Multimodal Composition: Overview

“All media work us over completely. They are so pervasive in their personal, political, economic, aesthetic, psychological, moral, ethical, and social consequences that they leave no part of us untouched, unaffected, unaltered.”

— Marshall McLuhan, The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects

Technology, the noted philosopher and communications theorist Marshall McLuhan explains, is and has always been an extension of ourselves. Just as the wheel extended our own range of physical movement, your smartphone and the social media programs that you use have become an extension of yourself. We are able to communicate on a scale that would have been unimaginable only a few decades prior, and this expansion has brought with it great power as well as great risks. As the chapter on personal essays notes, you are part of a generation that is communicating more than ever before in recorded history–even if the form of that communication has extended beyond the medium of paper itself. The words that you author and the digital content that you create and share can be seen by an almost infinite number of audiences and can endure more or less permanently once the post or send button has been submitted. You can post content that can inspire millions or, in a weak moment, you may share something that can cost you friends or perhaps a career, days or even years after the fact.

Often, our move into an evermore digital existence is greeted with the worry that our writing and intellectual habits are being forced into a state of decline. This is an understandable concern as informal writing conventions continue to creep into professional spaces under the twin forces of social media slang and text message vernacular. Writing can feel like an outdated art under siege from all corners with no hope for respite ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

However, like the assumption that no one reads or writes any longer, the idea that writing is in a state of essential decline is an oversimplification. Cutting against the grain, linguist Gretchen McCulloch has argued that our writing has actually become far more empowered with the rise of social media and text message norms. Even the most informal aspects of these worlds, such as bitmojis, popular onomatopoeias (oof, lol), the use of gifs in place of words, or the humble emoticon, have effectively “restore[d] our bodies to our writing” and allowed us to “give a sense of who’s talking and what mood we’re in and when we’re saying things. . . . To be fully ourselves in an online world.” We can now massage meaning within our communications in ways that mimic the presence of the human body (our facial expressions, sounds, physical gestures, etc.), and this has, rather predictably, created a vast range of experimental and new linguistic forms. These communications are indeed far less formal than a professional letter, for example, but that does not necessarily make them less effective or even less nuanced or thoughtful.

What has created trouble is the fact that the borders between these new and old forms of communication have become blurred. Slang and conventions from one space are often deployed in places where they do not belong with disastrous results (e.g., using uncapitalized I’s in a letter to your professor or work supervisor). However, these sorts of communicative mix ups do not ipso facto render new forms of communication themselves less valid in the spaces where they were first engineered. In communications with friends and family, it is often rhetorically more effective to respond with an onomatopoeia and an emoticon when difficult subjects arise.

Traditional writing skills also have their place in this strange world of ours, and we should not lose focus of that either. In many ways, a firm grasp of effective writing conventions and rhetorical awareness about the situation in which one is composing have become more valuable than ever before. The rate of technological change is not receding. It is accelerating, and in this shifting world, one must be develop a flexible toolkit to be a successful communicator across an everchanging sea of technologies, audiences, and objectives. In other words, you should strive to become a Swiss Army knife as a writer so that you can successfully compose in the many writing environments that you will find yourself over the course of your personal and professional life. With some luck, this chapter will offer some guidance to make the most of life as a writer and, by extension, content creator in the twenty-first century.

Is the Medium the Message? Watch This Discussion of Marhsall McLuhan’s Idea by MIT Media Lab and decide for yourself.

What Are Multimodal Texts?

Read through the following section on multimodality by Jackie Hoermann-Elliott and Kathy Quesenbury and consider how a multimodal text’s rhetorical situation impacts the choices that go into producing it.

- Use two or more of the five primary communication modes (aural, gestural, linguistic, spatial, and visual).

- Understand how media differ from the communication modes.

First, what is multimodality? Multimodality refers to the five primary modes or ways by which we communicate: aural, gestural, linguistic, spatial, and visual. Think of it this way: If you were composing a message on a social-media platform like Twitter or Instagram, instead of “relying only on alphabetic letters, [you would] include voice messages, images, photographs, music, emoticons, web links, and other . . . multimodal elements to make [your] points” (Ball and Loewe 311). The reference to “alphabetic letters” refers to linguistic communication modes, while the other options draw primarily on visual and aural modes. The key point here is that you would very likely use several communication modes in your post, not just because you can on those platforms but because the combination suits your audience, purpose, and context (i.e., the rhetorical situation).

