2 Chapter 2: Ethics

Lauren Rome, College of the Canyons

Adapted by William Kelvin, Professor of Communication Studies, Florida SouthWestern State College

|

LEARNING OBJECTIVES |

|

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

|

Figure 2.1: Ethics1

Introduction

The explosion of the internet and the constant presence of media have made it impossible to avoid receiving messages. We see messages when we look on social media, when we attend class, when we watch the news, and even when we talk to our friends. I’m willing to bet you haven’t once asked yourself, “are these messages ethical?” And why would you? We don’t tend to live our lives constantly asking ourselves that question. We do, however, ask ourselves if we believe and agree with the information. Both of these questions correspond to the principles of ethical public speaking. Throughout this chapter, we will examine ethics in public speaking, and how it relates to your upcoming speeches.

The Importance of Ethics

When it comes to public speaking, your goal is to communicate a message to your audience. In many cases, this could mean you are simply conveying information and sharing knowledge; other times this could mean you’re actively persuading your audience to change their minds, behaviors, or beliefs. As the person communicating the message, you are tasked with a significant ethical dilemma, whether you are aware of it or not.

In general, ethics examines what society deems as issues of morality, such as what is right, fair, or just. When looking at ethics from a personal standpoint, it guides how you “should” behave in various situations. History is ripe with great speakers who used ethical and passionate messages to make a positive impact or bring people together. Some examples include Martin Luther King Jr., Malala Yousafzai, Mohandas Gandhi, and Maya Angelou. On the other hand, there are cases of notorious speakers who used the power of public speech unethically, bringing about chaos, destruction, or heartbreak. Infamous speakers like Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Vladimir Putin, and Joseph McCarthy serve as stark reminders of the harm of unethical public speech.

Ethical Responsibilities of the Speaker

When choosing to use your voice in a public setting, you will face many ethical considerations because you are speaking to actual people, the audience. As such, you need to make careful decisions when determining your goal, your word choice, how you will accomplish your goal, and giving credit where it is due. Ultimately, ethics in public speaking is about conveying messages honestly, thoughtfully, and responsibly.

Identify Your Speech Goals

Ethics places emphasis on the means used to secure the goal, rather than on achieving the goal, or end, itself. Any audience will be more receptive to your message if you use ethical standards to determine your speech goals. Think about why you are speaking to the audience and what you hope to accomplish. This will allow you to choose the most ethical strategies for achieving your goal.

Have you ever tried asking someone for a favor? Maybe you needed your sibling or roommate to take out the trash. The goal is to get them to complete the task for you, but what method will you use to accomplish this goal? One way may be to explain how busy you are working on an outline for your upcoming speech. Another example would be to strike a deal and offer to take the trash out twice in a row. Or, you could guilt them into taking out the trash because they borrowed your computer last week. Finally, you could lie and say you feel unwell and so you are unable to take the trash out. Any method has the potential to bring about the result, but I’m sure you’re able to identify which paths feel the least ethical; no one likes to be guilted or tricked into doing something.

Send Honest Messages

Have you ever heard the saying “honesty is the best policy?” Although this is most often associated with people telling lies, it also applies to the messages you choose to send in your speeches. Ethical speakers do not deceive their audience. Instead, they present verifiable and researched facts. Ethical speakers should not disguise opinions as fact. All content must come from a place of authenticity. Authenticity builds credibility.

Credibility is a complex concept with several facets. In public speaking, credibility is often referred to as the ancient Greek word ethos, which includes your competence, based on your authority and currency on a subject, as well as your trustworthiness. It’s something that is built through your words and actions. Credibility can become damaged when it is revealed you have either lied or even just slightly bent the truth in your speeches.

Once lost or damaged, credibility is nearly impossible to recover or repair, both during a speech and in life. Build it and treasure it. History is full of examples of people’s credibility eroding seemingly overnight. One recent example is George Santos, a young man who was elected to Congress based on narratives later determined to be mostly false. Many people who voted for Santos felt duped by his fabrications and some within his own party called for his resignation.

Choose Language Carefully

It might be obvious you’re going to use words to communicate messages. Less obvious, is the significance these words hold for your diverse audience who are the focus of your speech. Oftentimes, the speaker thinks of themselves in speechmaking, however, you should be focused on the audience at all times.

Speaking ethically involves striving to use inclusive language, aimed at making all listeners feel represented in the language of the speech. At a minimum, inclusive language avoids the use of words that may exclude or disrespect particular groups of people. For example, avoiding gender-specific terms like “man” or “mankind.” Inclusive language also avoids statements that express or imply ideas that are sexist, racist, otherwise biased, prejudiced, or denigrating to any particular group of people. Even if the speaker means well, certain terms, especially around attributes of identity, can be interpreted as offensive, hurtful, outdated, or inappropriate.

