Search Strategies

Some of your college instructors may have grown up in a very different information environment, using different research tools to find the information they needed.

Instead of electronic databases, they may have used indexes like The Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature to identify promising articles and then located the full text of the articles in large bound volumes of print journals in library stacks or on microfilm.

To find print books, they may have used a card catalog. Card catalogs allowed library patrons to search for print books in one of three ways—alphabetically by title, alphabetically by author, and by the handful of subject headings that were assigned to books based on their content. Browsing physical shelves, browsing subject-related print journals and indexes, and following citations found in the references of books and articles were all essential research strategies. To some degree these strategies remain essential to conducting research, though the tools have changed dramatically over the last couple of decades and research behaviors have evolved accordingly.

The electronic indexes of today are much more powerful research tools. Today’s library databases allow you do full text searches of millions of articles at once. Ebooks have made the large print collection optional for many kinds of research. Has something been lost in this change from print to electronic collections? Perhaps so. Browsing physical books and scholarly journals was once a terrific way to come up with interesting research questions and make connections between different concepts, different experiments, and theories, and this strategy is far less common today. After all, why browse library shelves for long hours for information when you can quickly find what you need to answer a research question with just a few thoughtful keywords? In that sense the improvements to the accessibility and searchability of information may actually put today’s researchers at a bit of a disadvantage.

Making conscious choices about where you do your research requires an understanding of what tools are available and when each tool is best suited to addressing a particular research need. For example, as we discovered earlier, peer-reviewed scholarly literature is the gold standard for many types of research. A simple vanilla Google search is unlikely to connect you with scholarly literature, so it would be a poor choice of search tool for finding scholarly articles. The Library Catalog is also a poor place to locate peer reviewed scholarly literature, though it might be ideal for finding books and films. Let’s briefly look at the most popular research tools, along with the kinds of content you can expect to find in each.

Library Catalogs

Library catalogs allow researchers to search the local print collection at their library.

Typically the catalog is a useful way to find print books, though eBooks, microform, films, and special collections records are also likely to be included. A library catalog allows users to search by author, title, journal title, subject, and often by series, ISBN/ISSN, publisher, and call number as well. A catalog may search all these fields at once, or only the fields you have selected to search. Note that when doing searches in library catalogs, you are usually not searching the full text of the books and other materials that are indexed by the catalog.

As we said earlier, we are searching though the subject headings each item in the catalog has been assigned, along with a few other basic pieces of information about the book. Book records in catalogs are thus quite sparse compared to the more extensive indexing found in article databases. The subject headings assigned to books come from a “controlled vocabulary” that ensures the same language and terminology is used to describe similar topics.

So for example, if your subject search is giving you poor results, you may not be using the correct “controlled vocabulary” to describe your topic.

Tip: A subject search on “feline” is likely to give you very few results, because books about felines use the controlled vocabulary term “cats.” One you have found an item on your topic, you can look at the item’s record and see the subject headings that the item has been assigned. You can then click on the subject heading to see other items in the catalog that has been assigned that same subject heading.

Library Databases

You will often hear about databases in academic libraries.

Library databases are an important resource for researchers, both student and professional, and understanding how they work will make your library research in the future easier and more productive. So what is a library database? A database is just a searchable collection of information. We use different kinds of databases every day. Apple’s ITunes is a database of songs to buy. Amazon.com is a huge database of products for sale. Even your cellphone includes a database of family and friends’ names and phone numbers. Library databases are collections of magazine and newspaper articles, book chapters, conference proceedings, and other kinds of digitized research material. Different library databases contain different kinds of content.

Most databases only include articles for a particular subject area. An example of a subject-specific database is the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL,) which contains the full text to over 600 different nursing and allied health related journals. Naturally, the CINAHL database would be a poor place to find English Literature or History articles, but would be excellent for finding high-quality articles for nursing or other health-related areas like nutrition.

Some databases contain only certain formats of material. ProQuest Newsstand contains hundreds of reputable national and international newspapers, but only newspapers—no journals, no book chapters. Films on Demand contains only videos. ACLS Humanities E-Book contains only ebooks. So be aware not only of a database’s subject area, but also of the kinds of material formats it contains.