All communication is multimodal. In this textbook, for example, we communicate with you via words on a page or screen; our modes are linguistic and visual. On the other hand, you may be listening to these words, which we would describe as an aural-linguistic mode. Most communication also includes spatial modes that communicate meaning: On the page or screen, for example, letters are grouped together as words, with space between them; paragraphs are separated in ways that enhance communication, too, along with section headers and titles. In face-to-face interactions or on Zoom, we would speak these words aloud but also add gestures that communicate additional information or cues; such an interaction combines aural, linguistic, and gestural modes.

Multimodality an important skill for your genre toolbox. By choosing the mode(s) best suited to your rhetorical situation, you improve your chances of communicating persuasively and effectively. Being able to choose and mix modes makes you a more skillful communicator. In the advertisement genre, for example, you may be familiar with television ads calling on you, the viewer, to help save abandoned or abused animals. What kind of music typically accompanies the visual and alphabetic elements of such an ad? Sad music. Would these ads work if the music was happy and upbeat? Remember that we have expectations about genres; we expect the music and images in such an ad to evoke sad emotions. In these ads, sound/music, images, and words work together to communicate a message.

Modes and media are different but related concepts. A medium is a singular material or interface through which we communicate a message or messages. Examples of media (the plural of medium) include newspapers, paintings, social-media apps, Zoom, or even your course learning management system. In a sense, media are the materials that lie between the communicator and the communication. A mode, on the other hand, refers to the channels or resources through which media are sent. For example, have you ever seen words or images etched in chalk on a sidewalk? The sidewalk and the chalk are the media; the words and images used communicate the creator’s message through the visual and linguistic modes. In the case of this textbook, the medium is the computer screen; the mode is visual and linguistic (and possibly aural, if you’re using a screen reader or reading aloud).

What’s it like to consider the modes of your composition? Elsewhere in this chapter, we discuss genres that, when considered as written compositions, employ at least two modes (visual and linguistic). Other multimodal possibilities for getting your points across include infographics, photographs, charts and diagrams, slideshows, presentations, podcasts, animation, videos, and so much more. You can use these multimodal genres to supplement your written, “alphacentric” essays, or expand them into new compositions on their own.

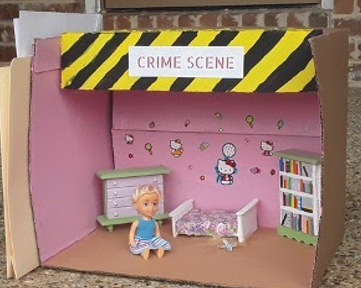

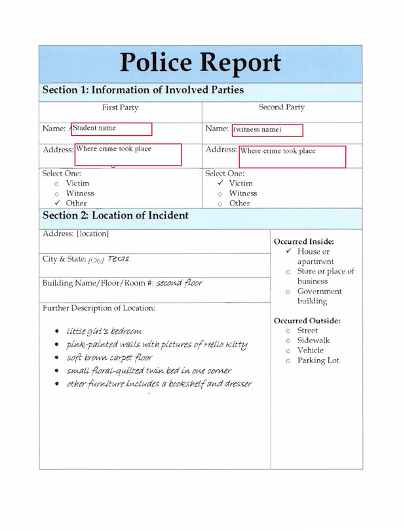

For example, in “The Scissors Incident,” a crafted project featured in the 2020-2021 FYC eReader, the student multimodality transformed a narrative written earlier in the semester. For a remix project later in the course, she pondered ways to present her project in more than two modes. One aspect of the resulting project was a diorama she made of a “crime scene.” What three modes can you identify in a photograph of her project?

When the student presented this project, she used the premise that her “audience” of classmates were investigators attending a “crime” update. First, she provided her audience with a police report documenting the crime, then she talked to them as if she were the chief investigator. Her presentation was aural, linguistic, visual, spatial, and gestural. The diorama is visual, linguistic, and spatial in its use of modes, and so were the handouts. The entire project exemplifies multimodal composing as a practice, a skill you use every time you communicate.