A simple strategy to make people feel included in your speech is to use the plural pronouns “we” and “us” instead of the singular pronouns “I” and “me.” When you linguistically separate your audience from yourself, you create a divide, but when you use words to show your connection, you come together. Imagine the difference in audience reception to “Today I will tell you…” versus “Today we will cover….” This situation can be exacerbated when audience members have some knowledge on the topic. If you treat your audience as complete novices, any members experienced in your topic may feel offended.

Avoid Plagiarism

When we speak ethically, we use our own original speech content. That doesn’t mean you have to come up with the facts and evidence on your own. Just as with any other research project, you must give appropriate credit for the sources used. A good rule of thumb is, “If you didn’t write it, cite it!” Be sure to read closely the Citing Your Sources Correctly section in Ch. 7, Gathering Materials & Supporting Your Ideas. When you cite your sources, you avoid plagiarism, which is passing off other people’s work as your own. Plagiarism can have serious consequences, like failing an assignment, failing a course, or even being kicked out of the educational institution. This occurs in two ways: intentional plagiarism and unintentional plagiarism.

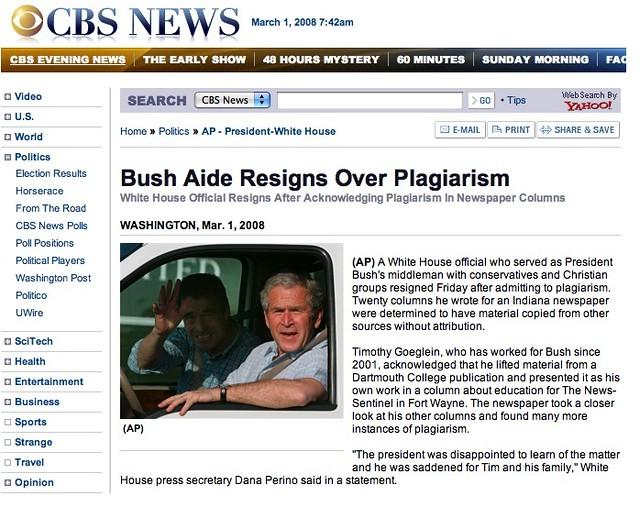

Figure 2.2: Bush Aide Resigns Over Plagiarism2

Intentional plagiarism is when a speaker purposefully uses content that is not their own. The most egregious example is when someone steals an entire speech or paper and just slaps on their name. Some other instances of intentional plagiarism include: when someone fabricates sources or quotes; strategically changes a few words from a source without citing it (proper paraphrasing requires more than just changing a few words from the original source); or purposefully adds sources to their references that they didn’t use.

Something that happens more commonly is unintentional plagiarism, which occurs inadvertently. Think about what we mentioned at the beginning of the chapter, with how we are constantly taking in messages. Watching a documentary on Netflix does not make you an expert. Although it may be a great place to start building your knowledge, it doesn’t mean it is your intellectual property. That information still came from a source (the documentary), and you’ll need to cite it. Unintentional plagiarism can also occur if we use the same paper for two different classes, quote a source incorrectly, or fail to properly introduce an idea we’ve learned from someone else.

It doesn’t matter whether you meant to be intentional or unintentional, plagiarism is still unethical and can have serious consequences. There are many examples, such as a U.S. professor stepping down from a lucrative vice-chancellor position for plagiarizing passages of a grant application. A political appointee in Germany was compelled to resign from her prestigious post as minister of education and research 40 years after publishing a doctoral dissertation containing many passages with insufficient citation.

To avoid plagiarism, spend time conducting quality research and keep careful notes. Use quote marks to indicate material that is copied verbatim in your own notes so that you avoid passing the material along as paraphrased when it is not. Don’t forget to orally cite your sources in the delivery of your speech at the moment you utilize them. Also, every source cited in your References should be cited in the text of your outline at the places where you use the information. Oral citations during the speech and in-text citations in the outline are both important to avoiding any charges of academic misbehavior.

Be Prepared to Speak

Speech preparation entails picking and researching a topic, analyzing your audience, organizing your main points, creating visual aids, and practicing your delivery. You prepare so that your speech can have the greatest impact. As a speaker, it is your responsibility to consider the impact of your speech and to ensure you are communicating truthful, accurate, and appropriate information. From an ethical standpoint, preparation is crucial to ensure you are thoroughly informed about your topic and allows you to convey a sense of credibility to your audience.

When you are unprepared, you will be embarrassed and your audience will feel that you are wasting their time. Also, plagiarism is often a consequence of procrastination. Preparing well before deadline means you won’t be tempted to recite others words or ideas without proper attribution.