Finally, a few databases are multi-disciplinary. This means that a single database might cover many different subject areas. These large multi-disciplinary databases are often the best, first stop when doing library research. ProQuest Research Library is an example of a multi-disciplinary database. You’ll find articles in ProQuest Research Library on a wide variety of topics, from political science and psychology to English literature and education. Because databases contain such a huge amount of content, you will want to think about ways to weed unhelpful items out of your search results.

Before you begin a database search, select any limiters that you’d like to use.

Limiters filter out content that you know you don’t need. So for example, do you need articles from only a particular date range? There’s a limiter for that, which will weed out articles outside that particular range. Only interested in scholarly articles? Mark off that limiter, and all but scholarly articles will be weeded out of your search. While different databases may look different, the tools are all generally pretty similar. One thing to note is that not every database or database record is available in full text. A database might contain hundreds or even thousands of different full text journals, but may also include article records where the full text is not available. These abstract-only article records may not be immediately useful to you, but most libraries have an interlibrary loan service that can quickly request the full text of the articles for you. If you have questions about using interlibrary loan and accessing items beyond your library’s collections, speak with a librarian.

Tip: Databases typically focus on particular areas of study, such as communications or engineering, and they can be enormously helpful for finding discipline-specific information relevant to your topic. But ask yourself if your research topic has a multidisciplinary angle and choose your databases accordingly. For example, if you are researching bullying in schools, you may want to do your searching in databases from a number of database categories, as the topic touches on a number of literatures: Education, Sociology, Child Development & Family Relations, etc. Think about the whole range of places where published research on your topic is likely to appear.

Discovery Services

Library discovery services are the newest of the tools available to student researchers.

Discovery services allow a user to conduct a search across multiple collections at once. Whether you need books from your library’s physical collection, a piece of microfilm, a newspaper article from the 1800’s, or a scholarly article just published in a wellregarded journal, a discovery service will provide relevant search results. It has long been a dream of libraries to provide their users with a single search tool that searches across their entire collections, both print and electronic. Discovery services represent their current best effort at creating such a tool, allowing users to search the full contents of a library’s local print collection and a majority of the database content in a single search.

Discovery services are not without issues that you need to know about. While the content of most databases subscribed to at your local library may appear in its discovery service search results, the content of some databases will not. Determining which databases are included in your local discovery service and which are not can be difficult. Another shortcoming of discovery services is the lack of discipline or database-specific search tools. For example, consider the nursing database CINAHL. While articles located in CINAHL may appear in keyword searches in your local discovery service, you will not have access to CINAHL’s special subject heading controlled vocabulary tool unless you conduct your search within the database itself. Or a student researcher interested in finding content on certain kinds of businesses and industries may want to search for information using NAICS (North American Industry Classification System) codes. These six digit codes can be searched in select business databases, but a discovery service is unlikely to provide that same functionality, even if the articles and reports themselves will appear in discovery service search results.

Tip: For research projects where you are asked to have a mix of books and articles as references, discovery services can be ideal places to begin your research. Discovery services can also be helpful when your research topic is multidisciplinary in nature (i.e., it touches on the literature from several fields of study,) as it draws in search results from databases in a number of different fields in a single search.

Google is a terrific tool for locating information across the more than 30 Trillion web pages it indexes.

What can you expect to find with a Google search, and what is likely to be excluded? While Google indexes and connects you to a massive amount of information, it does not necessarily own the content it indexes. Books and scholarly journals are typically not free, and so Google is a poor way to find these types of sources. More exactly, Google may lead to you useful book and article citations, but is unlikely to give you full access to those books or articles. Still, Google can be useful for gaining a global understanding of an unfamiliar topic, and can connect you to useful sources such as professional organizations and federal documents.

TIP: Vanilla Google searches can be made more powerful by taking advantage of a few useful tricks. For example, you may want to only search a particular domain or website. Do so by adding “site:” before or after your search terms.

For example:site:.edu or site:.gov

You can also have Google provide you with only certain types of results.

For example, if you only want to see PowerPoint presentations or PDFs in your search results, try:Filetype:pdf or filetype:pptx

Google Scholar

Google Scholar indexes peer-reviewed articles in much the same way that vanilla Google indexes web pages.

