3 Chapter 3: Speaking with Confidence

Lauren Rome, College of the Canyons

Adapted by Katharine O’Connor, Ph.D., Florida SouthWestern State College

|

LEARNING OBJECTIVES |

|

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

|

Figure 3.1: You Got This1

Introduction

Picture this: it’s the first day of class and your professor is going over the syllabus. You find out that you’ll have to give a final presentation at the end of the semester. Does your heart start racing? Do you consider dropping the course? If you answered yes, then you are not alone. Many people fear public speaking, with some even citing this as their worst fear…even more than death! A famous quote from the comedian Jerry Seinfeld is “According to most studies, people’s number one fear is public speaking. Number two is death. Death is number two. Does that sound right? This means to the average person, if you go to a funeral, you’re better off in the casket than doing the eulogy.”

Although we might not be thrilled about it, we are going to have to speak to people in different capacities throughout our lives. You will have coworkers, family, friends, and acquaintances, all of which you’ll be communicating with, in some form or another.

In order to effectively communicate, we need to understand what is triggering our fears surrounding speaking and identify strategies for reducing the anxiety we feel. Throughout this chapter, we will explore the basics of communication apprehension, common myths associated with public speaking, and how to reduce the effects of communication apprehension.

Communication Apprehension

According to Professor James McCroskey (1982), communication apprehension is a broad term used to describe “the anxiety or fear related to real or anticipated communication with others” (p.137). While communication apprehension is most commonly associated with public speaking, it can also be the anxiety associated with speaking to a small group, or just to one person.

Ultimately, everyone experiences different levels of communication apprehension when it comes to public speaking. Maybe you feel a gripping fear just being enrolled in a public speaking course, or you feel a slight knot in your stomach right before you give a speech. No matter what level of communication apprehension you feel, there are many ways to explain where it stems from, and strategies you can use to reduce its effects.

Identifying Sources of Communication Apprehension

Think back to the story at the beginning of the chapter. If you related to feeling anxious just at the thought of giving a speech, did you take time to think about why you felt that way? It’s easy to identify when we experience a feeling, but it’s a lot harder to think about the underlying cause of that feeling. To better understand why we feel anxious about public speaking we first have to determine the source of communication apprehension.

- Inexperience – There is a reason why public speaking is one of the first classes you’re advised to take in college. If you’ve never taken a class on it, how will you know how to execute it effectively? Just like with any other class (math, computer science, cooking, auto technology, etc.), you need to learn the skills before you can apply them.

- Unrealistic expectations – When we think about giving a speech, we put a lot of pressure on ourselves. We expect our speeches to “be perfect.” But, expecting perfection is an unrealistic goal, even if you’re an experienced public speaker. Preparation, you’ll soon learn, is drastically different from perfection, and is a much more attainable goal.

- Previous experiences – I have heard countless stories from students who have had bad experiences when it comes to past performances like embarrassment, a bad grade, memory lapse, etc. You might attribute these bad experiences not only to unrealistic expectations but also to a lack of preparation. Typically, trauma doesn’t repeat itself if you prepare. Lack of preparation tends to be the culprit of the trauma.

- Overthinking – This last source of apprehension encompasses many of the underlying fears we have about public speaking. So often, students tell themselves that the audience is looking at them and judging them when they are speaking. Or, they think they might make a mistake and that means they’ve ruined their speech. All of these internal thoughts are actually myths (soon to be debunked) that just add unnecessary pressure on the speaker. Let’s avoid mental gymnastics! Any time spent thinking about things other than speech preparation will add to the apprehension you’re feeling.

Many of these sources of apprehension aren’t grounded in reality. Next, we will debunk many of the myths and misconceptions about public speaking. Then, we will give you strategies you can apply to reduce your apprehension.

Common Public Speaking Myths

Every semester, students express their concerns associated with public speaking, whether these are “tips” they’ve heard from friends or misconceptions they’ve been led to believe. Many of the common concerns identified are entirely made up in their own heads or, upon closer inspection, can be easily explained by other factors. Let’s take a look at the most frequently cited concerns among beginner speakers.