Ethical Responsibilities of the Listener

As you’ve seen throughout this chapter, careful consideration is taken by the speaker to craft a thoughtful and developed speech for their audience. In return, the audience should also behave ethically. When thinking about these responsibilities, identify the expectations you have for an audience when you’re speaking. Do you want them to listen with an open mind? Pay attention to you? Demonstrate respect? Of course, you do, but let’s be honest for a second…do you always listen to messages that way? It is really easy to say we are listening ethically, but this can be harder to apply when we are distracted or unprepared for listening. If this sounds like you, there are several strategies covered in chapter 4.

Figure 2.3: Ethics Committee3

Be Prepared to Listen

When you find yourself seated in an audience about to listen to a speaker, how do you prepare? Do you tell yourself that you will be actively listening to the speaker for a certain number of minutes? Do you remind yourself to listen with an open mind? Or, do you sit there on your phone, mindlessly scrolling social media? Only one of these examples is common practice, but the others can make a huge difference in how much you take away from a speech. By telling yourself you are committed to listening to the speaker, you won’t be inclined to give in to distractions, or let your mind wander.

Avoid Prejudging and Keep an Open Mind

Unless you are watching a recorded video of a speech, you will never see or hear the same speech twice. Take it from us public speaking teachers who have heard the same speech topic countless times. Even if you think you know what the speaker is going to say, or you think you know more about a topic than the speaker, you can always learn something new. If you spend any time thinking about anything other than listening, you are bound to miss valuable information that will make you an ill-informed listener.

Be Courteous and Pay Attention

It’s simple: treat others how you would like to be treated. Who do you want to see when you are speaking to an audience? Be that person. Pay attention to your body language when sitting in an audience. What do you consider ethical body language?

Information communication technologies (ICTs) such as cell phones and laptops have made it difficult for people to focus and easy for them to be distracted. Silence your cell phones before every class. Keep your phone put away unless you absolutely need it. Likewise, do not have a laptop open during your peers’ performances. Chances are, you’re not taking notes. Looking at screens during speeches is disrespectful. Mastering the art of being in the moment can separate you from your peers in business, politics, and even personal relationships. This lesson will apply beyond the classroom. No matter your future social environments, listening attentively to others will improve your social standing, while allowing yourself to be seduced by screens will make others think you do not value their contributions.

If a speech is not capturing your attention, ask yourself what could have been done better, perhaps jotting down a few notes (paper notes will not make you look inattentive the way a screen will, even if you’re using it for a good reason) to share constructive feedback with your peers later. Even if you do not share the notes, imagining ways to spice up someone else’s speech will make you a better writer and speaker.

Providing Feedback

Public speaking instructors often ask students to provide their classmates with feedback on their speeches. Of course, you have to be paying attention if you are going to ethically provide feedback. Saying “Great job!” or “You did great” is not ethical feedback. Providing feedback to your classmates means that you are supplying them with useful comments about things they did well and/or things they could make stronger in future speeches.

Tasha Souza, a professor at Boise State University who researches classroom practices, taught one of your authors a simple approach to feedback—”gems and opportunities.” Gems are things the speaker did well. Opportunities identify areas for potential improvement. We all love to hear praise, which is good for our self-esteem, but we can’t advance without people letting us know about weaker aspects of our performance. For this reason, the most ethical feedback always helps us feel good, but also helps us move forward. No speech is without merit—we can all find gems in any performance (even our own, as painful as they may be to watch when recorded!). And, no speech is perfect—ask your instructors, most rarely give 100% scores on speeches. So, even when your classmates perform great, you should be able to find more opportunities for them to improve. The highest performers will be eager for such feedback.

Avoid Distractions

Taking care of your body is an important part of being a good listener. Get a good night’s sleep before speech days—even others’ speech days. If you are dozing during someone’s speech, they may think you find them boring, decreasing their self-confidence, or worse, they may be distracted by your fitful motions and lose their concentration. Likewise, make sure you are not starving when class starts. if your belly is rumbling, you cannot focus, and if others hear it, it could distract them, too!

Conclusion

At the end of this chapter, we hope you see the importance of ethics as it pertains to public speaking. Ethics impacts the speaker and the audience, alike. Being honest, thoughtful, respectful, and prepared are the key ingredients to being an ethical public speaker. It is up to you to build your credibility and be a strong speaker. It may not be easy to be ethical, but it is right.

Reflection Questions

- What speakers have you heard speak that you felt were particularly ethical in their speech and why would you say their performance was ethically sound?

- Give an example of a public speaker behaving unethically. What behaviors in your example are problematic and why do you consider them unethical?

- Have you ever questioned the credibility of a speaker? What did they say that made you question their credibility? Did you question their competence, ethics, or both, and why?

- What do you know about plagiarism now that you didn’t know before? If you did not learn anything new, which aspects of plagiarism do you think novice speakers should be most cautious about?

- Which aspects of being an ethical listener do you hope to achieve in this class?

Key Terms

Credibility

Ethics

Inclusive language

Intentional Plagiarism

Plagiarism

Unintentional Plagiarism