Unfortunately, Google Scholar does not own the content of the articles it indexes. So while a Google Scholar search may yield genuinely useful, high quality results, the full text of the articles may not be available. Note, though, that there are two major exceptions: Content owned by your library If the article in your Google Scholar search results is owned by your library, you may have access to it in your Google Scholar results. Click on “settings” and then “library links” to see if your campus is set up to work with Google Scholar, or just check with your local librarians. A “Google Scholar” link that automatically connects you to content your library owns may be available on your library’s website. • Open Access Journal articles Because of the high cost of peer-reviewed journal subscriptions, a number of journal publishers have switched to an open access publishing model. In addition, many universities have adopted open access mandates, requiring that their researchers make copies of their research freely available in institutional repositories. Accessing these open-access articles requires no special fees or affiliations.

TIP: The option to do an “advanced search” in Google Scholar currently only appears after an initial search. Once you have done a search, look for the downward arrow on the right side of the screen to select “advanced search.” From here you can search for articles by title, author, or publication.

Understanding the Library in Reference to Research Assignments

Students often encounter a checklist of different publication format requirements when they receive their first major research assignment. They may be asked to use a certain number of books as sources, or a certain number of scholarly journal articles; they may be asked to use several different formats for the same paper.

Before starting on a research assignment, students may not have thought much about these different kinds of sources and why each exists. Some formats will be relevant to one research question but not others. Which are likely to be most useful to you will depend on both your assignment requirements and the nature of your research question.

Let’s use the scenario below to look at the major formats you are likely to encounter.

Scenario

Harry is feeling overwhelmed by one of his class assignments. Harry would have been happy if the assignment was to write a traditional research paper, but his professor has asked the class to solve a real life problem. The professor has asked the class to imagine a small city undergoing a natural disaster such as a flood or a tornado. Each group in the class is required to plan a hypothetical information command center for this city. The professor explains that the government needs to obtain accurate, up-to-date information on the scope of the damage and injuries sustained due to the disaster. This information is vital for the city to be able to provide adequate emergency and medical assistance to its citizens. Harry can see that this is an important function for any city in the midst of a crisis but he is not sure about where to get reliable information to help him construct a plan for the city.

Harry and his classmates do some brainstorming and decide to approach this assignment as if they were actually producing a research paper. Their first step will be to research recent disasters. They reason that this will provide some information about the way some cities have gathered information during disasters. If an information gathering strategy worked for other cities, it will work for their hypothetical city. There certainly have been a lot of natural disasters recently, so it shouldn’t be too hard to find some information. Super Storm Sandy and Hurricane Irene are two recent events that immediately come to mind. The group starts to research Super Storm Sandy with Google and Wikipedia.

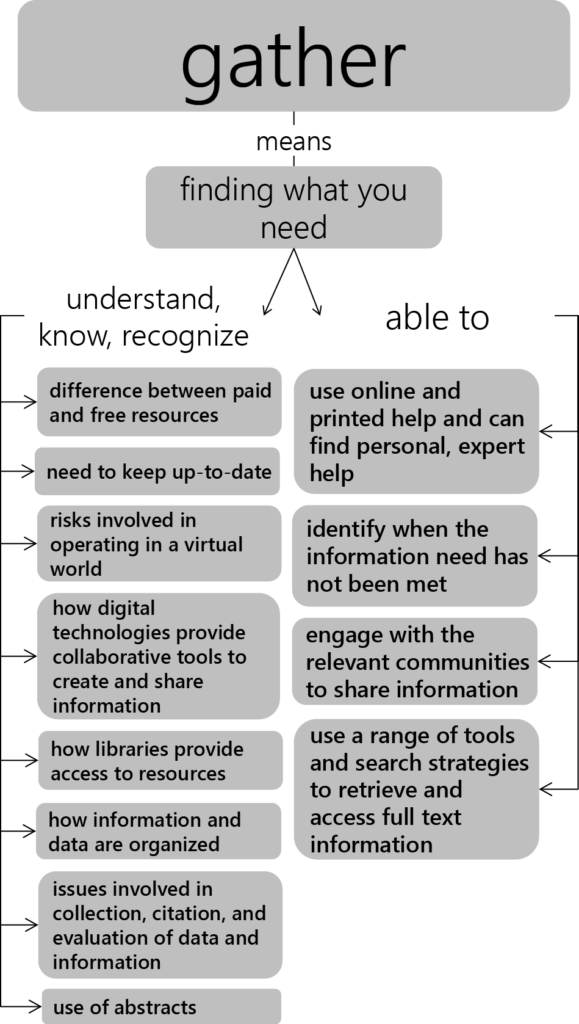

Harry and his group members need to gather information that will help them complete this assignment. To do so, they will use the “Gather” pillar from the Seven Pillars of Information Literacy Model.