“You will look as nervous as you feel.” Simply put, no one will know you’re nervous unless you tell us. Any and all physiological responses to nerves, a flushed face, sweat, or shaking hands, might be attributed to outside factors. Maybe you just had to jog up a flight of stairs or you had too much coffee. Some of the most effective speakers will return to their seats after their speech and exclaim they were so nervous. Listeners will respond, “I had no idea!” Audiences do not necessarily perceive our fears. Consequently, don’t apologize for your nerves. In fact, don’t even mention it. There is a good chance the audience won’t notice if you don’t point it out to them.

“Audiences are just sitting there judging you.” In general, students in a public speaking class will be able to empathize with you in a way that you might not see in any other kind of class. In a public speaking class, your audience is in the exact same position as you. They want you to succeed! Similarly, in most situations, audiences are actively choosing to be there, or are present because it is relevant to them. In these cases, the information is their focus; they will be listening, not judging.

“Any mistake means that you have ‘blown it.’” Have you ever said the wrong word when speaking? I can attest to mixing up words every now and then. Recently, I was trying to say, “informative speech workshop sheet” to my class, but instead, I said, “informative speech worksheet shop.” That didn’t make much sense, of course, so I paused and corrected my words before moving on. Mistakes like this happen all the time, which is part of what makes us human. What matters isn’t whether we make a mistake, but how well we recover. A speech does not have to be perfect. Speakers who can identify when they’ve made a mistake and work to correct that misspoken word or information are demonstrating two things: first, you’re a human – yay! Second, you are a present speaker. Being present in your speeches allows you to connect with your audience and ensures you are effective in communicating your message.

“Avoid speech anxiety by memorizing your speech word for word.” Contrary to popular belief, memorizing your speech word for word is not required, and has a greater potential to increase your anxiety. Instead of having a strong general understanding of the information you want to share and allowing yourself flexibility in word choice, memorizing adds unnecessary pressure to say things in a precise way. This can impact your delivery, making your speech sound robotic, monotone, or come out of your mouth at warp speed. In reality, your audience has no expectations of what you plan to say and would prefer a more natural, and engaged speaker rather than a robotic, calculated speaker.

“Imagine the audience is naked.” Just. Don’t. Do. This. It is not going to help you, and in fact, will take away from where your focus should be: your speech! The audience is not some abstract image in your mind. It consists of real individuals who you can connect with through your material. To “imagine” the audience is to misdirect your focus from the real people in front of you to an “imagined” group. What we imagine is usually more threatening than the reality that we face.

“A little nervousness helps you give a better speech.” This “myth” is actually true! Professional speakers, actors, and other performers consistently rely on the heightened arousal of nervousness to channel extra energy into their performance. People would much rather listen to a speaker who is alert and enthusiastic than one who is relaxed to the point of boredom. Many professional speakers say that the day they stop feeling nervous is the day they should stop speaking in public. The goal is to control those nerves and channel them into your presentation.

Reducing Public Speaking Anxiety

Experiencing some nervousness about public speaking is completely normal. Whether you are worried about doing your best, not messing up, or effectively communicating your message, it means one thing: you care! To help reduce any apprehension you may be feeling, we have categorized these strategies into three main parts: Prepare, Practice, and Present.

Prepare: Setting Up for Success!

We all know that we have to prepare for day-to-day activities. We set goals and expectations, do research, and/or write a to-do list. Think about when you prepare for a trip. You don’t just show up at the airport and buy a plane ticket; you plan the trip. Let’s connect this to public speaking. Preparing is adapting; here’s how:

- Set realistic expectations – Thinking that perfection is an option, means you’re setting yourself up for failure. Aiming for perfection doesn’t allow for mistakes, which means if they happen, you won’t be prepared for them. So, set realistic expectations. For example, don’t expect that you’re going to research and write your speech in one day. Change your mindset and embrace the fact that you are going to speak and take control of your preparation.

