2004). The CRAAP Test. LOEX Quarterly, 31 (3): 6–7.

Campbell, R. C., Martin, C., Fabos, B., & Harmsen, S. (2020). Media Essentials., 5th edition.

Get Started With Research: Popular, Substantive, and Scholarly Sources. (n.d.). Modesto Junior College Library, Retrieved December 4, 2021 from https://www.libguides.mjc.edu/ResearchHelp/sources.

O’Hair, D., Rubenstein, H., Stewart, R. (2019). A Pocket Guide to Public Speaking. Bedford/St. Martin.

Pope, C. (2018). How a false flag sparked World War Two: The Gleiwitz Incident explained. Retrieved January 23, 2022 from https://www.historyhit.com/gleiwitz-incident-explained/.

Smith, B. Lannes (2021, January 24). Propaganda. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved May 15, 2022 from https://www.britannica.com/topic/propaganda.