The Gather pillar states that the information literate individual understands

- How information and data are organized

- How libraries provide access to resources

- How digital technologies provide collaborative tools to create and share information

- The issues involved in collection of new data

- The different elements of a citation

- The use of abstracts

- The need to keep up to date

- The difference between free and paid resources

- The risks involved in operating in a virtual world

- The importance of appraising and evaluating search results

And they are able to

- Use a range of retrieval tools and resources effectively

- Construct complex searches appropriate to different digital and print resources

- Access full text information, both print and digital, read and download online material and data

- Use appropriate techniques to collect new data

- Keep up to date with new information

- Engage with their community to share information

- Identify when the information need has not been met

- Use online and printed help and can find personal, expert help

Information Formats and the Internet

Traditionally, information has been organized in different formats, usually as a result of the time it took to gather and publish the information. For example, the purpose of news reporting is to inform the public about the basic facts of an event. This information needs to be disseminated quickly, so it is published daily in print, online, on broadcast television, and radio media. More in-depth treatment of information takes longer to research, write, and publish and traditionally was published in scholarly journals and books.

Today, information is still published in traditional formats as well as in newly evolving formats on the Internet. These new information formats are loosely defined as Web 2.0 formats and can include electronic journals, books, news websites, blogs, Twitter, Facebook, and location postings. The coexistence of all of these information formats is messy and chaotic. The process for finding relevant information is not always clear.

One way to make some sense out of the current information universe is to thoroughly understand traditional information formats. We can then understand the concepts inherent in the information formats found online. There are some direct correlations such as books and journal articles, but there are also some newer formats like tweets that didn’t exist until recently.

Let’s look at the news industry. Many traditional newspapers are shutting down, and those that remain are retrenching. While there are many reasons for this, one of the major trends has been the rise of the Internet. In the United States, more than 50 per cent of the population reads the news online.

Indeed, online news sites provide a different and, some might argue, a more relevant experience for the reader. They offer video and sound, up-to-the-minute updates on breaking news, and the ability to interact with the content by posting comments. Another important feature of online news is that search engines can deliver content from the site in response to a query. In other words, readers don’t have to visit a site such as the New York Times in order to read its content.

This has both positive and negative consequences. The positive consequence is that readers can quickly and conveniently obtain information from a variety of sources on a topic or event. The negative consequence is that it is more difficult to evaluate the credibility of the sources. The Evaluate chapter in this book provides some good strategies for evaluating information sources.

For Harry and his group, all of this means they will have to research many different kinds of information resources in order to create an effective information command center.

Twitter and Blog Postings

Many of the group’s Google results are Twitter feeds and blog postings. These did not provide a lot of information. After all, a tweet consists of only 140 characters. However, these resources did help Harry’s group by suggesting key people, cities, technologies, and other resources associated with Super Storm Sandy to research. Often a blog posting will provide a link to a longer, more useful resource. The students’ review of blogs and tweets also provided an otherwise unthought-of insight. As Harry and his group were reviewing Twitter feeds posted during Super Storm Sandy, they noted that people were using Twitter to inform their friends and relatives about their whereabouts, their health, and the conditions of their surroundings. Since electricity was not available, most televisions and radios did not work, but mobile technologies like Twitter served as effective communication tools. Once Harry realized this, a Twitter feed was quickly incorporated into his command center’s communication plan.

Newspaper Articles

One of the members of Harry’s group suggested they should consult a newspaper to see what role the newspaper played to help the city understand the destruction caused by the storm. The group chose the New York Times. The New York Times can be accessed online and articles from the day of the storm can be viewed. However, the group found that more useful information was published in the New York Times in the days after the storm. Harry’s initial search of the New York Times for articles containing the phrase super storm Sandy published on October 29, 2012 resulted in some blog postings from reporters and many stories about damage from the storm. But when Harry reentered his search without a date limit, he retrieved articles that analyzed how the region’s municipalities performed during the storm. It takes time to conduct this type of analysis, so looking for information that was published days, weeks, or months after the storm took place was a good strategy.