- Know your audience – Thinking about who you are speaking to will help you in choosing a topic and finding ways to connect with them. Think back to the first few “introduction” assignments…what do you know about your classmates?

- Organize your ideas – Unfortunately, you won’t have unlimited time to speak to an audience. This means you have to find a focus for your speech and determine what you want to say.

- Don’t procrastinate writing your outline – Procrastinating will only add to your anxiety and can sometimes even be the cause. Remember, your outline is a work in progress; you are meant to edit and revise throughout the process. Don’t let this hang you up.

- Prepare well – There is a direct connection between how nervous you feel and how much you’ve prepared. Plan to spend time preparing and practicing your speech as these are two of the strongest ways to minimize apprehension and anxiety.

Practice: Just Do it!

Yes, a plan can reduce your initial anxiety, but practicing can have an immediate effect and give your confidence a quick boost. Here is a practicing to-do list:

- Recreate the speech environment – As best you can, imitate the environment in which you’ll be speaking.

- Visualize success – Imagine yourself giving the speech successfully, rather than imagining all of the mental gymnastics. Stop overthinking!

- Practice out loud – Say your speech out loud when rehearsing. The first time you deliver your speech out loud should not be when you are officially delivering your speech in class. You might even voice or video record it to hear how it sounds.

- Minimize what you memorize – Memorizing doesn’t work, but you can memorize the first two sentences of your introduction if you think it will help you get started when you step up in front of the audience. After those two sentences, you need to merge into a more natural speaking style.

Perform: It’s Game Time!

You’ve prepared, you’ve practiced, and you’re ready to go. Here are some simple strategies to employ right before and during your speech delivery.

- Nervousness isn’t visible – Keep in mind that most listeners won’t even be aware of your anxiety. They often don’t see what you thought was glaringly obvious.

- Channel your energy – There is no physiological difference between nervousness and excitement; it’s all in how you define it. Tell yourself you are excited and looking forward to sharing this important information. Allow your natural body responses to help you be a more natural and dynamic speaker.

- Think positively – Have you ever heard of a self-fulfilling prophecy? What you expect to happen may be exactly what does happen. So remind yourself that you are well-prepared. Then, imagine yourself speaking clearly and effortlessly. Remember, you are an expert on your topic! You’re going to share fascinating information with them.

- Focus on the message rather than fear – It is easy to focus on fear, but it will make you more fearful! Trust us, if you continue to think about what you are saying rather than how you are saying it, you will take control of your anxiety.

- Breathe – Remind yourself that you are calm and in control of the situation and be sure to take a deep breath whenever necessary. Even just sitting in your chair during class and taking slow and deep breaths can help calm your body. In through your nose, and out through your mouth….

- Embrace eye contact – You might think, “everyone is going to be staring at me and judging me.” Instead, remember that everyone is looking at you because they are actually listening and interested in what you have to say. (And their professor told them to!) Find a couple of friendly faces and focus on them. If they’re sending positive energy your way, grab it!

- Fake it until you make it – You might think this too good to be true, but it can work for beginners. You know what a strong public speaker looks and sounds like, so be what you know you can be!