Let’s review. First, modes are the primary ways we communicate—aural, visual, linguistic, spatial, and gestural. Second, all communication is multimodal; that is, all communication combines at least two modes in order to deliver or create meaning. Third, by understanding the modes best suited to your audience, purpose, and situation, you can communicate persuasively and effectively. These factors are why multimodal composing is such a valuable skill to employ across genres.

Attribution on the Web

Sometimes, the web can feel a bit like the Wild West, but as Jude Miller, Amanda Haruch, Samantha Kennedy, and Amy Woodworth note in the following section, careful consideration needs to go into deciding how to use and provide attribution for information on the web.

Key Concepts

- Web-based genres (websites, blogs, etc.) tend to use different citation methods than what’s typically used for a project in a class (e.g. APA, MLA, etc.)

- Attribution–giving credit to the original source when we borrow information–remains necessary in web-based genres

- When composing in web-based genres it remains necessary to be consistent with how we’re giving attribution for borrowed information

- It remains necessary to follow the genre conventions for attribution in the given web genre we’re composing in.

Writing involves an ethical dimension, and an important aspect to considering the ethical dimensions of writing involves following proper attribution protocol when we’re borrowing information from elsewhere. Equally, while we might be familiar with one or two particular citation methods–like APA, MLA, or Chicago–it’s useful to note that the way we’re citing information is dependent on our audience’s expectations and what’s appropriate for the genre we’re writing in. On some level, we’re all already aware of this, since some classes require us to cite things in MLA, while others require APA or Chicago or something else.

Following a set of attribution protocol for any given writing project, then, requires us to understand what the appropriate citation conventions are for the genre we’re working in. Oftentimes, when we’re writing something for a class we’re in, the genre we’re writing in is “College Essay,” or, more accurately, it’s probably a sub-genre of the larger genre of “College Essay”–say “Research Paper,” “Literature Review,” “Lab Report,” etc. And depending on the subject that the class is in, we would typically use a method of citation common to a class in that discipline.

While the way that we attribute borrowed information changes depending on the genre we’re working in or the rhetorical situation itself, what’s important to keep in mind is that we must always attribute any borrowed information to the original author–this includes things that are directly quoted as well as those that are paraphrased. Equally, it includes text as well as multimodal information (like images or videos).

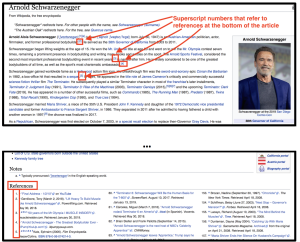

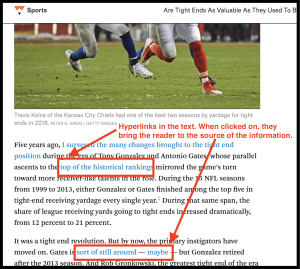

While we might have a lot of experience using a citation method like APA or MLA, we may find ourselves increasingly working in online genres–like websites or blogs for example. As we’re likely aware, when we’re reading something online–like a piece of online journalism or a Wikipedia article–we typically won’t see things cited in the manner we use in our classes, which, depending on the citation method we’re using, often involves an in-text citation that refers the reader to a references section at the end of the work. Equally, not all websites cite things in the same way. For example, Wikipedia (see example) uses endnotes–superscript numbers that point the reader to a citation for a reference at the bottom of the article– while some sources of online journalism (see example) link out to the sources they’re referencing by attaching those sources as hyperlinks that are connected to words in the text.

How to Locate and Use Digital Resources Responsibly

Before delving into the nuances of this topic, please take a moment to watch this introduction to copyright and fair use best practices for images, videos, and audio from the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s DesignLab

The following overview comes from the George A. Smathers Libraries at the University of Florida. This resource not only explains how and to what extent copyright applies, but it also offers a number of resources that you can use to find digital content that exists in the public domain or under a Creative Commons license. An understanding of copyright law and fair use is essential in our digital world, but so too is a working knowledge of where to find usable content. This section represents a treasure trove of resources on both of these important fronts.

What is copyright?

Copyright law reserves rights for creators (and often their employers) to reproduce, share, adapt, and perform what they create.

What does copyright protect?

Copyright applies to tangible materials that have even the tiniest bit of creativity. Art works, written documents, and sound recordings are protected because they are original and can be physically copied or shared. Facts are not protected because they are not original; ideas are not protected because they are not tangible.

In the Weeds: U.S. Copyright Laws

Below is a list of major copyright legislation in the United States with links to the full text.