Many other newspapers can be accessed online or at a local library in microfilm. Microfilm is a film image of the print version of a newspaper. Most libraries hold many years of newspaper issues on microfilm. A microfilm reader is required to view the microfilm version of a document. Libraries that own newspapers on microfilm also provide the microfilm readers.

Primary Sources

Another member of Harry’s group recalled that he had cousins in New York City who experienced Super Storm Sandy firsthand. He offered to interview his cousins about their experiences during the storm. This type of information is known as a primary information or source. Primary sources are accounts from a person or persons who have firsthand knowledge of an event. Speeches, photographs, diaries, autobiographies, and interviews are all primary sources.

In this case, the primary source is still alive and is accessible to Harry’s group. However, some researchers are not so fortunate. If this is the case, primary sources can still be found in a variety of locations and formats. There are many online sites that have created digitized collections of copies of diaries and letters from historical events. It is important to remember that primary sources are not limited to a single format. You may find them in books, journals, newspapers, email, websites, and artwork.

Scholarly Journal Articles

The results of the research that Harry and his group has done are useful, but Harry is concerned that there might be too much focus on Super Storm Sandy. He wants to find more information on crisis and disaster management in general. Harry thinks that there might be general standards or practices that should be incorporated into his group’s plan. Journal articles and books might provide this information.

Harry starts his search for journal articles by using a multidisciplinary database because he is not sure which specific disciplines will cover the information he seeks. He constructs and executes a search query and finds that the abstracts included in the results help him choose several peer-reviewed, or scholarly, articles to read.

Scholarly journal articles usually include an abstract at the beginning of the article. An abstract summarizes the contents of the article. In an abstract, key points as well as conclusions are briefly described. Abstracts are often included in the database record. Researchers find this information helpful when deciding whether or not to retrieve the whole article.

Most of the articles that Harry chooses are available in PDF format from the database, but there are a few articles that look very relevant that don’t have links to a PDF. Harry really wants to read these articles so he decides to try to find out if there is another way to obtain the full text. He consults a librarian who instructs him to look for the title of the journal (not the article) in the online catalog. The catalog record will provide information on whether the journal is available online from another database or if it is available in print.

Journals, and the articles they contain, are often quite expensive. Libraries spend a large part of their collection budget subscribing to journals in both print and online formats. You may have noticed that a Google Scholar search will provide the citation to a journal article but will not link to the full text. This happens because Google does not subscribe to journals. It only searches and retrieves freely available web content. However, libraries do subscribe to journals and have entered into agreements to share their journal and book collections with other libraries. If you are affiliated with a library as a student, staff, or faculty member, you have access to many other libraries’ resources, through a service called interlibrary loan. Do not pay the large sums required to purchase access to articles unless you do not have another way to obtain the material, and you are unable to find a substitute resource that provides the information you need.

There is one more feature Harry found while searching in databases: some offer the option of an alert service. This feature allows Harry to enter the most productive search strings, as well as his email address. When new items are added to the database that fit his search, he receives an alert. Harry found this to be a great way to keep up to date with new articles on his topic without having to initiate a new search.

Books

Next, Harry’s group looks for books on the topic. They search the library’s online catalog using search terms that were successful in their database searches. They find some great titles and head to the library stacks to retrieve them.

Most academic libraries use the Library of Congress classification system to organize their books and other resources. The Library of Congress classification systems divides a library’s collection into 21 classes or categories. A specific letter of the alphabet is assigned to each class. More detailed divisions are accomplished with two and three letter combinations. Book shelves in most academic libraries are marked with a Library of Congress letter-number combination to correspond to the Library of Congress letter-number combination on the spines of library materials. This is often referred to as a call number and it is noted in the catalog record of every physical item on the library shelves.

Harry uses the call numbers to locate some books that he found in the catalog. He is happily surprised to find that there are also some really useful books sitting on the shelf right next to the books he previously identified. This is a handy way to find additional information resources on a topic. It is more efficient to first search the online catalog to locate relevant resources and then search the shelves.