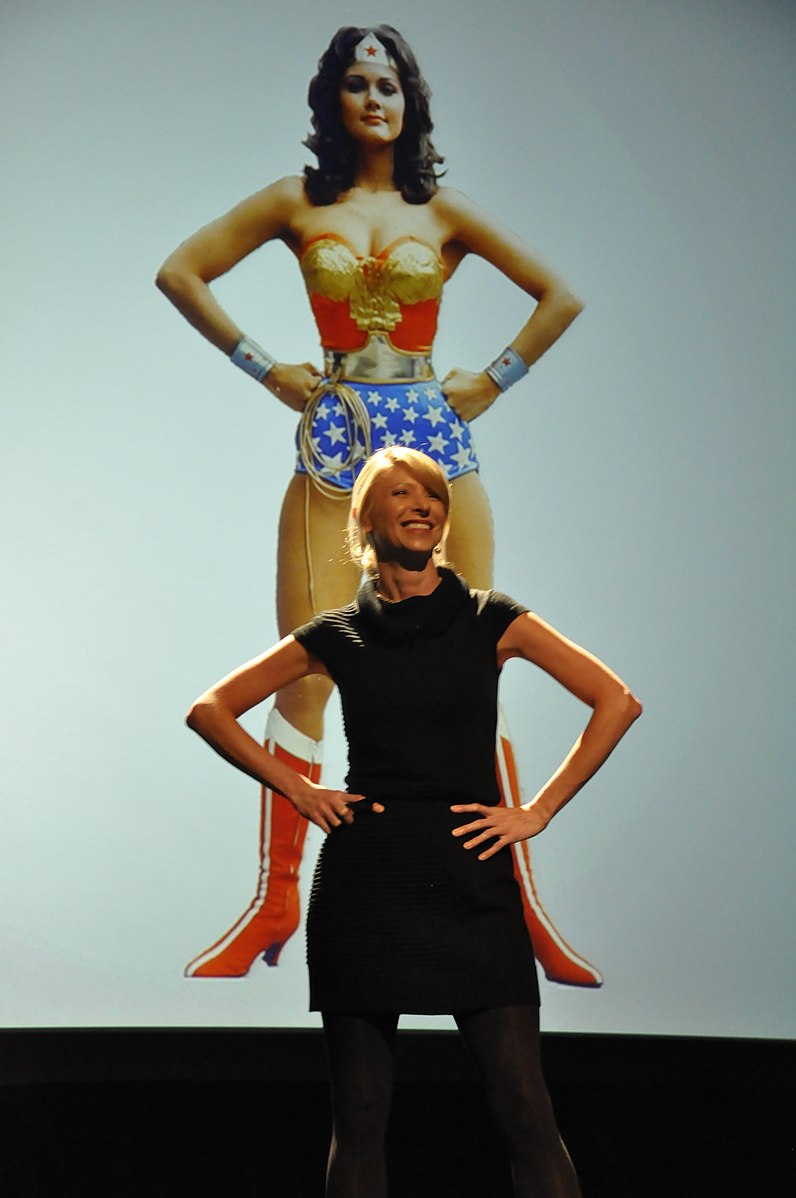

- Try power posing – This life “hack” is where you pose your body in powerful positions; standing tall, hands on your hips, head up, feet wide, and making yourself appear large and powerful. Putting yourself in what you define as a powerful stance can make you feel more powerful and confident. So stand up and do it. Yes, right now!

Figure 3.2: Power Posing2

- Be yourself – The most important rule for communicating effectively is to be yourself. The emphasis should be on the sharing of ideas, not on the performance. Strive to be as genuine and natural as you are when you speak to family members and friends. Lean in to what you already know how to do.

Conclusion

Are you feeling more confident yet? We hope so. In this chapter, we defined communication apprehension and different sources that create anxiety. We also discussed strategies to help you combat these anxieties; some big, and some small. These are all things you already know how to do. It is as simple as thinking positively and visualizing success. All of these elements can be used right now, today, and really can change your attitude towards public speaking. Remember, nervousness when speaking in public is normal. It is how you manage it that moves you from a novice speaker to an experienced one. Remember: breathe in and breathe out.

Reflection Questions

- How does your body respond to communication apprehension?

- Which of the sources of communication apprehension have you experienced? In what ways can you reframe those negative thoughts to turn anxiety upside down?

- Were you surprised by any of the common myths? Why?

- What is your strategy for reducing communication apprehension? How might you use a calendar or planner to set yourself up for success?

Key Terms

Communication Apprehension

Self-fulfilling Prophecy

Reference

McCroskey, J. C. (1982). Oral Communication Apprehension: A Reconceptualization. Communication Yearbook, 136–170.