-

Full text of the Copyright Act, enacted in 1976, which is the primary copyright law in the United States.

-

Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)

A summary of the amendments made to the Copyright Act by the DMCA. The primary change affected by the DMCA is the prohibition of circumvention of technological protection measures and exemptions to this prohibition. -

Technology, Education, and Copyright Harmonization Act (TEACH Act)

Amended section 110 of the Copyright Act to allow limited performance and display of copyrighted items for distance education. -

Made changes to music licensing and protections for pre-1972 sound recordings

The Rights of Copyright Holders

The Copyright Act grants creators protection in their works by bestowing upon them a bundle of exclusive rights with respect to their works:

- The right to reproduce/copy the work

- The right to prepare derivative works (e.g. translations)

- The right to distribute copies of the work by sale or lease or other transfer of ownership

- The right to publicly perform the work

- The right to publicly display the work

- The right to perform audio works publicly by digital means

Copyright protection is automatic and begins the moment any “original work of authorship is fixed in a tangible medium of expression.” Copyright protection does not require any form of copyright notice or registration with the U.S. Copyright Office, although affixing a notice and registering a work enhances protection of the owner’s rights.

What is Protected by Copyright?

Not all types of works are entitled to copyright protection. See the (nonexhaustive) table below:

|

Copyrightable Works |

Non-Copyrightable Works |

| Literary Works | Works not fixed in a tangible form (e.g. ideas) |

| Musical works (including accompanying lyrics) | Short phrases, slogans, commercial symbols/colors (however, these may be protected by trademark law) |

| Dramatic works (including accompanying music) | Ideas, procedures, methods, systems, processes, concepts, principles, discoveries, or devices, as distinguished from a description, explanation, or illustration |

| Choreographic works and pantomimes (must be fixed in a tangible form, e.g. recorded or notated) | Works consisting entirely of common data (e.g. calendar, government weights/measures charts) or entirely of facts (although creative assembly of facts can be subject to copyright, the facts themselves cannot) |

| Pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works | Spontaneous speeches that have not been formally fixed into a tangible form |

| Motion pictures and other A/V works | Spontaneous musical or choreographic works |

| Sound recordings | Federal government documents (mostly) |

| Architectural plans | |

| Computer programs |

(adapted in part from the U.S. Copyright Office “Copyright Basics” circular)

How Long Does Copyright Protection Last?

Copyright protection does not last forever. For new works created in the United States, protection begins with creation of the work and lasts 70 years after the date of creation. At that time, the work passes into the public domain, meaning it may be legally shared, copied, and adapted without permission. For older works created in the United States, cessation of copyright protection and passage into the public domain depends on a variety of factors. See the Cornell Public Domain Chart or the Public Domain tab of this guide for more information.

What is Fair Use?

Section 107 of the United States Copyright Act lists four factors to help judges determine, and therefore to help you predict, when content usage may be considered “fair use.”

The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit, educational purposes and whether the use is transformative, that is the use is for a new audience or a new purpose.

The nature of the copyrighted work. Use of a purely factual work is more likely to be considered fair use than use of someone’s creative work.

The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyright protected work as a whole.There are no set page counts or percentages that define the boundaries of fair use. Use of an entire work can be fair use if it is necessary to carry out a very transformational purpose that has no effect upon the market for the original.

The effect of the use on the potential market for or value of the copyright protected work. This factor looks at whether the nature of the use competes with or diminishes the potential market for the form of use that the copyright holder is already employing.

To assist you in conducting your own fair uses analyses, you can use this Fair Use Checklist.

Fair Use Myths

What I am doing is educational, therefore it is fair use.

Just because your use is for a non-profit educational purpose does not automatically give you permission to copy and distribute other people’s work. ‘Educational purpose’ is only one of the four factors relating to a fair use determination. To decide whether a use is a fair use, the effect on the market, the amount used, and the nature of the work must also be taken into consideration.

I am not making any money from the use, therefore it is fair use.

Effect on the market is only one of the four factors relating to a fair use determination. Whether or not you are making money does not matter so much as whether you are replacing the market for the item, for example if people can view your item instead of having to purchase it. To decide whether it’s a fair use, the effect on the market must be taken into consideration along with the other three factors: amount used, the purpose of the use, and the nature of the work.

If I am making money from the use, it cannot be a fair use.