Library of Congress Classification

A General Works — includes encyclopedias, almanacs, indexes

B-BJ Philosophy, Psychology

BL-BX Religion

C History — includes archaeology, genealogy, biography

D History — general and eastern hemisphere

E-F History — America (western hemisphere)

G Geography, Maps, Anthropology, Recreation

H Social Science

J Political Science

K Law (general)

KD Law of the United Kingdom and Ireland

KE Law of Canada

KF Law of the United States

L Education

M Music

N Fine Arts — includes architecture, sculpture, painting, drawing

P-PA General Philosophy and Linguistics, Classical Languages, and Literature

PB-PH Modern European Languages

PG Russian Literature

PJ-PM Languages and Literature of Asia, Africa, Oceania, American Indian Languages, Artificial Languages

PN-PZ General Literature, English and American Literature, Fiction in English, Juvenile Literature

PQ French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese Literature

PT German, Dutch, and Scandinavian Literature

Q Science — includes physical and biological sciences, math, computers

R Medicine — includes health and human sexuality

S Agriculture

T Technology — includes engineering, auto mechanics, photography, home economics

U Military Science

V Naval Science

Z Bibliography, Library Science

Citations

As Harry’s group starts to read and digest all of the information they have gathered, they notice that many articles and books contain references to other articles and books. Even Wikipedia entries contain references. These consist of citations to resources that authors have quoted or paraphrased in their work or have used to research for their publications. Some of these citations look like they would provide great information. But the group is confused. They don’t know if the citation is to a book or an article or something else.

Citations can be confusing. There are many different citation styles and not many hard and fast rules about when to use a particular style. Your professor may indicate which citation style you should use. If not, the general rule of thumb is that the Social Sciences and Education disciplines use APA (American Psychological Association) citation style, while the Humanities and Arts disciplines use MLA (Modern Language Association) or the Chicago style. You can find detailed information about how to format a citation in these styles by consulting the latest Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, for APA citations, the most recent copy of the MLA Handbook, or the current Chicago Manual of Style. You can also get help with MLA citations by referring to the Documentation and MLA Formatting section of this textbook!

However, just knowing what citation style is used doesn’t always clear up the confusion. Each different information format is cited differently. The most common formats that you will encounter are books, chapters in books, journal articles, and websites.

Take a look at the following citations. You can see that there are differences between citation styles. You can also see that each information format contains different elements. When you try to determine whether a citation is for a book, book chapter or journal, think about the elements inherent in each of these formats. For example, a journal article appears in a journal that is published in a volume and issue. If you see volume and issue numbers in the citation, you can assume that the citation is for a journal article. A book chapter is usually written by a different author from the editors of the whole book. A whole book is often the easiest citation to decipher. It contains the fewest elements.

Sharing Information

Harry had a chance to talk with members of some of the other groups in his class about the hunt for information. This was initially done informally before class started, but he wished there was a more formal process, since it was so helpful to all the groups who participated. Harry’s group shared some of what they’d learned, and also found out about some strategies others had used. The students lamented that the professor hadn’t set up some sort of electronic forum where they could share tips and resources, but then decided to do it themselves! They set up a shared folder on Google Drive. It felt a bit strange at first, being collaborative in this way, but it really helped everyone. One group was struggling to find information that met their needs, but between working with a librarian and consulting the wiki, they succeeded with their project.

Conclusion

Harry and his classmates have spent time gathering information to help them create a realistic and accurate crisis command center. They accessed and used online information sources in the form of Twitter feeds and blogs. They used online newspapers and online journal articles. They even gathered some very useful hard copy books. During this process, the students learned about different ways that information is organized including the Library of Congress classification system. Harry was amazed at the wealth of quality information he was able to gather. It took him a while and the process was more complicated than just searching the web, but Harry now feels more confident about acing the assignment. He also feels that he learned more than how to set up a command center. He learned how to engage in academic research!

Exercise: Comparing Search Strategies

Find a newspaper article about a national event, such as the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. Make note of your search strategy.

Next find a newspaper article about a local event, for example, a flood in your area or a local crime or election. Make a note of your search strategy for this search.

Compare the two strategies. How are they alike? How are they different? Which newspaper article was easier to find? Why?

Sources Used to Create This Chapter

The majority of the content for this section has been adapted from the following OER Material:

- Information Literacy Concepts by David Hisle & Katherine Webb, and published under a CC-BY-NC-SA license.

- The Information Literacy User’s Guide by Deborah Bernnard et al., and published under a CC-BY-NC-SA license.