Even commercial uses can be fair use. It’s all about the balance and weighing the four factors to come to a conclusion. If other factors are in favor of a fair use, it may balance the fact that you intend to make money from the use.

So long as I am not using something that is entertaining, it can be fair use.

Copyright is concerned with originality, not quality. Whether it’s high artistry or low budget B movies, anything that is an original and tangible creative expression receives copyright protection according to U.S. law.

As long as I provide proper attribution for a use, I do not need to seek permission.

Attribution is a matter of ethics and responsibility, but it has no bearing on a fair use assessment. To determine whether you have a fair use, you will need to go through the four factors assessment according to your intended use.

So long as I only use a screenshot or a still from a film it will always be fair use.

Even the smallest bit of a work including screenshots or stills can have copyright. There is still copyright in small portions of a work. You must make your own fair use assessment of the little bit you want to use. It may be a fair use to use a screenshot or still – but you still need to look at each use in light of all four factors and the overarching purpose of fair use.

I only copied 10% so it must be fair use.

There are no “bright line” rules for fair use; guidelines are not the law. A small amount could be the heart of the work and not fair use. There are no numeric rules, and that’s a good thing–you’ll want always to have the right to exercise judgment on what amount/which content you might need to use within your work.

If it is fair use in the classroom, then it must be fair use to use it online.

There are different facts to consider when copying materials for online use, particularly when considering use of media or other visual works online. A fair use analysis must be conducted for online use same as for classroom use.

Compiled from University of Michigan, Case Western Reserve University and the Center for Social Media at American University

In the Weeds: More on Fair Use

-

Fair Use – Stanford Copyright & Fair Use

From the NOLO Press book Getting Permission, overview of fair use. -

Developed by Kenneth Crews and Dwayne Buttler, one of the first Fair Use checklists to enter the field. The checklist is a tool for helping one conduct fair use analysis but does not provide a definitive conclusion.

-

Fair Use of Copyrighted Materials

From the University of Texas “Crash Course on Copyright,” excellent overview of fair use law. -

Visual explanation of fair use from BYU.

-

Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Academic and Research Libraries

From the Association of Research Libraries, a description of 8 common library practices where fair use can be successfully employed, with certain enhancements and limitations.

Public Domain Overview

The basics

When you take a photograph, write a poem, or even jot down a to do list, your work is automatically protected under U.S. Copyright Law, and people will usually need to ask your permission to share your creation online, translate it into new languages, or perform it in front of an audience. Well into the future, the copyright will expire, as it already has for millions of works of art, music, film, and literature. These materials have become part of the “public domain,” collections that are legally available for anyone to reuse or remix.

An item might be in the public domain in the U.S. if:

- It was published before 1926. (Note that published in this context means “copied and distributed beyond a small group of people.” This means flyers, brochures, etc. are usually considered “published.”)

- It was published from 1926-1977 but there is no © symbol or statement printed on the item.

- It was created before 1901 by an anonymous creator but never published.

- The item was unpublished (e.g., a family snapshot) and the creator died before 1951.

- The item was created by the Federal government or Florida government employees.

It’s nice to share

Anyone who owns a copyright may also share their work as part of the public domain, meaning others may legally use it without permission. Usually this is done by labeling with a “CC0” license; this and some other licenses allow for almost any use, commercial or noncommercial.

Do no harm

It’s important to remember that just because it is legal to use something, this doesn’t always make it right. There’s a complex history behind every cultural work, and even if the copyright has expired sharing the material could invade someone’s privacy or appropriate aspects of someone else’s culture. Many works in the public domain were created in the 19th or early 20th centuries and contain racist imagery that continues to be harmful and potentially traumatic today.

Additional Resources About the Public Domain

Public Domain—Images

- American Memory: Photos and Prints—From the Library of Congress, nearly 70 collections of photos, much of which is in the public domain, but be sure to check for a copyright statement.

- NASA Images—NASA hosts several image collections, including photographs taken by astronauts and images from the Hubble Space Telescope. As works created by the federal government, they are in the public domain.

- PD Photo—Nice collection of royalty free photos.

- Best Places to Find Free High-Res Images—This website has compiled a comprehensive list of online resources for high-res public domain and Creative Commons licensed images for use on web pages and other resources.

Public Domain—Audio

Very few sound recordings are in the public domain in the United States; in fact, most sound recordings will not enter the public domain until February 2067! However, there are many sound recordings that have been licensed with Creative Commons. See the Creative Commons page for resources.

- Library of Congress National Jukebox— A Large and growing collection of spoken word and musical works mostly found in the public domain.

- Musopen—MP3 recordings of public domain music.

- Choral Public Domain Library

- Internet archive — Audio — Some recordings are public domain)

- Mutopia — Public domain or Creative Commons licensed music.

Public Domain—Video

As with audio, determining whether video content has entered the public domain can be complicated. We recommend that you contact the Library for copyright advice if the work does not include any indication of copyright status.

There are many collections containing public domain video content:

Creative Commons Licenses Explained

The Creative Commons organization was founded in 2001 as a means of permitting creators to license their work for public use under conditions they specify. Although not an alternative to copyright and not an indication that a work is part of the public domain, Creative Commons licenses permit the holders of copyright to define more clearly, than perhaps modern copyright law interpretation allows, how their works may be used and give users of copyrighted works greater creative freedom when they know, without question, how copyrighted works can be incorporated into new creations.

Locating Creative Commons Licensed Content

Below are links for locating images, music, and other resources licensed through Creative Commons.

-

Search form offering convenient access to search for Creative Commons licensed content provided by other independent organizations, including Google Images, Flickr, and YouTube.

- PhotoPin

- This image search engine returns both Creative Commons and non-Creative Commons images. When you download any image, you can also download the necessary HTML to appropriately attribute the image to its creator.

- CC Mixter

-

- A community music remixing site featuring remixes and samples licensed under Creative Commons licenses. Music on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons license. You are free to download and sample from music on this site and share the results.

-

- Jamendo

-

- Community of free, legal and unlimited music published under Creative Commons licenses.

-

- Pixabay

- Collects images under a Creative Commons CC0 License.

- Wikimedia Commons

- Features millions of free-to-use images, audio files, and videos.

- Flickr

- After you initiate a search, click the “any license” option, and you can modify the license-type of your search results.

- Unsplash

- the Unsplash license grants users an irrevocable, nonexclusive, worldwide copyright license to download, copy, modify, distribute, perform, and use photos from Unsplash for free, with or without attribution

- Advanced Google Searches

- As with Flickr, you can modify the types of licenses that appear in your image and video searches. Click on “Tools,” then “Usage Rights” to open the Creative Commons license search filter

- YouTube

- After you search a topic, you can select the option to only have content with Creative Commons licenses appear in your search results.

Watch this brief history of Creative Commons licensing, courtesy of Wilson College’s John Stewart Memorial Library

Recapping the Main Ideas Behind Attribution on the Web

Anytime we’re citing things online, we must:

- Give full credit to the original source, as we would anytime we are citing anything in any format

- Follow the appropriate conventions for the genre and the rhetorical situation.

- Be consistent about how we’re citing things

- Make sure that the content is accessible to a variety of audiences

Sources Used to Create This Chapter

The chapter’s content on multimodality has been adapted from OER Material from “Multimodality” in Writing as Inquiry and Argumentation by Jackie Hoermann-Elliott and Kathy Quesenbury. This work has been shared under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The content on attribution in digital environments has been adapted from “Attribution on the Web” in College Comp II by Jude Miller, Amanda Haruch, Samantha Kennedy, and Amy Woodworth. This work has been shared under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The content on digital copyright, fair use, the public domain, and Creative Commons licenses comes from the “Copyright on Campus” collection from the George A. Smathers Libraries at the University of Florida. This work has been shared under the following license: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0)

Media Resources

Any media resources not documented here were part of the original chapter from which this section has been adapted.

Videos

“Copyright and Fair Use for Images, Videos, and Audio – Basics.” The University of Wisconsin–Madison’s DesignLab. This work has been shared under the following license: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

“How the Medium Shapes the Message.” YouTube. Uploaded by MIT Media Lab. This work has been shared under the following license: Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

“The Story of Creative Commons.” YouTube. Uploaded by Wilson College’s John Stewart Memorial Library. This work has been shared under the following license: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Images

- Digital technology photo, by Marvin Meyer on Unsplash

Works Referenced

McCullough, Gretchen. Because Internet: Understanding the New Rules of Language. Riverhead Books, 2019.